[ Hutchinson / Dog Breaking ]

Full title: Dog breaking: the most expeditious, certain and easy method: whether great excellence or only mediocrity be required: with odds and ends for those who love the dog and gun. First published in 1848 (London: John Murray), with multiple later editions and revisions into the 1890s.

W(illiam). N(elson). Hutchinson (1803-1895) was an English military officer and writer on sporting topics.

The text below is from the 7th edition (1882, published in London by John Murray).

As this is a book devoted largely to training sporting dogs, Newfoundlands are first mentioned in terms of being crossed with setters or retrievers in order to get stronger sporting dogs:

. . . the best land retrievers are bred from a cross between the setter and the Newfoundland, or the strong spaniel and the Newfoundland. I do not mean the heavy Labrador, whose weight and bult is valued because it adds to his power of draught, nor the Newfoundland, increased in size at Halifax and St. John's to suit the taste of the English purchaser; — but the far slighter dog reared by the settlers on the coast, a dog that is quite as fond of water as of land, and which in almost the severest part of a North American winter will remain on the edge of a rock for hours together, watching intently for anything the passing waves may carry near him.

Probably a cross from the heavy, large-headed setter, who, though so wanting in pace, has an exquisite nose, and the true Newfoundland, makes the best retriever.(73)

Yet Hutchinson's primary interest in sporting dogs doesn't prevent him from recounting several anecdotes about Newfoundlands. The first comes in the book's chapter on teaching tricks to dogs as a way of beginning their training:

A cousin of one of my brother officers, Colonel A——n, was talking a walk in the year '49, at Tunbridge Wells, when a strange Newfoundland made a snatch at the parasol she held loosely in her hand, and quietly carried it off. His jaunty air and wagging tail plainly told, as he marched along, that he was much pleased at his feat. The lady civilly requested him to restore it. This he declined, but in so gracious a manner that she essayed, though ineffectually, to drag it from him. She therefore laughingly, albeit unwillingly, was constrained to follow her property rather than abandon it altogether. The dog kept ahead, constantly looking round to see if she followed, and was evidently greatly pleased at perceiving that she continued to favour him with her company. At length he stepped into a confectioner's, where the lady renewed her attempts to obtain possession of her property; but as the Newfoundland would not resign it, she applied to the shopman for assistance, who said that it was an old trick of the dog's to get a bun; that if she would give him one he would immediately return the stolen goods. She cheerfully did so, and the dog as willingly made the exchange.

I'll be bound the intelligent animal was no mean observer of countenances, and that he had satisfied himself, by a previous scrutiny, as to the probability of his delinquencies being forgiven. (92)

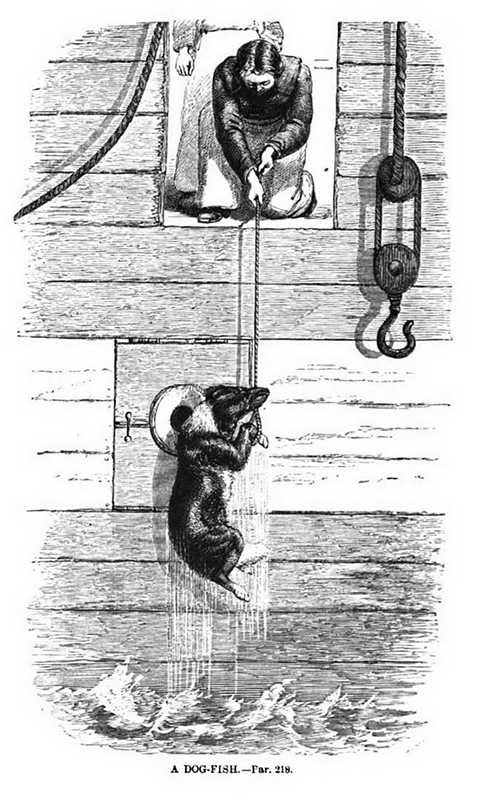

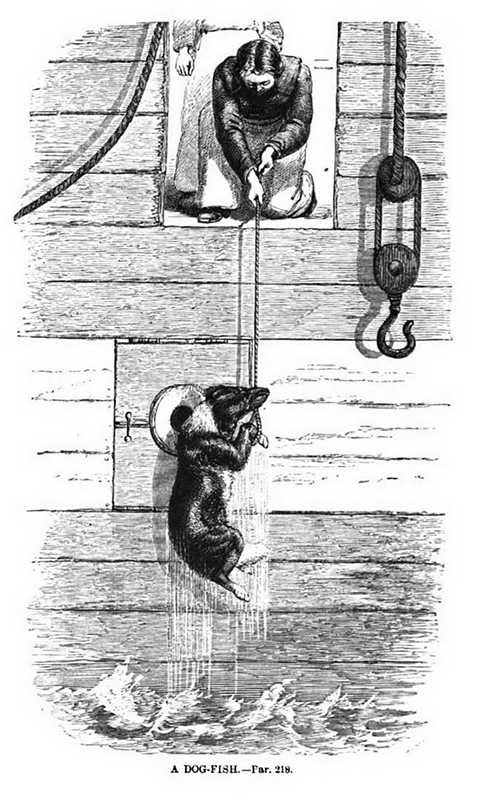

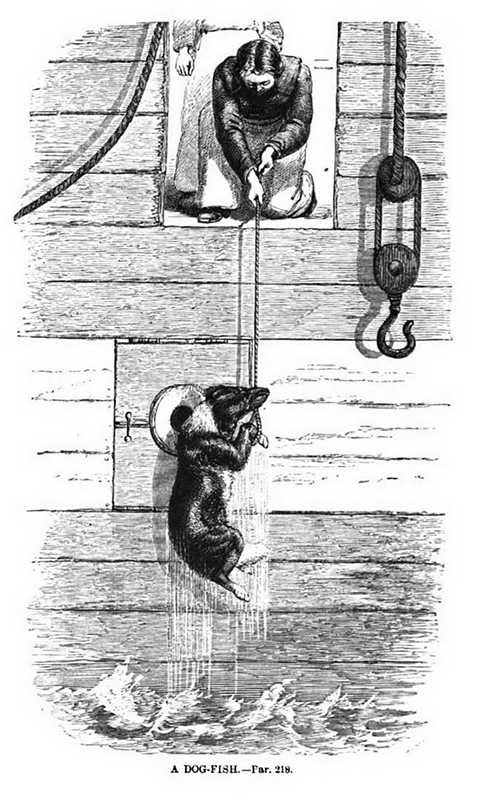

In Chapter 7, which treats of "Nature's Mysterious Influences," Hutchinson has two stories to tell of uncanny nautical Newfoundlands. The first anecdote is illustrated with the following image:

Captain G——g, R. N., mentioned to me that a ship in which he had served many years ago in the Mediterranean seldom entered a port that the large Newfoundland belonging to her did not jump overboard the instant the anchor was dropped, swim ashore, and return, after an hour or two's lark, direct to his own ship, though she might be riding in a crowd of vessels. He would then bark, anxiously, until the bight of a rope was hove to him. Into this he would contrive to get his fore-legs, and, on his seizing it firmly with his teetch, the sailors, who were much attached to him, would hoist him on board.

Mr. W——b, of S—a, had a young Newfoundland that from very puppyhood took fearlessly to water, but acquired as he grew up such wandering propensities on land that his master determined to part with him, and accordingly made him a present to his friend Lieut. P——d, R. N., then in command of H. M. Cutter "Cameleon." "Triton," however, was so attached to his old roving habits that whenever the cutter went into port he would invariably swim ashore of his own accord, and remain away for several days, always managing, however, to return on board before the anchor was weighed. Such, too, was his intelligence that he never seemed puzzled how to pick out his own vessel from amidst forty or fifty others. Indeed, Lieut. P——d (he lately commanded the "Vulcan"), to whom the question, at my request, was expressly put, believes (and he has courteously permitted me to quote his name and words) that, on one occasion, "Triton" contrived to find his own vessel from among nearly a hundred that were riding at anchor in Poole harbour. The dog's being ever so well acquainted with the interior of the craft does not explain why he should be familiar with her external appearance. Did he judge most by the hull or the rigging?

The Duke of N——k so much admired the magnificent style in which "Triton" would spring into the strongest sea, that Lieut. P——d gave the fine animal to his Grace, who, for all I know to the contrary, still possesses him. (127-128)

The chapter "Anecdotes of Dogs on Service Abroad" contains two more Newfoundland anecdotes, both of which are illustrated:

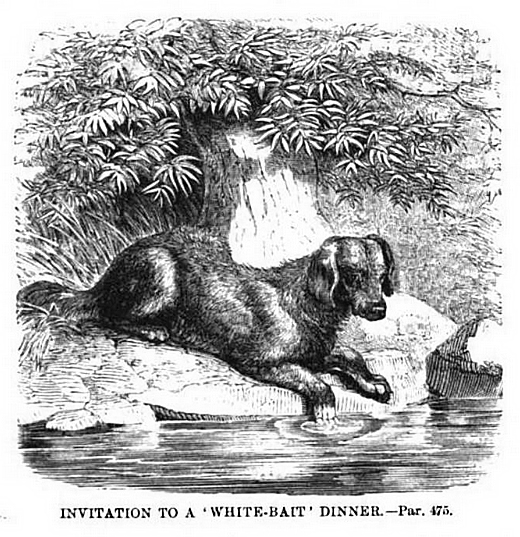

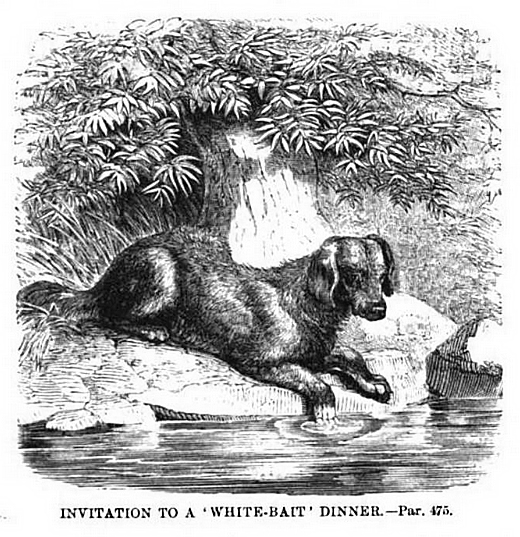

. . . I have now in my mind an instance of sagacity in a Newfoundland, apparently so much less entitled to credence, that I should be afraid to tell it (though the breed is justly celebrated for its remarkable docility and intelligence), if its truth could not be vouced for by Capt. L&md—n, one of the best officers in the navy; and who, when I had the gratification of sailing with him, commanded that noble ship the "Vengeance."

At certain seasons of the year the streams in some parts of North America, not far from the coast, are filled with fish to an extent you could scarcely believe, unless you had witnessed it — and now comes the Munchausen story. A real Newfoundland, belonging to a farmer who lived near one of those streams, used at such times to keep the house well supplied with fish. He thus managed it — he was perfectly black, with the exception of a white fore-foot, and for hours together he would remain almost immovable on a small rock which projected into the stream, keeping his white foot hanging over the ledge as a lure to the fish. He remained so stationary that it acted as a very attractive bait; and whenever curiousity or hunger tempted any unwary fish to approach too close, the dog plunged in, seized his victim, and carried him off to the foot of a neighbouring tree; and on a successful day he would catch a great number. (267 - 268)

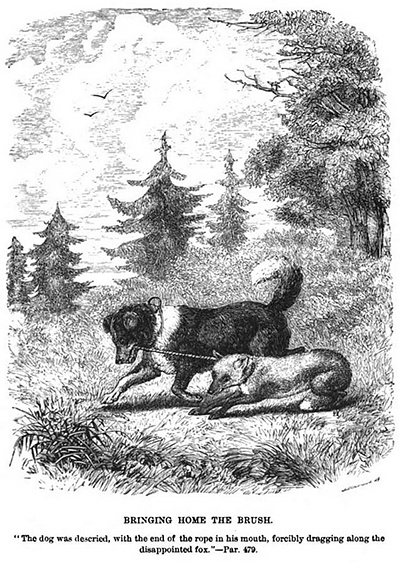

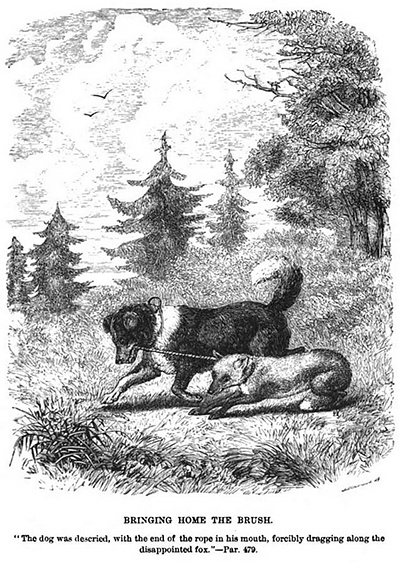

I have another anecdote of a young Newfoundland, told me by General Sir H——d D——s, to whose scientific attainments the two sister services, the army and the navy, are both so greatly indebted. He bred the dog in America, having most fortunately taken the dam from England; for to her address in swimming, and willingness to "fetch," he and his surviving shipwrecked companions were, under Providence, chiefly indebted for securing many pieces of salt pork that had drifted from the ill-fated vessel, and which constituted their principal food during their six weeks miserable detention on an uninhabited island.

At a station where he was afterwards quartered as a subaltern, in '98, not far from the falls of Niagra, the soldiers kept a tame fox. The animal's kennel was an old cask, to which he was attached by a long line and swivel. The Newfoundland and fox soon scraped an acquaintance, which, in due course, ripened into an intimacy.

One day that Sir H——d went to the barracks, not seeing anything of the fox, he gave the barrel a kick, saying to a man standing by, "Your fox is gone!" This sudden knock at the back door of his house so alarmed the sleeping inmate that he bolted forth with such violence as to snap the light cord. Off he ran. The soldiers felt assured that he would return, but Sir H——d, who closely watched the frightened animal, had the vexation of observing that he made direct for the woods.

Sir H——d bethought him to hie on Neptune after Reynard, on the chance of the friends coming back together in amicable converse. It would, however, appear that the attraction of kindred (more probably of freedom) had greater influence than the claims of friendship; for, instead of the Newfoundland's returning with Pug as a voluntary companion, after a time, to the surprise and delight of many spectators, the dog was descried, with the end of the rope in his mouth, forcibly dragging along the disappointed fox, who was struggling, manfully but fruitlessly, against a fresh introduction to his military quarters.

"Nep" was properly lauded and caressed for his sagacity; and Sir H——d was so satisfied that he would always fetch back the fox perfectly uninjured and unworried, however much excited in the chase, that the next day, after turning out Reynard, he permitted the officers to animate and halloo on the dog to their utmost. When slipped, though all eagerness for the fun in had, "Nep" took up the trail most accurately, hunted it correctly, and in due course, agreeably to his owner's predictions, dragged back the poor prisoner in triumph, having, as on the previous occasion, merely seized the extremity of the cord. (268)

There are no further mentions of Newfoundlands in this work.