[ Dogdom ]

A monthly American magazine (Battle Creek, Michigan), edited by F. E. Bechmann, devoted "Exclusively to Dogs, Dog Fanciers, Bench Shows, and Field Trials." Early 20th Century.

The September, 1917, issue's "Dogs of the World" column, by Freeman Lloyd, was devoted to the Newfoundland, and begins by contributing to the slew of articles and books which lament the (relative) disappearance of the Newfoundland in the early 20th Century:

It is passing strange that the dog of Newfoundland, at the present time, is extremely scarce in the United States. A few years ago we used to see at least one good specimen at the W. K. C. show in Madison Square Garden, New York, but, lately, the beautiful Newfoundland appears to have passed away altogether. About three years ago a person living in Greenwich Village, New York, imported two or three, but they were used for advertising purposes, and as far as is known were not exhibited, although one of them was quite a good specimen. In these days when so many people live in apartments the good times of the larger breeds appear to be over; but the Newfound!ami must always remain in our thoughts as one of a most noble of God's creatures.

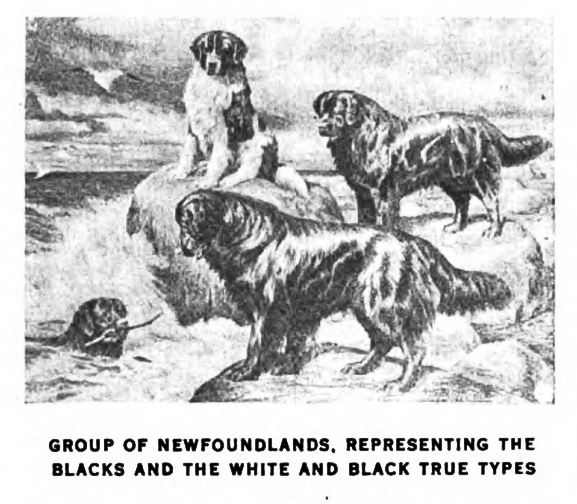

Of all dogs, perhaps, the Newfoundland is most associated with what we connect with great sagacity, enoroums power and untold charity of character. He is as brave as he is mighty, and his peculiar common sense and memory are among the essentials embodied in that great carcass of dog flesh covered with a coat of black or of white and black. The self-colored or wholly black dog was at one time looked upon as the most typical by breeders, but when Sir Edwin Landseer's picture, "A Distinguished Member of the Humane Society" (which represented a white and black Newfoundland lying on a quay), became known, the heart of the whole world went out to dogs of that kind. Perhaps there never was a painting more engraved and copied than this masterpiece of the great artist; and wherever we may go, where civilization is to be found, there may we, with renewed and never ending pleasure, gaze upon the great animal painter's Newfoundland. Strange though it must appear, some of the leading breeders of Newfoundlands are of the opinion that the picture in question has accomplished more harm for the breed than otherwise, since it gives to the universe rather an erroneous idea as to what a true Newfoundland should be like. The Newfoundland dog, of course, takes his name from the island of that name, whilst the lesser Newfoundland, or Labrador dog, is now principally to be found as a pure variety or in different strains of smooth and wavy coated retrievers. The splendid watering capabilities of both varieties of the old colonial dogs, their sense of duty, benevolence in work and courage under all circumstances, fit them for the work of the sea, river, field and swamp.

That the Newfoundland dog is better out of Newfoundland than he is in it, there can be no doubt. As a rule he was a small dog at home as compared to the improved breed abroad, where outside crosses have been used and more attention given to his rearing. There may have been an introduction of St. Bernard blood. According to some people, when the stock or stud dogs of the Hospice of St. Bernard in the Alps were accidentally destroyed by an avalanche, a Newfoundland was used for crossing on to the bitches of the Hospice. Hence the Leonberg dog. The cross could be utilized the other way round and the probability is that greater size would be obtained. That St. Bernard's now and then have white and black puppies is within my own knowledge. Shortly before her death the late Miss Anna Marks, of South Beach, Conn., bred some St. Bernard's of the color mentioned from dogs and bitches of high pedigree. That would surely point to a Newfoundland-St. Bernard cross somewhere. Of course, they would be barred as Newfoundlands, but they certainly would have passed as white and black Newfoundlands.

One hundred and thirty years ago the dogs of Newfoundland were black and white in color, and previous to that they were brown or liver and white. It will be noticed I have differentiated between white and black and black and white. The predominating color is first given, as, indeed, it should always be when describing the ground color and the markings of an animal. All are agreed that a bronze tinge in the wholly black coat is in no way objectionable. This would point to the brown or liver ancestry; further, it should be remembered that black dogs from continued swimming in salt water become bronzed. In the self-colored dog a few white hairs on the chest will not disqualify a dog; neither will a white toe or two; it were better he should be wholly black.

A good many dogs arrived in England on sailing ships from the shores of the Northern Atlantic. Many years ago I remember spending an evening with the late Edwin Nichols, of West Kensington, London, and then the doyen of the Newfoundland dog world. His friend, Henry Irving, the actor, also used to like to have a chat on the breed. Mr. Nichols was certainly one of the most successful breeders of Newfoundlands of his time, and commenced to exhibit them in the early '60s. My dear old friend told me that he first became infatuated with Newfoundlands when he was quite a boy. He was born in Exeter, England, and sailing ships ladened with salt cod and lumber used to arrive at a port hard by and discharge their cargoes into lighters or "willy boys" to be taken up the Exe to the old and historic city. On these ships or lighters were generally Newfoundland dogs, the skippers being very proud of them. Most of them were trained to swim ashore with the end of a rope, and through a heavy sea. Thus, we will at once recognize that the dog was originally kept aboard craft to accomplish, in the event of stranding or any other service, a communication with those on land already apprised of some disaster or request by the booming of the ship's cannon or distress signal. The Newfoundland dog — always associated with life-saving — was able to manage what no poor mariner could attempt because of the breakers and terrible elements.

The late Mr. Nichols was, therefore, so impressed with Newfoundlands, generally, that he kept them to his dying day. And he had about the best. The Newfoundland dog should stand twenty-seven inches at the shoulder and the bitch twenty-five inches; the former weighing one hundred pounds and the latter eighty-five pounds. But I have seen much larger Newfoundlands, an occasional dog reaching thirty-two inches. Mr. Nichols' Lord Nelson was an enormous dog; he was classed, perhaps, by interested persons as a black St. Bernard. Still, there was some truth in the assertion, for the head of Lord Nelson was hardly that of the Newfoundland, which possesses a peculiar dome.

The coat of the breed under notice is most important. To be water and cold resisting, it must be straight, long and harsh. There is a wool or short, soft under-coat protecting the skin. When the Newfoundland shakes himself, after leaving the sea or river, he almost gets rid of all the moisture in one effort, and he is soon dry. In a heavy curly or wavy, soft-coated dog this would be different. The Newfoundland generally has enormous bone, and his legs, to his feet, are well feathered. His body is capacious, short and round, while his tail should be of moderate length, reaching a little below the hocks. A celebrated Newfoundland dog about the later '60s and early '70s in England was Cato, the property of the Rev. S. Atkinson. Not only was Cato an excellent example of the show dog of his breed, but he proved himself a life-saver, for off the Yorkshire coast in 1870 he was the means of pulling ashore his master and a lady whom Mr. Atkinson had gone out to rescue from being taken away by the current of the sea. There have been water trials for the breed, but they were not successful, possibly because of lack of management.

It is a very great pity that some one does not take up this magnificent breed in this country. There is ample and excellent stock from which to draw on the other side.

The excellent picture that illustrates this paper is a copy of the Diploma of the Continental Newfoundland Club (Europe's). (390 - 391)

The idea that the Newfoundland was a vanishing breed was touched on in a surprising number of magazine articles and books in the early years of the 20th Century. For discussion of the idea, see this article here at The Cultured Newf.

A follow-up to Lloyd's column was published in the October, 1917, issue of Dogdom. It was written by the Newfoundland breeder J. H. Clark, who had submitted several notes and photos regarding Newfs to this and other dog-related publications. Clark's response was titled "The Newfoundland in the United States":

In the September DOGDOM I see you have an article on the Newfoundland by Freeman Lloyd. A few extra words, with a photo or two, on the Newfoundland in the United States may interest some of your readers. I have owned Newfoundlands for thirty years, and at present have fifteen grown dogs and bitches. I have both imported and exported them, so you see I have done some permanent good for the grand old breed.

I know of at least seventeen Newfoundlands imported by six individual breeders in the last five years, to help improve and furnish new blood to some of the good stock we had. In every case, except one or two times, the onwers have not exhibited as they did not wish to risk bringing distemper or pneumonia to their kennels. The breeders I speak of are not looking for notoriety, and as they are all business men, have not the time, or at least do not take the time to let people know what they have. They have gradually distribued their surplus stock amongst their friends, and thus the public do not hear of their fine dogs. We have today just as fine specimens in the United States as can be found anywhere.

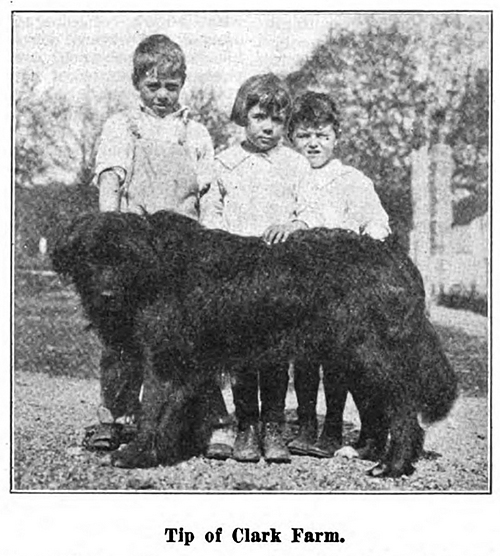

The photos of the two American-bred Newfoundlands, the black one, Tip of Clark Farm, and the Landseer, Lady Rebecca, show well the two colors. As per photo one may see they are the dogs for children, and as Mr. Lloyd says, "He is as brave as he is mighty, and his peculiar common sense and memory are among the essentials embodied in that great carcass of dog flesh covered with a coat of black or of white and black." — Josiah H. Clark, New York.

The two photos submitted by Clark followed his note; this photo of his Newfoundland "Tip" will also be published in The Dog Fancier of December, 1917.

Lady Rebecca, Newfoundland, also housed at J. H Clark's Kennels

Lady Rebecca, Newfoundland, also housed at J. H Clark's Kennels

It seems that Lloyd's column and Clark's follow-up prompted a contribution from another Newf-loving reader of Dogdom, for the January, 1918, issue contained the following note and photo:

Editor DOGDOM: I have been very much interested in the articles that have been appearing lately in DOGDOM on the Newfoundland. I have owned and imported these dogs for a number of years a nd enclose a picture of one of them I now have. I breed these dogs for my own pleasure, and I believe that the Newfoundland is the grandest breed of dogs in the world. Trusting to see more space in your magazine devoted to this breed, — Frank H. Moore, Woodfords, Maine. (670)