[ Hawker / Instructions to Young Sportsmen ]

Lt. Col. Peter Hawker (1786-1853) was an English military officer and writer on military and sporting subjects.

The full title of this book is Instructions to Young Sportsmen, with Directions for the Choice, Care, and Management of Guns; Hints for the Preservation of Game; and Instructions for Shooting Wildfowl. To which is added, a concise abridgment of the principal game laws. It was first published in 1814, with a second edition in 1816, a third in 1824, and more editions well into the middle of the 19th Century, with some of those later editions being edited by Hawker's son, Major P. W. L. Hawker. Clearly a popular work... The text below is taken from the third edition (London: Longman, Hurst Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green).

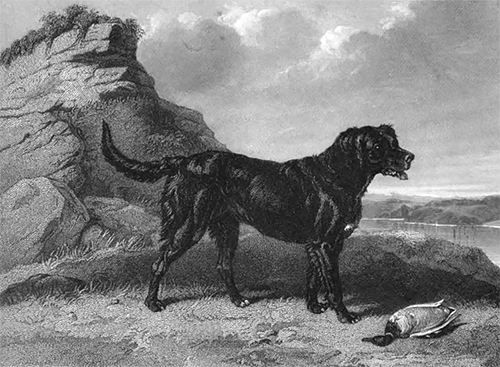

The only illustration in this work which depicts a dog is reproduced below; most of the 10 plates are of hunting equipment or dog-training collars. The dog pictured below does not really seem to be a Newf as we know the breed now. As you can see below, Hawker seems most interested in what he terms "St. John's breed of these animals," which seems to refer to what we now know as Labrador retrievers. (For Hawker, "Labrador" Newfoundlands are the larger and more substantial of the two "Newfoundland" types, and seems to refer to what we now call the Newfoundland.)

There is a good deal of training advice in this book, particularly in training gun dogs; the author is very much a product of his time and, as in the section on Newfoundlands below, is a strong believer in whipping and beating dogs as part of their routine training.

The first mention of Newfoundlands occurs during a discussion of pheasant shooting:

For one alone to get shots in a thick underwood, a brace or two of very well broke spaniels would, of course, be the best. But, were I obliged to stake a considerable bet (taking one beat with another, where game was plentiful), I should back, against the sportsman using them, one who took out a very high couraged old pointer, that would keep near him, and would, on being told, break his point to dash in, and put the pheasants to flight before they could run out of shot. This office may be also performed by a Newfoundland dog; but, as first getting a point would direct the shooter where to place himself for a fair shot, the Newfoundland dog would always do best kept close to his heels, and only make use of to assist in this ; and particularly for bringing the game; as we rarely see a pointer, however expert in fetching his birds, that can follow and find the wounded ones half so well as the real St. John's Newfoundland dog. (152)

The next mention occurs in a section on deer hunting:

If he [the buck] is pretty wild, and sees the man behind him, he will come bounding with such rapidity, that the most expert rifleman may miss him. In this case, a pretty stout gun, loaded with a mixture of mould and A or B shot, would be your best chance. If with this, however, you even mortally wound him, the chances are twenty to one, that he continues his course with unabated speed ; so that, instead of beginning to despair, you must follow him up as fast as possible, by doing which, you will most likely find him dying in some hedgerow, a few fields distant. For this purpose a Newfoundland dog is very useful, as the moment the dog has run up to him in the covert he will begin bellowing so loud as to be easily discovered. (195)

In a discussion of duck hunting and retrieving dead birds:

I must, therefore, to be on the safer side, recommend my young pupils to use either a Newfoundland dog, a mute water spaniel, or an old pointer that will keep close, and fetch dead birds.

The above recommendation is referenced, mostly verbatim, in a brief note on "Wild Duck Shooting" which appeared in New Sporting Magazine of October, 1835, p. 405.

Keep in mind that much of what Hawker writes, in the following section, deals with dogs we now know as the Labrador Retriever.

NEWFOUNDLAND DOGS

Here we are a little in the dark. Every canine brute, that is nearly as big as a jackass, and as hairy as a bear, is denominated a fine Newfoundland dog. Very different, however, is both the proper Labrador and St. John's breed of these animals; at least, many characteristic points are required, in order to distinguish them.

The one is very large; strong in the limbs; rough haired; small in the head; and carries his tail very high. He is kept in that country for drawing sledges full of wood, from inland to the sea shore, where he is also very useful, by his immense strength and sagacity, among wrecks, and other disasters in boisterous weather.

The other, by far the best for every kind of shooting, is oftener black than of another colour, and scarcely bigger than a pointer. He is made rather long in the head and nose; pretty deep in the chest; very fine in the legs; has short or smooth hair; does not carry his tail so much curled as the other; and is extremely quick and active in running, swimming, or fighting.

Newfoundland dogs are so expert and savage, when fighting, that they generally contrive to seize some vital part, and often do a serious injury to their antagonist. I should, therefore, mention, that the only way to get them immediately off is to put a rope, or handkerchief, round their necks, and keep tightening it, by which means their breath will be gone, and they will be instantly choked from their hold.

The St. John's breed of these dogs is chiefly used on their native coast by fishermen. Their sense of smelling is scarcely to be credited. Their discrimination of scent, in following a wounded pheasant through a whole covert full of game, or a pinioned wild fowl through a furze brake, or warren of rabbits, appears almost impossible. (It may, perhaps, be unnecessary to observe, that rabbits are generally very plentiful, and thrive exceedingly, near the sea shore. It, therefore, often happens, that wigeon, as they fly, and are shot, by night, fall among furzebrakes, which are full of rabbits.)

The real Newfoundland dog may be broken in to any kind of shooting; and, without additional instruction, is generally under such command, that he may be safely kept in, if required to be taken out with pointers. For finding wounded game, of every description, there is not his equal in the canine race; and he is a sine quâ non in the general pursuit of wildfowl.

Pool was, till of late years, the best place to buy Newfoundland dogs; either just imported, or broken in : but now they are become much more scarce, owing (the sailors observe) to the strictness of "those ——— the tax gatherers." I should always recommend buying these dogs ready broken; as, by the cruel process of half starving them, the fowlers teach them almost every thing; and, by the time they are well trained, the chances are, that they have got over the distemper, with which this species, in particular, is sometimes carried beyond recovery. If you want to make a Newfoundland dog do what you wish, you must encourage him, and use gentle means, or he will turn sulky; but to deter him from any fault, you may rate or beat him.

I have tried poodles, but always found them inferior in strength, scent, and courage. They are also very apt to be sea-sick. The Portland dogs are superior to them. A water dog should not be allowed to jump out of a boat, unless ordered so to do, as it is not always required; and, therefore, needless that he should wet himself, and every thing about him, without necessity.

For a punt, or canoe, always make choice of the smallest Newfoundland dog that you can procure; as the smaller he is, the less water he brings into your boat after being sent out; the less cumbersome he is when afloat; and the quicker he can pursue crippled birds upon the mud. A bitch is always to be preferred to a dog in frosty weather, from being, by nature, less obstructed in landing on the ice.

If, on the other hand, you want a Newfoundland dog only as a retriever for covert shooting; then the case becomes different; as here you require a strong animal, that will easily trot through the young wood and high grass with a large hare or pheasant in his mouth. (256 - 260)

And finally this advice for shooting from a canoe:

We know that Hawker practiced what he preached by owning a Newfoundland (of the "St. John's" variety) himself; an article on "Wild Fowl Shooting in November" in the November, 1861, issue of Sporting Magazine makes reference to shooting near the English town of Lymington, where "the late Lieutenant-Colonel Peter Hawker" lived with "his much-fondled Newfoundland" during the shooting season. (368)

That same magazine also mentions the good Colonel's fondness for Newfoundlands — that is, "St. John's Newfoundlands," which we now know as Labrador retrievers — in an article, published in the January, 1861, issue celebrating the achievements of a retriever named "Tar": "Colonel Hawker, who answers for Tar's excellence on the bitch's side, had himself a great fancy for the Newfoundland dog; “not every brute as big as a jackass, and as hairy as a bear,” but the proper Labrador and St. John's breed. . . ." (68)

The following engraving of "Tar" accompanied that article, and showed the style of dog the Colonel preferred. The remark in the quote just above, that the Colonel "answers for Tar's excellence on the bitch's side" refers to the fact that Tar was out of a bitch owned by Col. Hawker.