[ Chatterbox ]

Chatterbox was a British weekly for children, which also published an annual edition in both the UK and the US. Begun in 1866, it published until 1955.

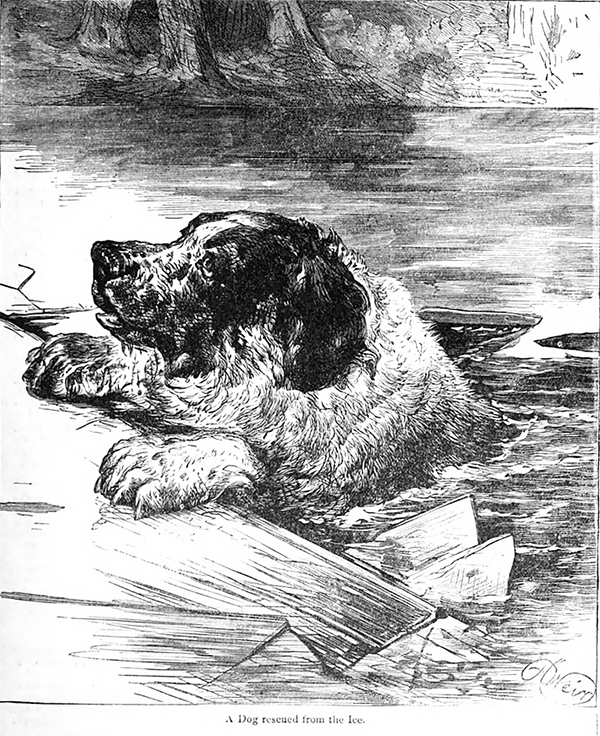

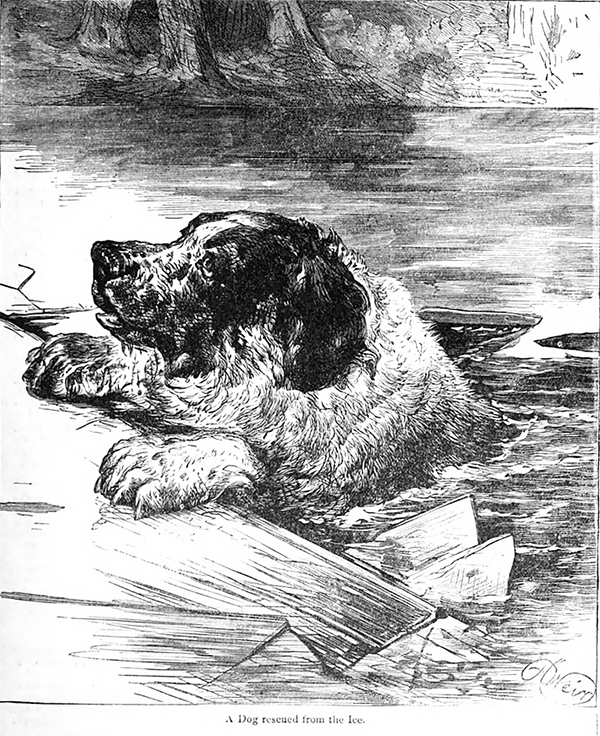

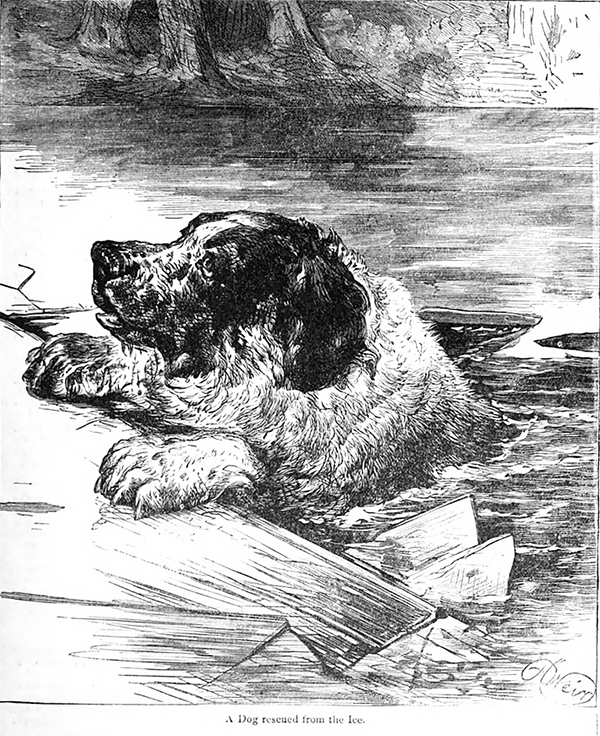

The 1882 annual carried several items featuring a Newfoundland, the first being "A Dog Rescued from the Ice," with an illustration by Harrison Weir, the noted English animal illustrator who, according to his Wiki entry, is also known as "the Father of the Cat Fancy" for organizing the very first cat show in England in 1871.

I went for a walk this afternoon into the country, and came on a piteous scene at a little inland lake not far from the barracks. A large Newfoundland dog had ventured on to the ice after a stick, and when in the very middle had fallen into an ice-hole, from which he was unable to extricate himself. When we had arrived he had been there an hour and a half. Poor thing ! he looked a noble creature even when in distress, his head and shoulders reared up by his fore-paws on the ice, appealing for succour. The owner was calling to him in a feeble, helpless sort of way. I asked his master why he did not go in and bring his dog out, but that seemed too ridiculous an idea to be entertained. As he did not seem worthy to possess the noble creature, I asked if he would give him to me if I saved him. "Yes," he said. "Off coat, and in!" said I. The ice was nearly thick enough to bear, which made it the more difficult to get on. W— threw me a plank, and by its help I worked my way. I wish you could have seen How the dog looked as he saw me getting nearer, for I can't describe it. However, it was done at last, and the dog was saved. I was done for, however, and had to crawl to the barracks not exactly in good parade order. I am bad at writing still, for both hands are cut about so much by the ice. (18)

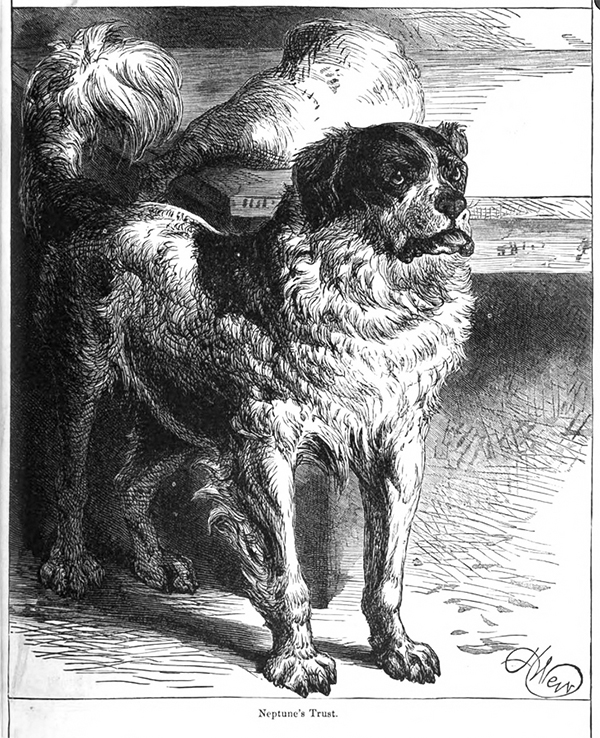

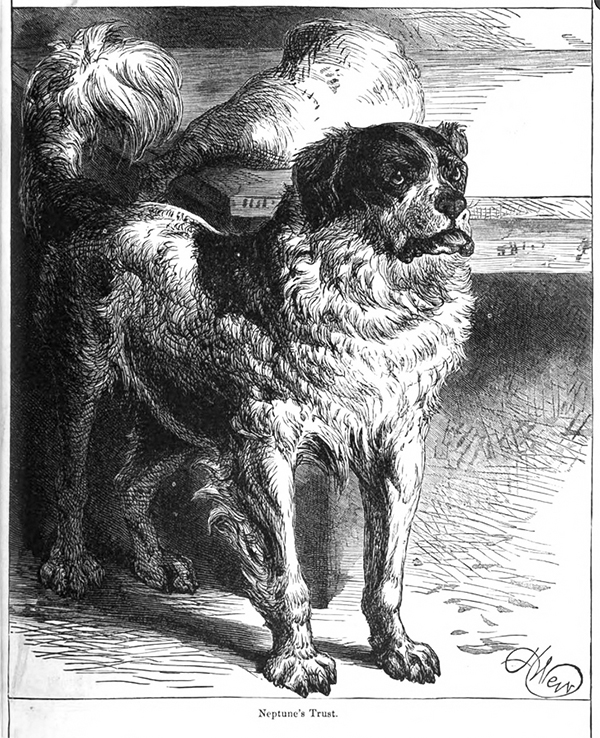

Next up is an anecdote entitled "Neptune's Trust":

A young farmer, whom we will call Mr. Smith, had a fine Newfoundland dog, of whose intelligence he often boasted. Some friends were staying with him; they had made arrangements for a day's fishing, and as the young men were going out, shortly after breakfast, they had to pass through the kitchen. Neptune was there, and seeing him at once set Mr. Smith off on his constant topic — the merits of his dog.

"He is as sensible a fellow as ever lived," he said, patting the great head which was thrust into his hand. "If I tell him to take care of a thing for me, he won't let anybody else touch it till I give him leave. I will prove this to you. There is a leg of mutton. Here, Neptune, mind this, and don't let any one touch it till I come back. Mind it, old fellow, and don't let anybody touch it till I come back."

Neptune stretched himself by the table, on which lay the joint for that day's dinner, wagging his tail at the same time, as if to say that he accepted the trust, and would hold himself responsible.

The young men left the kitchen; they had some preparations to make, which detained them for a few minutes, and then they set out on their excursion, forgetting all about Neptune and his charge.

The cook had been in the kitchen while the young men were there, and she went on with her work, without paying much attention to them; and now the potatoes were washed, and the turnips sliced, and it was time to put the leg of mutton down to boil. She went over to the table by which Neptune was lying, but as soon as she put out her hand to take the mutton he growled fiercely at her.

"What can be the matter with the dog?" she thought: "he isn't used to be so cross with me."

"Neptune! poor Neptune!" she said, coaxingly, patting the dog's head at the same time.

He received these caresses quietly, but as soon as she went near the joint of meat he showed her very plainly that she must not touch it.

"The mutton won't be boiled by dinner-time!" she exclaimed. "I'll go ask the mistress what I'm to do."

Mr. Smith's mother lived with him, and kept house for him; she was seated at work in her parlour, when the door opened and the cook came in, looking rather out of sorts.

"What am I to do, ma'am?" she said. "I think I heard the master telling Neptune, when he was going out, not to let any one touch the mutton till he came back; and now, when I wants to get it, to put it down to boil, he growls at me, and looks as if he was going to fly at me, and I'm afraid to take it from him."

"Nonsense, Betty!" said her mistress. "I didn't think you were so foolish as to be afraid of Neptune."

"Well, indeed, ma'am," said Betty, in rather an injured tone, "he'd bite me in a minute, and it would be no joke to have his big teeth stuck in one."

"But, you know, we must get it from him; it's all the meat we have in the house. I'll go down myself, and I'll soon set things to rights."

When Mrs. Smith went into the kitchen, the brave guardian of the mutton was still in the same spot beside the table.

"Poor Nep!" said his mistress, going up to him, and petting him in the most soothing manner. "Poor old Nep!"

Neptune took these caresses in very good part, but as soon as she attempted to touch the bone of contention he gave a fierce growl, that caused her to draw back just as quickly as Betty had done.

"Iíll tell you what you'll do, Betty," she said; "go into the dairy, and bring me a saucer of milk."

The milk was brought, and when it was placed near the dog he lapped it readily enough — still keeping an eye on the joint; but when it was moved over to the far end of the kitchen, nothing would tempt him to go to it. Bribes and caresses failed to move him, so Mrs. Smith resolved to try stronger measures, and she menaced Neptune with a stick; but although he had often submitted very meekly when she drove him out of the parlour, he seemed to consider himself in a post of honour now, and he showed very plainly that he would not permit any indignities. After nearly an hour spent in vain efforts to get possession of her dinner, Mrs. Smith left the kitchen, feeling a little irritated at her want of success, whilst Betty secretly chuckled at the way in which her mistress had "set things to rights."

Meanwhile the young men had a pleasant day at the river, although they could not boast of much success in fishing, and as time went on they began to feel tired and hungry. Most of the party had a few perch or pike to produce, but one of them complained that he had not even got a bite.

"Well," said Smith, "I believe the best way to secure that will be to go home to dinner. I know I am as hungry as a hunter."

"And so am I," said another. "I hope your mother has a good dinner for us: I intend to astonish her."

"I think I heard something about a boiled leg of mutton."

"Capital!" exclaimed another. "There's nothing I like so well as a boiled leg, with caper sauce and plenty of turnips round it."

When the party reached the farm, they went into the room where Mrs. Smith was sitting. "Mother," said Smith, "is dinner nearly ready? We're all starved, and we've been having visions of a boiled leg of mutton."

"It's all you're likely to have of it, then," said his mother. "It seems you told Neptune not to let anybody touch the mutton while you were away, and it would have been as much as one's life was worth to go near it ever since." And Mrs. Smith gave a full account of her adventure — or, rather, misadventure — with the dog.

The young men looked rather disappointed for a moment, and then the absurdity of the whole affair struck them, and there was a general laugh.

The party repaired to the kitchen, where they found the grim sentinel still at his post.

"And so you wouldn't let them touch the mutton, Nep!" said his master. "That's a good dog! a very good dog! and you may go now. There, Betty, take our leg."

"And what am I to do with it now, ma'am? it would be over two hours before it would be boiled."

"You must just cut it into slices, and broil it for us; if the gentlemen are as hungry as they say, they won't quarrel with it."

Dinner was soon ready, and by the time the young men had appeased their appetites with a few slices of the broiled mutton they were ready to declare that the whole thing was a capital joke, and that Neptune was the best dog in the world. But I think, ever afterwards, Mr. Smith was more careful what orders he gave his dumb servant, when he found they were so faithfully carried out. M. L'E. (50 - 51)

A Newfoundland is mentioned in one other story in this volume, a historical tale involving Scotland's early struggle for independence. A young girl accompanied in the fields by her Newfoundland encounters Sir William Wallace, one of the leaders of Scotland's early independence movement, and he asks her to bring him food, and to say nothing of their encounter. The Newf figures only incidentally, and of course is an egregious historical anachronism: Sir William Wallce — the subject of the 1995 Mel Gibson movie Braveheart — was executed (very gruesomely) in 1305, over 400 years before the first historical mention of Newfoundland dogs.

Perhaps fittingly, this final tale has an illustration but it does not include the Newfoundland.