[ Jack Batten / That Ever-loving, Web-footed, Made-in-Canada Dog ]

This article appeared in the March 20, 1965, issue of McLean's, a Canadian magazine that began publishing in 1905, focusing largely on Canadian culture and politics, along with publishing fiction and general-interest articles. It continues to publish to this day.

Jack Batten (b. 1932) is a Canadian lawyer and prolific writer of novels, essays, and reviews on a variety of topics.

It may be possible to quibble with the "made-in-Canada" claim — the English had as much to do with the current breed as the Canadians, if not more — but put that thought aside for the moment and enjoy this delightfully charming encomium to the breed:

The first thing you notice inside Joe and Pollie Loring's house in King, Ont., after you’ve picked yourself up off their rug, is six hundred pounds of dog. The Lorings own four Newfoundland dogs, each weighing about a hundred and fifty pounds and each given to good-natured, leaping, hundred-and-fifty-pound welcomes to the Lorings' visitors. The second thing you notice is children, six of them, all Lorings — Louise, Margaret, Joshua, Caleb, Sarah and Janet, thirteen to five in respective descending order of age. You might also catch a glimpse in there somewhere of a gracefully aging cat named Dolores, a creature, it goes without saying, with resources of survival beyond all imagining. But it's the Newfoundlands that rivet most of your attention.

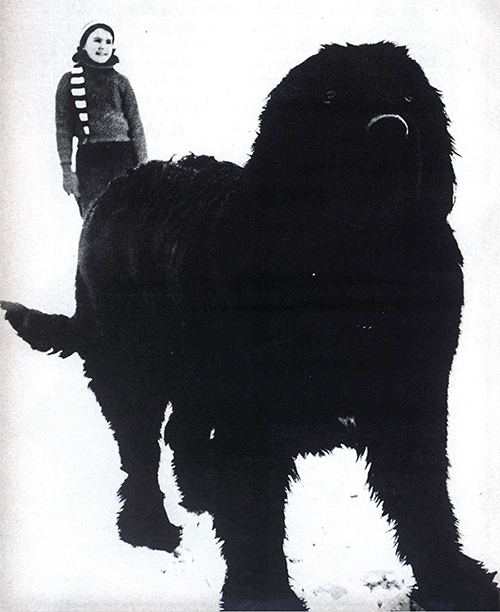

Apart from their impressive bulk — which you can contemplate in its awesome glory in the Lorings’ dog Elbie, who is peering past you from the facing page — Newfoundlands are fascinating for the air of shaggy, embarrassed good humor they give off. They look exactly the way they're shown in those old James Thurber cartoons — just like, for instance, the large resigned mutt that is being carried into a vet’s office by a man grumbling. "Here's a study for you, doctor — he faints." Despite their portly bearing, Newfoundlands manage to move around a house of average proportions such as the Lorings’ with a surprising amount of tact and agility, like canine Sidney Greenstreets. Outside the house, though hardly up to greyhound standards, they can accelerate to a fine rambling speed, and as for jumping, Joe Loring swears one of his dogs can clear six feet from a standing start.

But above all their characteristics — or perhaps as a total of all their characteristics — Newfoundlands, in the Lorings' house or anywhere else, are unavoidably lovable. Personally, I've never had much trouble withstanding the alleged attraction of pet animals, but even I found the Newfoundlands' lumbering charm pretty close to irresistible. Their appeal is almost instant and it's also, apparently, uniquely durable: since my visit to the Lorings, I've discovered that over the last three or four centuries Newfoundlands have been the objects of more selfless — and deserved — human love than almost any of God’s four-legged creatures.

The Lorings, who can be taken in all respects as typical Newfoundland owners, came by their first Newfoundland in 1957. They were looking for a dog that would be affectionate and, as all young North American families stipulate, "good with kids." They picked a Newfoundland named Christopher, and he and the dozen or so of his descendants and successors who have found a home at the Lorings' have met their owners' stipulation with single-minded devotion, though some of them have had their patience with children put to fire-and-brimstone tests. One day when the Lorings' fifth child, Sarah, was two years old, she began to play hairdresser on one of the Newfoundlands with a pair of blunt cutout scissors. Mrs. Loring, who was in another room, heard the dog whimpering and when she investigated she found that Sarah had cut through the dog's hair and into his ear. The pup, in horrible pain, bleeding and crying, sat stoically; he refused to make a single move that might frighten the little girl.

The problem at first, the Lorings say, was to teach the younger children to show respect for the dogs, not the other way around. The Newfoundlands demonstrated their respect for the children in a constant diligence for their safety, especially around water. When the children used to go swimming last summer, Wendy, one of the Lorings' senior Newfoundlands, spent her day at the beach swimming a patrol back and forth in a stretch of water between the children's swimming area and the deep water. No Loring child had even an opportunity of swimming over his head with Wendy around. The only time she abandoned her self-appointed sentry duty was to take after two little boys, strangers to her, who had headed out from shore on a couple of inner tubes. Wendy kept a vigil over the boys until they paddled back to the beach, and then she resumed her normal patrol.

Occasionally Newfoundlands let their lifesaving instincts get just a little out cf hand — the way Trooper, a Newfoundland friend of the Lorings' dogs, once did. Trooper was strolling with his master along an ocean beach in Connecticut a couple of summers ago when he spotted a skin diver testing his equipment a few hundred feet off shore. Trooper, reacting as any normally heroic Newfoundland would, plunged into the water, made his way to the diver's side, and clamped his teeth into the diver's rubber suit just as he was about to launch a deep-sea plunge. The diver hadn't needed rescuing until Trooper appeared on the scene, but he was plainly terrified to find himself in the grip of a strange, hulking, black monster. Trooper's master, who realized that the dog was determined to save somebody that day, threw himself into the water and improvised a fake distress scene. Trooper abandoned the shaken diver and was delighted to perform a nick-of-time lifesaving job on his master. But back on the beach after all the heroics were finally over, the master wasn't all that pleased when he had to ante up the price of one punctured rubber diving suit.

In return for their Newfoundlands' concern and affection, the Lorings treat the dogs almost as members of the family. When young Joshua was hardly more than a baby, he was under the impression that Christopher, the first Loring Newfoundland, was a member of the family: the night Christopher died. Joshua asked his mother, in small-boy despair, "Who's going to look after me now?" (There was a new Newfoundland at the Loring house within forty-eight hours.)

The Lorings display their warm pride in the dogs, informally, to visitors at their home and, formally, at dog shows and competitions. Their Newfoundlands are frequent prize winners and one dog, Newkie, is only a point away from a Canadian championship. But the Lorings are careful to limit their enthusiasm for prizes so that the shows and training remain fun for the dogs: as they say, they want "happy-go-lucky dogs, not automatons." Which is the way it should be with members of the family.

The story of the world's centuries-old romance with the Newfoundland — the Lorings' relationship with their dogs has thousands of precedents — has been recorded in at least one "official" history and a couple of dozen unofficial chronicles. Newfoundlands, it turns out. have been the favorite pets of hundreds of famous people, from Richard Wagner (who coined the description of Newfoundlands as "nature’s gentlemen") to Franklin D. Roosevelt (whose dog was bred at Bing Crosby’s Newfoundland kennels). Newfoundlands have been acclaimed in poetry and paintings. They've been the beloved heroes of hundreds of shipwrecks and rescue missions at sea. And they have been deluged in oceans of blubbering owners' emotion.

Newfoundlands seem to decorate the foreground of more famous paintings than almost all other breeds of dog taken together. Artists from Velasquez to Currier and Ives have found special artistic merit in them. One of Renoir's loveliest paintings, Madame Charpentier and Children, includes, besides the mother and kids, a handsome, resplendent, black-and-white Landseer Newfoundland (named after famed artist Sir Edwin Landseer, who portrayed the breed in some of his paintings), and the dog has also been painted by Rubens, Reinagle and Krieghoff. It was this impressive array of names that inspired the famous critical point scored by an anonymous dog fancier: "I don't know much about art, but I know I like Newfoundlands."

Literature, as Newfoundland owners don't mind pointing out, isn't far behind painting in appreciating the dog's virtues. Sir Walter Scott and Charles Dickens were devoted Newfoundland admirers and the dogs often turn up in courageous roles in iheir novels. The dog in Dostoievski's The Idiot was a Newfoundland, and so was Nana, the nursemaid, in Peter Pan. Poets have frequently recorded their love for Newfoundlands in verse, but their Newfoundland poetry, alas, belongs more to the world of animal-loving than to the world of art. Some of the most extravagant but least memorable of the works of Lord Byron and Bobbie Burns, for instance, were inspired by Newfoundlands they knew. At one point in his career, Byron stipulated that he should be buried, under a monument, with his faithful Newfoundland pet at his side. He wasn't, but there's a wax Newfoundland sitting at the feet of a wax Lord Byron in Madame Tussaud's.

E. J. Pratt, the late dean of Canadian poets, chronicled his reverence for Newfoundlands in an epic verse about a life-saving dog named Carlo. Pratt thought enough of the poem to include it in his Collected Works, but his reputation is in jeopardy if it depends on brave Carlo:

I’ll not believe it Carlo; I

Will fetch you with me when I die,

And stand up at Peter’s wicket.

Will urge sound reasons for your ticket;

I'll show him your life-saving label

And tell him all about that cable,

The storm along the shore, the wreck,

The ninety souls upon the deck . . .

The Subject of all this adulation, as you might have deduced, was originally and exclusively a native of Canada’s tenth province. He evolved by natural selection, without any conscious attempt at breeding, from the hundreds of strains of ships' dogs dropped off in Newfoundland by the adventurers and fishermen who visited the island, beginning with John Cabot. (There's obviously a healthy dash of Eskimo Husky thrown in, too.) Gradually, the Newfoundland took on his distinctive shape and characteristics, including feet as webbed as a duck's, and in 1775 he was christened by one George Cartwright after his home island. About this time the dogs began to he exported to Europe where they were popular pets around the great eighteenthand nineteenth-century mansions and started turning up regularly in all those paintings and poems.

But back home the dogs weren't prospering in those years. In the late eighteenth century, a villainous governor named Edwards decided that Newfoundland should go into the sheep-raising business and, dogs being inimical to sheep, he issued a proclamation forbidding families on the island to own more than one dog each. Newfoundlands were slaughtered out of hand and their population and quality deteriorated rapidly. Despite the eventual repeal of the proclamation, the sad state of affairs continued until an incident in 1901 finally aroused one Newfoundlander to take steps to save the island’s most distinctive resident. That was the year that the Duke and Duchess of York, the future King George V and Queen Mary, visited Newfoundland and, obviously unaware that the breed had become almost extinct on the island, let it be known that they'd like a Newfoundland dog for the royal children. Local officials were frantic and it took a wild scrambling search to turn up, in a fishing village called Quidi Vidi, a suitable young dog.

The episode inspired one island official, Harold Macpherson, to undertake a program designed to restore the breed to its former glory. He was spectacularly successful. By the time Macpherson died in 1963, he had rescued the Newfoundland from the edge of extinction, bred it up to the highest standards, returned it to popularity in North America, and placed it on a Newfoundland stamp alongside George VI.

Today there are more than twenty-five hundred pedigreed Newfoundlands in Canada and the United States and the best Newfoundlands regularly triumph in show and obedience tests in dog competitions all over the continent. They're so prized that a good adult dog of championship stock would cost about five hundred dollars in 1965 — and the prices and population are still soaring. The Lorings breed a couple of litters of Newfoundlands each year — a normal Newfoundland litter runs to four or five dogs, but for a reason the Lorings can't explain, their bitches have produced litters of twelve, thirteen and fourteen pups — and they have no problem selling them. All a prospective purchaser has to do is spend an hour watching the fun the Loring kids get out of their four Newfoundlands — and he’s hooked.