[ Fuertes, Baynes, et al / The Book of Dogs ]

The title page of this work attributes authorship to "Louis Agassiz Fuertes and Others"

Fuertes (1874 - 1927) was an American ornithologist and illustrator, one of the most well-known and respected illustrators of his time, sometimes compared to the great John James Audubon. It's probably for that reason that Fuertes is credited as the principal "author" of this work; the title page goes on to note that the book is "Illustrated with 73 Natural Color Portraits from Original Paintings by Louis Agassiz Fuertes," although Fuertes did also write or co-write some of the text.

Much of the text was written by Ernest Harold Baynes (1868 - 1925), a well-known American naturalist and writer on natural history subjects, known for his habit of allowing various wild creatures to wander through his house. He was also known for his staunch defense of vivisection.

The Book of Dogs; an Intimate Study of Mankind's Best Friend was first published in 1919 by the National Geographic Society (Washington DC), and was reprinted in 1927. The text below is taken from the 1919 edition.

This work mentions Newfoundlands a number of times, the first being in passing, in a section remarking on the diverity of dog breed types:

Compare a Newfoundland or, better still, an Eskimo dog, whose thick, dense coat can withstand even the rigors of an Arctic winter, with a hairless dog of Mexico or Africa, which looks cold even in the middle of summer. (6)

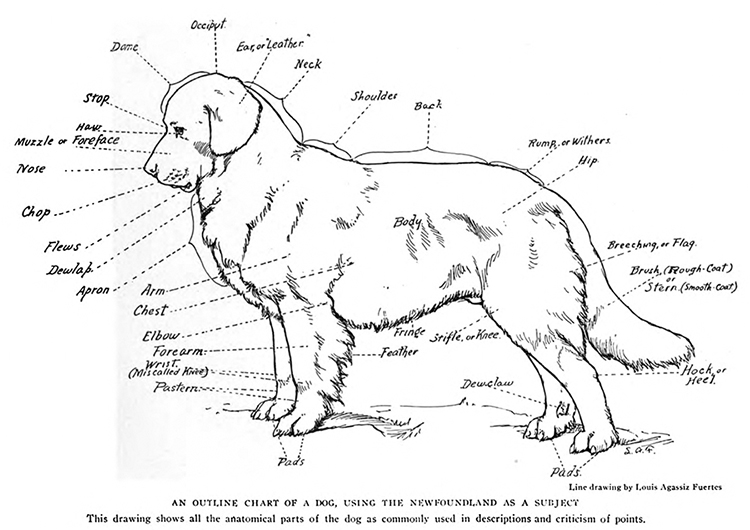

Newfoundlands show up next as a diagram used to illustrate the various body parts of dogs (16):

click the image to open a larger version in a new tab/window

In keeping with other similar comments from the early years of the 20th Century (see, for example, this article from The Dog Fancier magazine, which will lead you to others that make a similar point), a footnote in the chapter entitled "Our Common Dogs" (co-written by Fuertes and Baynes, though the footnote appears to be by Fuertes alone) notes that "it was impossible to get modern material on such dogs as the Newfoundland and pug, no longer extensively bred, as their day of grace is done." (fn, 20)

This theme of the "disappearing Newfoundland" is repeated in the breed entry on the Newfoundland; note that some of the text refers to Newfs in the past tense, as though the breed were already lost:

Two dogs which rival the Eskimo in their ability to endure deep snow and extreme cold are the St. Bernard and the Newfoundland, both of which have become famous as savers of life. Both are well-known subjects of the poet and the painter, who delight to record their heroic deeds or their simple fidelity.

(this image is not in the original text;

click image for more on Newfoundland stamps)

The Newfoundland has the further unique distinction among dogs of being figured on a postage stamp of his native land. He is a wonderful swimmer and is credited with saving many people from drowning.

It is a real pity that this noble, useful, and typically American dog should have lost popularity to such an extent that now he is almost never seen. Only two strains are preserved, so far as can be learned — one in England and one in New Jersey. Therefore it was a great pleasure as well as a great assistance in the making of the plate to meet face to face at the Westminster show of 1918 the straight descendant of the very dog whose photograph had been the artist's model.

The magnificent St. Bernard carries on better than any other breed the qualities that characterize the Newfoundland. For many years the breed, which had been perfected and stabilized in England, was used as a farmer's helper, having the intelligence needed for a herding dog and the weight and willingness to churn and do other real work.

His benignity and unquestioned gentleness made him a very desirable guard and companion for children, and his deep voie rather than his actual attack was usually a sufficient alarm against unwonted intrustions. Aside from these fine qualities, however, his mere beauty and staunch dependability should have been sufficient to preserve him from the fate that seems to be almost accomplished.

Weighing from 120 to 150 pounds and standing 25 to 27 inches at the shoulder, the deep-furred, massive-headed, and kind-eyed Newfoundland was one of the most impressive of dogs. He was strong, active, and leonine both in looks and in action, having a rolling, loosely knit gait. There were two recognized colors — all black (white toes and breast spot were not defects, however) and white, with large black patches over the ears and eyes and on the body, the latter being known as Landseer Newfoundlands, because a dog of this type is the subject of Sir Edwin Landseer's well-known painting "A Distinguished Member of the Humane Society." The forehead was domes almost to the point of looking unnatural; the broad forehead, deep jaw, flews, and dewlaps betokened a kind and gentle nature. (37, 40)

The Newfoundland entry was accompanied by the following Agassiz painting:

Newfoundlands are referred to twice more in this work, both times in passing. In the breed entry for St. Bernards, we are told "the dogs used by the monks have changed greatly in appearance from time to time. Occasionaly [sic] an avalanche will destroy a large number, and those remaining will be bred to Newfoundlands, Pyrenean sheep dogs, and others having similar characteristics" (44).

Newfs are last mentioned in the chapter entitled "The Sagacity and Courage of Dogs," though surprisingly this chapter offers no anecdotes regarding the presence of those traits in the Newfoundland. Newfs are mentioned only when the authors remark that other writers "have contrasted the bare-skinned, pocket-sized Chihuahua with the rough-coated, masive-built Newfoundland" (69).

For other works that comment on the declining prevalence of Newfoundlands both in Newfoundland and in the dog world in general, see "The Disappearing Newf" here at The Cultured Newf.