[ Anonymous / The Sportsman's Repository ]

This book was first published in 1820; its sole reprinting was in 1845. Its title page bore the following full title: The Sportsman's Repository; Comprising a Series of Highly Finished Engravings, Representing the Horse and the Dog, in All their Varieties; by John Scott. From Original Paintings by Marshall, Reinagle, Gilpin, Stubbs, and Cooper: Accompanied with a Comprehensive Historical and Systematic Description of the Different Species of Each, Their Uses, Management, and Improvement; Interspersed with Anecdotes of the Most Celebrated Horses and Dogs, and Their Proprietors; Also, a Variety of Practical Information on Training and the Amusements of the Field.

The text below is taken from the 1845 edition published in London by Henry G. Bohn (York Street, Covent Garden). This latter edition also reprints the title page from the first edition (published in London by Sherwood, Gilbert, and Piper), which titles the work The Sportsman's Repository; or, the Correct Delineation of the Horse and Dog.

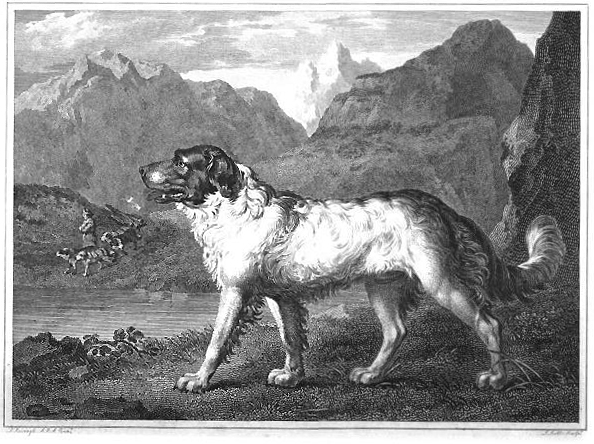

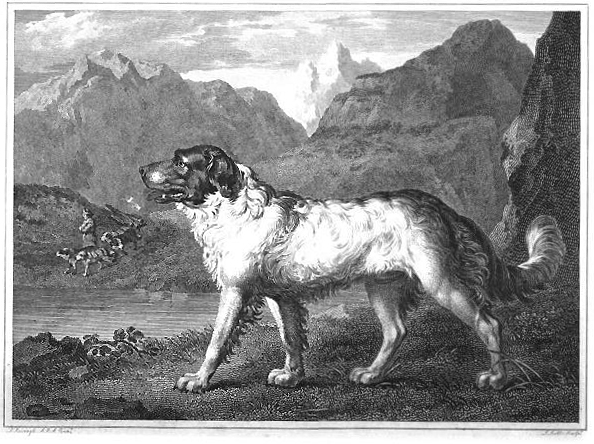

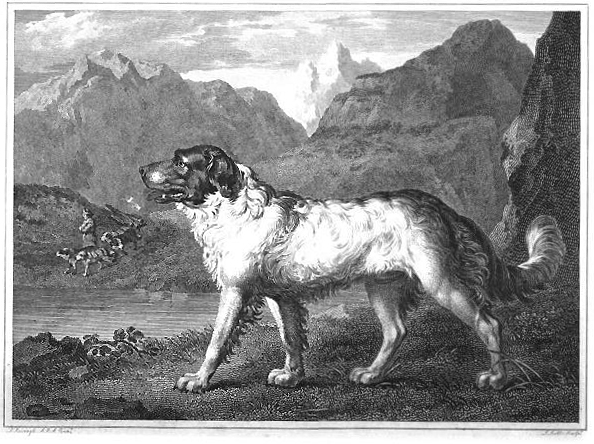

The images in this book (that of the Newfoundland is based on an earlier painting by Philip Reinagle) were engraved by John Scott (1774 - 1827), a noted English engraver and printmaker. His name did not appear on the title page of the first edition in 1820 — that edition was entitled The Sportsman's Repository, or a Correct Delineation of the Horse and Dog, with no byline, so the 2nd edition may well have included Scott's name in an attempt to trade on his reputation as an engraver.

The first mention of Newfoundlands in a context probably somewhat surprising to modern-day Newf owners:

Our present races of Sporting Dogs are thus distinguished and denominated — Hounds — The Bloodhound, Stag and Buck Hound, Greyhound, Fox Hound, Terrier, Beagle, Harrier, and Lurcher. Gun Dogs — The Pointer and Setter, Land and Water Spaniel, The Newfoundland Dog and Poodle. (p. 55)

The author mentions the Newfoundland next in connection with a favorite idea of his, the "decay" of the original English Mastiff:

"...the breed of the original Mastiff or Ban Dog of this Country, has been for many years almost or entirely worn out. Should any Gentleman be desirous to recover and increase this ancient breed, he has only to procure a male, as nearly as possible of the old form and qualifications, and graft him on any proper stock, with respect to size; a Newfoundland Bitch for instance." (p. 57)

There's also this casual mention:

Of all the various Species, there are none of which so many stories have been related of sagacity, fidelity and attachment to human nature, as of the Newfoundland and the Shepherd's Dog; some of these are well authenticated. (p. 101)

And another mention which refers to the image reproduced below:

The annexed Plate presents the truest possible representation of the original Water Dog of the opposite Continent [i.e., North America], long since adopted in this Country; in some of the maritime districts still preserved in a state of purity, but the breed more generally intermixed with the Water Spaniel and Newfoundland Dog. (p. 111)

The main entry on the Newfoundland is found on pp 133 - 138. It begins with an illustration, reproduced below, which is the image — engraved by Scott from a painting by Philip Reinagle — that graced the 1803 publication The Sportsman's Cabinet (treated separately here at The Cultured Newf). There is also a tailpiece image, reproduced at the end of the entry. The final paragraphs of this entry discuss a "Russian Dog" and its role in a legal dispute, but those paragraphs are retained because (1) they are included by the author as an illustration of the qualities and character of Newfoundland dogs; and (2) the "Russian" dog sounds very much like a Landseer.

THE NEWFOUNDLAND DOG

THE NEWFOUNDLAND DOG is of the largest Arctic breed, that is to say, of that of the Northern frozen Climes. In the head, countenance, and pendulous ears, he resembles both the hound and the spaniel, and in his nature, partakes of the qualities of both. He has the long shaggy hair and web feet of the water dog, and may indeed be almost pronounced amphibious, no other of the canine race being able to endure the water so long, or swim with so great facility and power. His tail is curled or fringed, and his fore legs and hinder thighs are also fringed. The Portrait here given, we understand to have been taken from the life, the dog being a real native of Newfoundland, imported for a Gentleman, by the late Mr. Brooks, of the New Road, London. This dog, although not so tall as the Irish Greyhound, is, in respect to the size of his bones, and weight of his carcase, perhaps the largest of the whole race. He is not at all remarkable for symmetry in his form, or in the setting on of his legs, whence his progression is somewhat awkward and loose, and by consequence, he is not distinguished for speed; a defect which might be remedied in breeding, were an improvement, in that particular, desirable.

No risk is incurred by pronouncing this dog the most useful of the whole canine race, as far as hitherto known, upon the face of the earth. His powers, both of body and of intellect, are unequalled, and he seems to have been created with an unconquerable disposition to make the most benevolent use of those powers. His services are voluntary, ardent, incessant, and his attachment and obedience to man, natural and without bounds. The benignity of his countenance is a true index of his disposition, and nature has been so partial to this paragon of dogs, that while he seems to be free from their usual enmities and quarrelsomeness, he is endowed with most heroic degree of courage, whether to resent an insult, or to defend, to his last gasp, his master or companion when in danger. His sagacity likewise, surpasses belief, as do the numerous and important services rendered to society, by this invaluable race, in lives saved, persons defended, and goods recovered, which by no other possible means could have been recovered. The list of his qualifications is extensive indeed: he is one of the ablest, hardiest, and most useful of draught dogs; as a keeper or defender of the house, he is far more intelligent, more powerful, and more depended upon, than the Mastiff, and has been frequently of late years substituted for him, in England, indeed, may with much propriety, entirely supersede that breed, the old Ban Dog being now nearly or entirely worn out. As a Water Dog, and for his services upon navigable Rivers, none can come in competition with the Newfoundland; and various Sportsmen have introduced him into the field, and shot to him with great success, his naturally kind disposition, and great sagacity, rendering bis training an easy task. The usual fate attends this generous race, among us, they are too often degraded and deteriorated by inferior crosses; one piece of good fortune however attends them, they are not, in this Country, bred beyond the demand, thence, we do not, with respect to them, witness the disgusting sight of abandonment and starvation in the streets.

This race has been known in England, and we suppose likewise upon the Continent, beyond living memory, and has been upon the increase amongst us, for the last twenty or thirty years. They were most probably introduced into this Country, soon after the discovery, at least colonization of Newfoundland, to which, and to the neighbouring Continent, they are indigenous, and at present sufficiently numerous, in their original and uncrossed state. These dogs about seven years since, were computed to amount to upwards of two thousand, at, and in the vicinity of St. John's, Newfoundland. They are there, by selfish and inhuman custom, left during the whole summer, whilst their Proprietors are engaged in the Fishery, to shift for themselves, and are not only troublesome and dangerous to the resident inhabitants, but also public nuisances in the streets, from starvation and disease. Contrary to their natural disposition, when associated with and supported by man, and goaded by the imperious demands of hunger, they assemble in packs, prowl about like wolves for their prey, destroying sheep, poultry, and every thing eatable within their reach. On the return of the Winter season, and of their masters from fishing, these last unfeeling two legged animals, seek with the utmost eagerness, their lately abandoned dogs, without the assistance of which, it would be absolutely impossible to get through the severe labours of a Newfoundland winter. In seeking and claiming these dogs, much confusion, and even litigation in the Courts, ensue, the value of these periodically deserted animals, being estimated at between two and eight pounds each. They are constantly employed throughout the winter, to draw wood cut for fuel, from the Country to St. John's, fish from the shore, and all kinds of merchandize from one part of the town to the other, to the amount of many hundred pounds worth in a day. It is asserted that, in one month, the year 1815, these Dogs furnished the town with from nine hundred to one thousand pounds value per day, and that a single dog, will by his labour, support his owner throughout the winter.

In the above year, a dangerous disease, supposed to be rabies, seized the Dogs at St. John's, and this was attributed to the bite of a Bull dog from England, but in far greater probability, all circumstances considered, the disease originated in the neglect and starvation to which the animals had been subjected in the summer season. This opinion, in fact, received a double confirmation: many persons were bitten, but in the course of some months, no symptoms of rabies appeared, and farther, an experienced medical Gentleman, who had passed seventeen years in Newfoundland, observed during almost every season, symptoms nearly resembling the present, and had even a number of patients who had been bitten, one in particular, thirteen years since, bitten in his presence by a dog, which he was convinced at the time, was really rabid; he treated the case, however, as a common wound, no ill consequences ensued, and from general concurrent testimony, no such disease as canine madness had existed in the Island, which yet he acknowledges might possibly be imported in dogs from Europe. Here a most important consideration suggests itself, and would be acted upon with the utmost punctuality, did men think their dearest interest worth the trouble of a guard. Is the good fortune light or trivial, to be exempted in their own persons and dearest connections, from the most horrible of all human inflictions, CANINE MADNESS and hydrophobia? A Country surely ought to be deemed most fortunate from such exemption, and every possible care ought to be used, to prevent the intrusion of foreign dogs, more especially into Newfoundland, which possesses within itself, the best breed upon earth, for every possible use or purpose in that country.

The Gentleman above alluded to, attributes the disease which had the semblance of real madness, to a fever induced by severe labour, with insufficient nourishment, from salt and improper food, and hard comfortless lodging. Materially also, to the want of a sufficiency of water, the streams being frozen, and the wretched dogs being reduced to the necessity of barely moistening their mouths with snow; and even while water is plenty, their unfeeling task-masters, will not allow the animals, by the exhausting labour of which they are supported, time to slake their thirst, although, in that respect, they are always extremely complaisant to themselves! That which renders the neglect still more cruel and abhorrent from true feeling, is, these victims of human selfishness, actually starved when their services are not wanted, have no other food during their daily labour, than damaged and putrid salt fish! In the mother Country, although the animals are neglected and ill treated to a degree sufficiently reprehensible, we have nothing of equal infamy, but it is an opinion of long standing, that in Colonies, every branch of morality is universally at a low ebb. Of this, the following sentiment, in the letter from which our account is derived, is a tolerably sufficient proof — “It is certainly fortunate, there is such a disorder, as unless there was something of the kind to carry off the dogs, we should be overrun with them.” As if it would not be more profitable, as well as humane, to prevent, in the first instance, a surplus of these indispensable dogs; or in the second, to dispose of the surplus in a manner more consistent with justice and compassion — and of what far greater profit would the animals be, judiciously reduced in numbers, and kept in good condition.

In February 1815, the Grand Jurors of St. John's, presented to the Court of Session, the existing state of the Dogs in the town, supposed to be hydrophobia, as dangerous to the inhabitants; and it was, in consequence, ordered that, all dogs found at large, in or about the town of St. John, be forthwith destroyed excepting such as are employed in Steds, being securely muzzled: and that, in order the more effectually to promote the destroying such dogs, a reward of five shillings, for every such dog destroyed, should be paid, upon its being produced in the Court House yard.

Since the commencement of this article, a correspondent has obliged us with the following particulars relative to a Russian Dog, late the property of his friend Mr. Mudford. These Gentlemen belong to that class, who think it no derogation to humanity, to feel and shew compassion to the animal creation, and affection to that part of it, which is so highly meritorious from its attachment and services. Unhappily, there are men of a totally opposite description of feeling, who view the whole brute creation with a sullen apathy, through the medium only of coldhearted interest; who are dead to their caresses or their merits, and who, on every occasion, are prone to trea tthem with a dastardly barbarity. Children aretoooften thus naturally inclined, or too apt to imbibe from example, this malign disposition, the counteraction of which is a necessary branch of morality. The reader will presently find an example of these truths, both adult and infantine; and also a practical exemplification of the character which we have given of the Newfoundland Dog.

The story, in brief, is, Mr. Mudford had a young Russian Dog, named Crop, of the same Northern species, and similar qualifications with the Newfoundland. He was in colour black and white, his hair nine inches in length, and of a beautiful and commanding figure, attractive and interesting to all spectators. He was distinguished by those peculiar and noble characteristics, to which we have already adverted, in this species, and the union of which in the same individual animal, seems almost incompatible, the highest degree of courage and even fierceness on necessary occasions, and the most endearing and playful good-nature and inoffensiveness: to these were joined, which we have also before described, an incessant disposition to volunteer his services, wherever his extraordinary sagacity pointed them out, as necessary or useful. A remarkable instance of this, in Crop, was, his noticing the habit in his master, of being accommodated with his boot jack, slippers, and morning gown, on returning home in the evening. On a certain evening, while Mr. Mudford was waiting for these, a lumberiug noise was heard upon the stairs, when suddenly, to the astonishment of himself and family, Crop entered the room with the gown, which having laid at his master's feet, he set off again, and returned with the boot jack and slippers, depositing them also, and expressing in his motions and countenance, the satisfaction he enjoyed at having rendered a service. He ever after performed the office of Valet de Chambre, not only to his master, but if a visitor happened to arrive late in the evening, he always brought him the boot-jack, and slippers. Crop, as well as a caressing, was a kissing animal, and would kiss any person who desired him ; and his natural instinct approximated so nearly to human reason, and his affection for the human race was so great, that, the opinion given by a certain literary lady, of a dog of the same species, seems equally applicable to Crop—he can be no other than some benignant human being transformed into a dog, by one of those Enchanters celebrated in the Arabian Nights.

The owner of this most valuable animal, lost him through the malice and cowardice of his neighbour, an Italian; and although well aware of the exhorbitant price which justice bears in our legal market, deterring so many from becoming purchasers, he resolutely and meritoriously determined to seek his remedy; and, as will be seen by the account of the trial, gained his cause, by which, with Teague of old, he gained a loss; as defendant, on losing his cause, instantly made himself scarce, leaving Plaintiff to stand Captain for costs and damages, who thereby verified the old English proverb on sueing a beggar.

MUDFORD versus DU RIEU.

K. B. —July 17, 1816. —Sittings after Term. This was an action brought by Mr.Mudford, a literary Gentleman then residing at Somers' Town, against the Defendant, to recover compensation in damages, for the loss of a dog which was wilfully shot by the Defendant.

Mr. Topping, for the Plaintiff, addressing the Jury, stated that, the Dog in question was a most beautiful animal of the Russian breed, perfectly docile and good humored, but like all dogs of his age, being but fifteen months old, was playful and wild. From a puppy, not a single instance had occurred, in which it had either bitten or attempted to bite any person whomsoever. The Defendant's Children nevertheless had thought proper, on various occasions, to teaze the animal by beating him with boxing gloves, thereby occasioning him to bark at them, yet never, on any occasion, attemping to bite them. His barking, however, had produced, either an actual or a fictitious alarm, on the part of the children; and the Defendant, in consequence, at one time, when passing the animal, gave him a violent kick, threatening at the same time, if he should ever catch him in the field, he would shoot him. Under apprehension of this threat, the Plaintiff had given directions, that the dog should be confined within doors; and he was so confined for ten days, previous to the 6th of July, 1815, when the door being accidentally left open, he ran into the yard, and leaping over the wall into the field, he expressed his joy at the recovery of his liberty, by loud barking and running about from place to place. Mrs. Mudford, the Plaintiff's sister, and the servant, immediately went out in order to catch him, but their efforts, from the playfulness of the animal, were ineffectual. While they were thus engaged, the Defendant's daughter came out, accompanied by a female companion, and approaching the dog, the former took up a brick, saying, if the animal came nearer she would beat out his brains. The dog did run nearer but never attempted to touch her, continuing his gambols with perfect indifference to every person. The Defendant's wife now came out, and called to her husband, for heaven's sake to bring out his pistols. At the same time she went towards the dog, with her infant son, about four years old – no proof of apprehension on her part – and put the child towards the animal's mouth, but it did not offer to bite: she however, as if by previous concert, immediately cried out, oh! my child! and drew it away. The child, alarmed at the barking of the dog, shrieked, upon which the Defendant came out with a pistol under his coat. By this time the dog had reached his master's wall, and Mrs. Mudford was pulling him down by the neck, when the Defendant drew forth his pistol, and shot the animal in the loins, and wounded him so, that he died in a very short time.

With respect to the value of the animal, the learned counsel said, that he should be enabled to prove that the Plaintiff had been offered a very large sum for him, and that he was possessed of many of those acquirements which render a dog valuable, such as fetching and carrying his master's clothes and slippers, with an uncommon attachment to all the family, and the most perfect good-nature to all who treated him with kindness. Witnesses were then called in support of this case. Mrs. Elizabeth Whiting, the Plaintiffs sister, proved the docility and playfulness of the dog, but positively denied that it had ever bitten, or attempted to bite, any person. Her brother had been offered fifteen guineas for the dog a short time before the day on which it was shot. On that day it accidentally escaped from the confinement, in which it had been held, in consequence of the threats of the Defendant. It never attempted to bite the Defendant, or his children, although often provoked by the latter, and kicked by the former. This evidence was supported by three other witnesses.

The Attorney-General addressed the Court and Jury on the part of the Defendant, and contended that, in this instance, his client was perfectly justified in the course he had taken, for that he had shot the dog in his own defence. The dog had twice jumped at him, and he had beaten him off; he was jumping at him a third time, when he fired and thereby prevented the consequence, which might otherwise have accrued to himself. In proof of this, as well as in support of the case of the Defendant, in general, four witnesses appeared, who stated that, the Defendant was called into the field, by the screams of his daughter, and that in shooting the dog, he acted in his own defence. In the evidence of these persons, however, there was so much prevarication that the Jury, after an impartial and able charge from Mr. Justice Abbott, found a verdict for the Plaintiff—damages, fifteen guineas—costs forty shillings.

It may be useful to record the law, as laid down by the present Lord Chief Justice, on this trial. He stated distinctly, that the only justification for a man shooting the dog of another, is the necessity of self-defence; but that necessity must be clear and positive. If, he observed, a man were attacked by a dog, and while the dog was making the attack, he killed him, he would act legally; but if he killed the dog while it was running away from him, after having so attacked him, the owner of the dog would be entitled to recover his value. The reason of this distinction, he said, was clear. In the first case, self-defence justified the killing of the dog; but in the second, it did not — for the dog had himself retired from the attack, and the party aggrieved ought then to seek his remedy for whatever injury he may have sustained, at the hands of the owner of the dog.

Newfoundlands are also mentioned significantly in the discussion of "Arctic or Greenland" dogs:

From the portrait of the [Arctic] Dog in the Magazine above cited [Sporting Magazine of January 1819], he would appear to be a smaller variety of the Arctic species, than those commonly used in draught, and it may be conjectured that such smaller variety may originate in a Fox cross, as the largest may probably in that of the Wolf. A Writer in the Magazine, seems to confound the Greenland Dog, with that called the Newfoundland, which has been imported from thence, and from the neighbouring court of Labrador, where the Esquimaux, inhabitants of that Country, use them for draught and for hunting. There are however, as we before stated, varieties of the same species, that of Newfoundland having longer hair, and pendulous ears, which is generally, in animals, an indication of large size.

On discrimination between the two races, a Medical Gentleman, long resident on one of our Settlements in Hudson's Buy, offers the following remarks. "The Dog from Newfoundland, may have reached the Arctic Regions, and vice versa — but the Arctic Dog is made truss [sic] and deep: the original one of Newfoundland loose and lengthy; the former has pricked ears, a bushy tail, and deep russet coat, and without any extra cause of animation, looks always ready for a start. The latter has a fine lopped ear, and a very full tail, which, when erect and doubling over his back, boasts the richness of the most luxuriant Ostrich feathers. His colour is dingy black, or black and white, seldom russet, never liver-coloured; moreover, when not in action, the Newfoundland Dog is the most sleepy and most lazy of the canine species."

The two breeds agree generally, in regard to qualities, with some exceptions. Like the Bull Dog, they seldom or never bark, their vociferation being rather snarling and howling. On this point, the Rev. Mr. Asnach, in his History of Newfoundland, has the following observations. The Newfoundland Dog seldom barks, and only when strongly provoked; it then appears like an unnatural and painful exertion,which produces a noise between barking and howling, longer and louder than a snarl, and more hollow and less sharp than barking, still strictly corresponding to the sounds expressed by the familiar words bow wow; and here he stops, unless it ends in a howl, in which he will instantaneously be joined by all the dogs within hearing. This happens frequently, and, in a calm, still night, produces a noise particularly hideous.

The same Author describes the Newfoundland Dog, in one most important respect, very different to what we find him in this Country, an implacable enemy to sheep; which ought to suggest a strong caution to those, who keep or breed these dogs. As a proof, Mr. Asnach gives the following incident. He had three young sheep, for which, in the day-time, his dog affected the utmost indifference: the servant, however, having one evening neglected to secure them in their shed, and to confine the dog, the sheep were found in the morning, stretched out lifeless, without any other mark of violence than a small wound in the throat, from which the dog had sucked their blood. It is remarkable that, the Newfoundland Dog, when pursuing a flock of sheep, will single out one, and, if not prevented, which is a matter of considerable difficulty, will never leave off the pursuit, until he has mastered his intended victim, always aiming at the throat, and after having sucked the blood, has never been known to touch the carcase.

Farther very interesting particulars are given of this dog, both of his natural merits and demerits; his sagacity, courage, and gentleness, his ferocity, and treachery. The docility of this superior race being one of their most eminent qualities, good training, and familiarity with human customs only, are needed to render them perfect in their kind. The above dog had been purchased when a puppy, from the Northernmost part of the Island, was of the pure Newfoundland breed, and grew up to the size of a small donkey. He was well calculated for hard labour, exceedingly tractable and gentle, shewing a particular attachment to the children of the family, and agreeing perfectly well with the cats, which he treated with a kind of dignified condescension, as animals which nature had placed in a sphere far below his. He was, in general, very easy to please in the quality of bis food, being contented with scraps of boiled fish, fresh or salted, with vegetables, potatoes or cabbage. So much however of his wild nature remained stirring in him, that if hungry, he never scrupled to rob the larder, when unguarded, of either fish or flesh, and had a bowel-hankering after the larger kind of poultry, the blood of sheep yet being his most favourite nourishment.

Jowler, such was his name, would chase sheep wherever he could find them unguarded, even from high cliffs into the sea, and jump in after them: not, however, without first estimating the elevation of the cliff, which finding too great, he would run down and take a more convenient rout for pursuit. His master had domesticated some wild Geese, one of which would frequently follow him in his morning walks, side by side with Jowler, the two apparently living together on the best terms. Unfortunately the servant one night neglected to confine them, according to custom, and the next morning the feathers of the favourite goose were found scattered in a small field adjoining to the grounds. The dog was soon after found concealed in the corner of a wood-yard, and on his master looking at him, exhibited evident signs of conscious guilt. His master took him to the field, and pointed out to him the poor goose's feathers; on which the dog staring at him, uttered a loud growl, and ran away at full speed; nor could he endure his master's sight for some days afterwards.

The Greenland Dog is described as naturally timorous, perhaps shy, and not so easy to domesticate as the Newfoundland, which latter is said never to exhibit any signs of timidity. The dog Jowler, after many hard fought battles, and when he had attained his full growth, soon established his character for superiority. He was not quarrelsome, but treated the smaller species of dogs with patience and forbearance; but when attacked by a dog of equal size, or engaged in restoring peace among other dogs, he would set to, most vigorously, and continue the struggle until submission was obtained, or peace completely re-established. He would then leave the field of battle with a haughty look, and a warning growl, and be afterwards as quiet as a lamb. His master was perfectly secure in his company; for the least appearance of an attack on his person, raised at once the dog's attention, and produced a most tremendous growl as the signal of action, in his master's defence. The sagacity of this animal was astonishing, and on all occasions he seemed to want only the faculty of speech, to place his intellect on a level with the human. The character indeed of Jowler seems much to resemble that of Savages, who, however mild and good their dispositions rriay naturally be, yet cannot on their first intercourse with civilized men, repress their thievish propensities.

C. Garland, Esq. a Magistrate, who died a few years since near St. John's, Newfoundland, had a dog, which used to carry the lanthorn before him, by night, as steadily as the most attentive servant, stopping when his master stopped, and proceeding when he saw his master disposed to go on. When Mr. Garland was out, by night, this dog, the lanthorn being fixed to his mouth, and the command given, 'go fetch your master,' would set off and proceed directly to the town, which was about a mile distant, where he would stop at the door of every house which he knew his master frequented, and laying down his lanthorn, growl and strike the door with his foot, making all the noise in his power, until the door was opened. Not finding his Master there, he would proceed farther, in the same manner, until he found him. If he had only accompanied his Master once into a house it was sufficient to induce him to take that house in his round.

The next reference to Newfoundlands occurs in the discussion of the English mastiff, a breed which the author of this book feels has been allowed to lose much of its original character and utility:

It might be deemed extraordinary, did not things upon a level in point of common sense, often occur, that no one, dealer, sportsman, or other, should find it worth while, to preserve the so-long-famed breed of the English Mastiff in its original purity, and that we should prefer the execrable and useless race of the Bull Dog. So it has happened however, and if there be any true bred Mastiffs left in the Country, they must need be things to be far fetched and dear bought. So we found it, many years ago, when we purchased one at a considerable price, as a guard in a lonely situation. If size and kindness of nature alone, had constituted the Mastiff, we had been suited to perfection; but as a guard, the dog was of no kind of use, having no faculty to make distinction between friends and foes, but ready at all times, to associate and shake hands with all men. We were sorry to part with this jolly and good-natured animal, but he was too expensive for a useless inmate. What, in fine however, ought to diminish our regret at the loss of the old English Mastiff, is, as we have before observed, the satisfactory substitution of the Newfoundland Dog; a race which merits to be kept pure, and free from our silly and boyish propensity to crossing of breeds. (161)

(How a Newfoundland should prove a "satisfactory substitution" for a mastiff that's useless as a guard dog because it loves everybody is beyond me.)

The next reference to Newfs also occurs in the discussion of Mastiffs:

The following remarkable example of canine sagacity, was said at the time to be well authenticated. In the Autumn of the year before the last (1818,) a Lady walking over Lansdown, near Bath, was overtaken by a large Mastiff dog, which had just left two men, who were travelling the same road, with a horse and cart. The dog continued to follow the Lady, at the same time endeavouring to make her sensible of something, which he could not otherwise express, by looking in her face, and then pointing behind with his nose. Failing to make himself understood, he next placed himself so completely in front of the object of his solicitude, as to prevent her proceeding, still looking stedfastly in her face. The Lady became somewhat alarmed; but judging from the manner of the dog, which did not appear vicious, or to have any mischief in view, that something about her person must have engaged his attention, she examined her dress, and missed her laced shawl. The dog perceiving that he was at length understood, immediately turned back: the Lady followed him, and was conducted by him, to the spot where her shawl laid—some distance back in the road. On her taking it up, and replacing it on her person, this interesting quadruped immediately ran off at full speed, after his master, apparently much delighted at the service he had rendered; leaving the Lady in a state of astonishment, which did not permit her at the instant, to reward her benefactor with those caresses which he so highly merited.

Most probably, this dog, in the above relation, called a Mastiff, was chiefly of the Newfoundland breed, a mastiff-substitute, the entire Mastiff not being remarked for the qualities here described. We embrace this opportunity to acknowledge, that the Portrait which we exhibit of the Mastiff, must not be considered as a specimen of the pure original race — for where could our Artist find one of that description? but of the Mastiffs or large Yard Dogs of the present time. This portrait, which was from the life, obviously shews a hound cross — a portion of the old Mastiff, joined with the Blood Hound or Southern Hound.