[ Drury / British Dogs ]

The text here is that of the third edition of British Dogs: Their Points, Selection, and Show Preparation edited by Drury and published in London by L. Upcott Gill and in New York by Charles Scribner's Sons.

A number of individuals are credited as "collaborators" on many of the entries in this book, but no collaborator is listed for the Newfoundland entry. Which may be a bit dishonest, as at least several passages from the Newfoundland entry are copied almost word for word from Hugh Dalziel's 1879 British Dogs (also treated here at The Cultured Newf).

Newfoundlands are mentioned five or six times in this book as they related to other dog breeds (the Labrador Retriever, Spaniels, and the St. Bernard, specifically); Chapter VI (pp. 56 - 66) is devoted solely to discussion of the Newfoundland, including a nice treatment of the history of color patterns in Newfs -- which at one point in the early C19 were regarded by some as being primarily white. Much of the chapter deals with show standards. The photographs are placed at approximately those points where they occur in the printed volume.

AROUND the Newfoundland centres a halo of romance hardly less bright than that investing the St Bernard. Both are life-savers, and, strange to say, both are importations so far as this country is concerned; while they are two varieties of the Domestic dog that even the child is from very early times taught to venerate. As to whether Sebastian Cabot, when he discovered Newfoundland in 1497, found dogs of a remarkably large size and noble appearance, history is silent. No naturalist, sportsman, or other writer that treats of dogs before the end of last century says anything about the Newfoundlander, as he has sometimes been called.

The European settlers in Newfoundland were at one time principally Irish and natives of the Channel Islands. The question arises, Did these settlers, or others from England or France, take with them dogs of a large sort from Europe, which, being crossed with the native dogs, improved the latter, and gradually formed a new variety ? It is not necessary to suppose this to have occurred

in the earliest days of the settlement, for there has been a growing intercourse ever since, and the introduction of one or more of our large and superior races of dogs, from the beginning to the middle of the eighteenth century, would give ample time for the formation of a new breed of dog in Newfoundland, by commixture of their blood with that of the native race, before imported Newfoundland dogs became popular in this country.

Writers constantly speak of the pure breed of dog indigenous to Newfoundland, and lament that he is now only to be met with

mongrelised through crosses with inferior races. If the native inhabitants — the Mic Macs — possessed a dog of the high intellectual and moral character of the Newfoundland as now known, it would indeed be an astonishing fact. Such a supposition is highly improbable, the more probable theory being that Europeans made the breed now recognised as the Newfoundland. The breed seems to have become popular in England during the last half of the eighteenth century, Bewick and other contemporary writers referring to it as being then well known. Many interesting stories of the time are told of lives saved from sea and river by the intelligence and bravery of this noble dog.

The Newfoundland undoubtedly had its full share of public attention, and long before dog shows were in existence, or the finely

drawn distinctions respecting " points" were called into being, he reigned paramount in the affections of the British public as a

companion, an ornament, and a guard. But in those days every man had his own ideal standard of excellence, or borrowed a suitable one from a doggy friend, the suitability being insured by alteration sufficient to make it applicable to his own pet — a processnot yet entirely obsolete.

Many of these large, so-called Newfoundland dogs of forty-five to sixty years ago had been imported, or were the immediate

descendants of such; but they differed materially in colour, coat, and in other minor points, from each other, and still more from

what in this country is now held to be the Newfoundland proper. There was a decided difference between dogs imported from

Newfoundland into Liverpool some fifty years ago, though by their importers each believed to be the pure breed. The difference,

however, was more in the sort of coat and the colour than in the other marked characteristics of the breed, which they all had in

common with the recognised dog of the day.

The decided differences then existing in these dogs in this country was also common in those of the Island of Newfoundland,

and still continues; and this obscures the interesting question, What was the original breed of the Island really like ? and prepares us for the very wide difference and rather dogmatic expression of opinion on the subject by gentlemen who have had the advantage of a residence there, and who have afterwards joined in public discussion on the question.

Many years ago the late Mr. William Lort (who spent some portion of his early life in Newfoundland), in giving some reminiscences to a few friends, referred to the dogs. He said that, although a variety of big mongrels were kept and used there, those that the natives of the Island looked on as the true breed were the black or rusty black, with thick and shaggy coats, and corresponding in all other points — although, from want of proper culture, inferior — to our best specimens of the day.

Against this testimony may be quoted the opinion of "Index," who in the Field, nearly a quarter of a century ago, wrote on this subject with great pertinence, and, evidently from personal observation, declared the true breed to be of "an intense black colour," and "with a small streak of white, which is upon the breasts of ninety-nine out of every hundred genuine dogs."

Per contra, "Otterstone," in the Country, January 6th, 1876, says: "The predominant colour of the 'Newfoundland proper' is white. His marks are nearly invariable, namely, a black head or face mark, a black saddle mark, and the tip of the stern also black." "Otterstone" also wrote from personal observation of the dogs accepted as pure Newfoundlands in Canada.

Others wrote not only about colour, but also about texture of coat, some holding that it should be curly, others wavy, others shaggy; while as to the height of the original, this is variously stated as 24in. to 26in., up to 30in. and 32in.

In the "Sportsman's Cabinet," published in 1802, is an engraving of the Newfoundland from a drawing by Reinagle. The dog represented is like our modern one in most points, but not so big and square in head, altogether lighter in build, and almost entirely white. No specific description follows, the author evidently considering that the artist so well conveys the impression as to the general appearance as to render such unnecessary.

Whether there was a dog of marked characteristics from other recognised breeds found indigenous to the Island on its discovery or not, we may accept the case as proved that they are now, from various causes, a mixed lot, greatly inferior to our English Newfoundlands. At one time the lesser Newfoundland was recognised; but whatever claims to recognition such a dog may have had in the past, it is certain that none exist in the present, except such as may be found in the Wavy-coated Retriever, which variety was evolved from the smaller Newfoundlands.

The contention of those who say the original breed — using the expression to mean the breed as it was when we began to import these dogs — did not stand more than about 25in. at the shoulder is greatly discounted by references to the size and dignified appearance of the dog by older writers; and although climate and good care do much, their effects would hardly be so immediate and so great as to make a 30in. dog out of a pup which, left at home, would only have grown to 25in., or that that result would follow except after a considerable number of years of careful breeding; but in the "Sportsman's Cabinet," nearly seventy years before "Index" wrote in the Field, and his dictum as to height was accepted by "Stonehenge," the dog was stated to be valued for his great size. Nor is size any less highly esteemed at the present day, so long as it is not obtained at the expense of character.

By many the Newfoundland is given an unjust character as regards temperament. Taken as a breed, the dogs are good-tempered and generally to be moulded into the best of companions if their education be but taken in hand sufficiently early. That there are bad-tempered Newfoundlands cannot be denied; but such a fault is individual, and not that of the breed as a whole.

[ This is the first of two Newfoundland images illustrating this chapter of Drury's book.

The caption reads "Fig. 27 - White and Black Newfoundland 'His Nibs'"

("his nibs" is an archaic term referring to someone with a great deal of self-importance). ]

There is certainly a dignity of demeanour, a noble bearing, and a sense of strength and power, though softened by the serenity of his countenance and deeply sagacious look, which cannot be dissociated from great size, and these were among the good qualities which commended this dog to public favour. The Newfoundland's good qualities, however, do not rest here; he is of a strongly emulative disposition, extremely sensitive to either praise or censure, and should therefore, especially when young, be managed with great care. He is never so well satisfied as when employed for either the pleasure or the advantage of his master, and his strong propensity to fetch and carry develops itself naturally at an early age.

As a water dog the Newfoundland has no equal — he delights in it, will almost live in it — and his high courage and great swimming powers might with benefit to mankind be oftener turned to account.

If we continuously breed from prize winners, however grand in appearance, which are uneducated, and have their natural powers undeveloped—indeed, checked—we shall soon have lost sterling qualities, and get in return mere good looks. But the two things — fine physical development, with high cultivation of those instincts and natural powers — are not incompatible, and should be simultaneously encouraged by dog-show promoters, just as the Kennel Club does for Pointers and Setters by their field trials.

Water trials of Newfoundlands were held at Maidstone Show and at Portsmouth some twenty-five years since; but neither could be pronounced a brilliant success. They were each of them in many respects interesting, and proved that, with more experience, and if well carried out, such competitive trials might become more than interesting — highly useful.

Later the British Kennel Association had a dog show at Aston, near Birmingham, and had water trials in connection with it. Many of the competing dogs exhibited intelligent capacity, but the place was unsuitable and the arrangements were very defective.

Competitive trials will one day perhaps be established as a means of proving to the public, in an interesting way, how best to use the valuable services of the Newfoundland dog in the saving of human life. If so, the following excellent rules, drafted for the conduct of public water trials of dogs at Maidstone, may be of service: —

TESTS FOR WATER DOGS

1st. Courage displayed in jumping into the water from a height to recover an object. The effigy of a man is the most suitable thing.

2nd. The quickness displayed in bringing the object ashore.

3rd. Intelligence and speed in bringing a boat to shore— the boat must, of course, be adrift, and the painter have a piece of white wood attached to keep it afloat, mark its position, and facilitate the dog's work.

4th. To carry a rope from shore to a boat with a stranger, not the master, in it.

5th. Swimming races, to show speed and power against stream or tide.

6th. Diving. A common flag-basket, with a stone in the bottom of it, to sink it, answers well, as it is white enough to be seen, and soft enough to the dog's mouth.

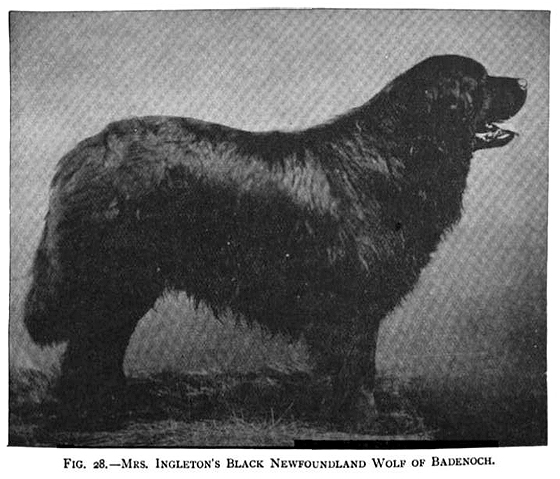

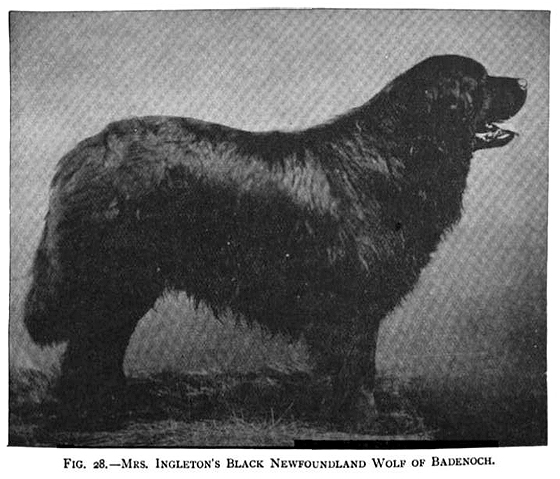

In the early days of the Newfoundland the dog was met with in colours other than black and white-and-black, and not only that, but prizes were awarded to livers and bronzes. To-day the two varieties most sought are the Black and the White-and-black (Figs. 27 and 28). The latter has been immortalised by Landseer in his world-famous picture of "A Distinguished Member of the Humane Society," though it must be confessed that the dog taken as a model would certainly not pass muster in the present day, the coat, to go no further, being of the curly order, instead of flat, as the Club's description requires. The White-and-black has not progressed so rapidly as the Black, except perhaps in the south, where it has made great strides, though neither may be said to be popular in the strictest sense of that term. This, however, is due rather to Fashion's vagaries than to any shortcomings on the part of the variety. The first year of the twentieth century certainly shows an improvement as compared with the declining years of the nineteenth.

Coats generally are alike better as to texture and arrangement, and what in the case of the show dog of old had largely to be done by resorting to little tricks has been remedied to a very great extent by the breeder. Eyes, again, are darker in colour, much better placed, and smaller in size than once they were, and as it is the eyes that are largely responsible for the expression so noticeable in the Newfoundland, the improvement in the directions stated are not without their value upon the breed.

Allusion has already been made to size, and the value set upon it so long as it is obtained without the loss of quality. And here, also, the present-day dog scores over those of a decade ago. The improvement shown in the White-and-black dogs continues, as breeders have recognised that if these are to equal in type the best of the Blacks, the finest specimens of both will have to be "worked." The old-time breeder, in his anxiety to obtain a big dog, often only succeeded in producing a long-legged, weak-faced, slab-sided, straight-behind monstrosity, and not a typical Newfoundland. The defects just mentioned must be carefully guarded against when breeding, as also must light eyes and badly carried and twisted tails. Faults of any kind are always easier of perpetuation than they are of eradication.

No really practical purpose is to be served by enumerating the many good dogs that have been produced since the publication of pedigrees. These may be learned by a careful study of the Kennel Club Stud Book. It may, however, be remarked that of the older dogs some of the more renowned, and that have become pillars of the Stud Book, are: Nelson I., Courtier, Thora L and Thora II., Mrs. Cunlifle Lee's Nep, Leo, Lion, Lady Mayoress, Lord Nelson, Lady-in-Waiting, Merry Maiden, Triumph, Hanlon, etc. And for a strain of Blacks those associated with either Courtier or Nelson would be difficult to beat. Of the White-and-black, or Landseer variety, as Dr. Gordon Stables named it, Dick, Prince Charlie, Bonnie Swell, Bonnie Maid, Rosebud, His Nibs (Fig. 27), Kettering.

[ This is the second of two Newfoundland images illustrating this chapter of Drury's book.

"The Wolf of Badenoch" was a nickname given to the Scottish nobleman Alexander Stewart (1343 - 1394/1406?),

known for his pillaging, looting, raping, and other nefarious activities.

As an illegitimate son of the King, Stewart's penchant for violent amusement was repeatedly overlooked.

Not much of a role model, but ya gotta admit – "Wolf of Badenoch" sounds pretty cool. ]

Wonder, are but a few that occur. As an excellent example of the Courtier type of dog Wolf of Badenoch (Fig. 28) may be cited.

The Newfoundland does not call for any special treatment by way of show preparation, except perhaps in the grooming. Novices sometimes err in respect of this latter by parting the hair. This should never take place: the dog should be brushed and combed from head to tail. Though, as stated by Mr. Lort, it is not uncommon to find a sort of rustiness of hue in many Black Newfoundlands, and these too of the best, yet this must not be confused with the all-brown specimens sometimes occurring in litters. The Newfoundland, like all the giants of the canine race, takes some two years and more to build up its massive frame, and this must be duly borne in mind. Meat should oftener enter into the dietary than is the case with the smaller varieties, though when using this for young puppies, it should be of such a kind that it is readily assimilated. For that reason such meat as well-cooked tripe or paunch will be found the best for the puppies until such times as the permanent teeth commence to be erupted. Exercise for heavy breeds should be of the walking kind, and as soon as the feet are hard enough upon the roads. No puppy should be chained to a kennel. If this takes place while the bones are at all soft, the heavy frame tugging at a chain will soon pull out of shape the most promising of puppies. In selecting a young puppy — say one at six months old, a most useful age to commence with — the head properties should be the chief criterion. If there is not abundant promise of a massive head at the age named, it may be taken for granted that such a puppy is not likely to finish well. A Newfoundland should also show early in life promise of plenty of bone; dark eyes, straight forelegs, and a dense flat coat must also be found on a puppy of promise. Tail-carriage in any puppy must not be too seriously regarded until after the period of dentition is complete. Many puppies carry both tails and ears irregularly while teething.

The Newfoundland Club has been established many years and has worked well in the interest of the breed. It has drawn up a description of the breed on the lines given below: —

Symmetry and General Appearance. – The dog should impress the eye with strength and great activity. He should move freely on his legs, with the body swung loosely between them, so that a slight roll in gait should not be objectionable; but at the same time a weak or hollow back, slackness of the loins, or cowhocks should be a decided fault.

Head, – Should be broad and massive, flat on the skull, the occipital bone well developed ; there should be no decided stop, and the muzzle should be short, clean cut, rather square in shape, and covered with short fine hair.

Coat. — Should be flat and dense, of a coarsish texture and oily nature, and capable of resisting the water. If brushed the wrong way, it should fall back into its place naturally.

Body. — Should be well ribbed up, with a broad back. A neck strong, well set on to the shoulders and back, and strong muscular loins.

Fore Legs. — Should be perfectly straight, well covered with muscle, elbows in but well let down, and feathered all down.

Hindquarters and Legs. — Should be very strong; the legs should have great freedom of action, and a little feather. Slackness of loins and cowhock are a great defect; dew-claws are objectionable, and should be removed.

Chest. — Should be deep and fairly broad and well covered with hair, but not to such an extent as to form a frill.

Bone. - Massive throughout, but not to give a heavy, inactive appearance.

Tail. — Should be of moderate length, reaching down a little below the hocks; it should be of fair thickness and well covered with long hair, but not to form a flag. When the dog is standing still and not excited, it should hang downwards, with a slight curve at the end ; but when the dog is in motion, it should be carried a trifle up, and when he is excited, straight out, with a slight curve at the end. Tails with a kink in them, or curled over the back, are very objectionable.

Feet. — Should be large and well shaped. Splayed or turned-out feet are objectionable.

Ears. — Should be small, set well back, square with the skull, lie close to the head, and covered with short hair, and no fringe.

Eyes. — Should be small, of a dark brown colour, rather deeply set, but not showing any haw, and they should be rather widely apart.

Colour. — Jet black. A slight tinge of bronze, or a splash of white on chest and toes is not objectionable.

Height and Weight. — Size and weight are very desirable so long as symmetry is maintained. A fair average height at the shoulders is 27in. for a dog and 25in. for a bitch, and a fair average weight is respectively: dogs, 140lb. to 150lb.; bitches, 110lb. to 120lb.

Other than Black. — Should in all respects follow the black except in colour, which may be almost any, so long as it disqualifies for the Black class, but the colours most to be encouraged are black-and-white and bronze. Beauty in

markings to be taken greatly into consideration.

Dogs that have been entered in Black classes at shows held under Kennel Club Rules, where classes are provided for dogs Other than Black, shall not be qualified to compete in Other than Black classes in future.

Black dogs that have only white toes and white breasts and white tip to tail are to be exhibited in the classes provided for Black.

SCALE OF POINTS

Head.......................................................................... 34

Shape of Skull........................................ 8

Ears....................................................... 10

Eyes...................................................... 8

Muzzle.................................................... 8

Body ........................................................................ 66

Neck...................................................... 4

Chest...................................................... 6

Shoulders............................................... 4

Loin and Back...................................... 12

Hindquarters and Tail........................... 10

Legs and Feet........................................ 10

Coat...................................................... 12

Size, Height, and General Appearance... 8

____

Total points in all............................... 100

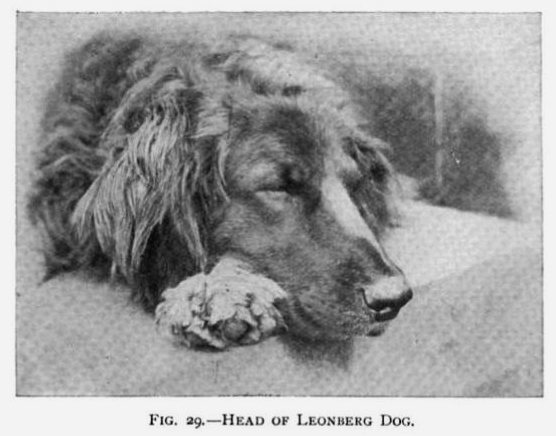

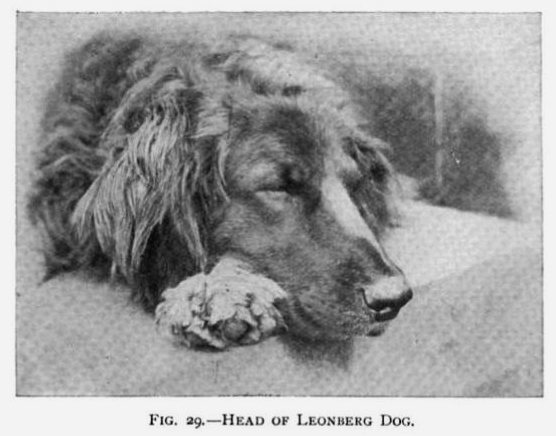

We may very well mention here a variety of dog that is occasionally met with at shows in this country and that is undoubtedly a combination of the Newfoundland and some other breed, probably the Great Dane. The dog referred to is the Leonberg. Though not very highly thought of in England, yet upon the Continent there is at least one club that fosters the breed. In colour it is reddish, and the head is well shown in the illustration (Fig. 29), prepared from a photograph kindly placed at our disposal by Mr. W. H. Fawkes, of the Vicarage, Harrogate. The head has the occipital bone well developed, the eyes are of medium size, brown, expressive, and intelligent-looking. The ears are set on high and carried slightly forward. White patches on the body are not admissible; but a little white upon the breast and feet (as seen in some Newfoundlands) is tolerated by those that regard the dog as a distinct variety breeding true to type. Anything, however, suggestive of a St. Bernard cross is not tolerated.