[ Watson / The Dog Book ]

James Watson (1845 - 1916) was a well-known Irish writer on canine subjects; he spent most of his adult life in America, and for a time served as editor of Field and Stream. An obituary for Watson appeared in the 1916 edition of the C. S. R. Blue Book of Dogdom which identified Watson as "one of the best known canine journalists in America and an old time breeder, judge, and writer.... Mr. Watson was without question the best writer on dog subjects in American and his works will always stand out as an authority." Watson claimed to be the person responsible for the name "Russian Wolfhound" for the breed now known as the Borzoi.

The full title of this multi-part work is The Dog Book: A Popular History of the Dog, with Practical Information as to Care and Management of House, Kennel, and Exhibition Dogs; and Descriptions of All the Important Breeds (New York: Doubleday: 1905, 1906)

A number of references to Newfoundlands occur prior to the chapter devoted to the breed, with many taken from previously published works. Watson mentions, in his chapter on the "Early History of the Dog," Capt. William Parry's brief reference, in his 1824 Journal of a Second Voyage for the Discovery of a Northwest Passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific, of a Newf nearly attacked by a pack of wolves; there are a couple of mentions of Newf crosses, also from prior sources; he also offers, in the chapter on retrievers and the one on "The Chesapeake Bay Dog," the speculation that shipwrecked Newfoundlands in the Chesapeake Bay were behind the creation of the Chesapeake Bay retriever (321; 325ff).

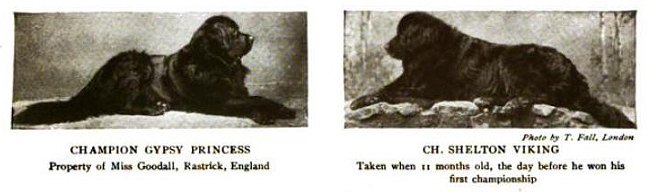

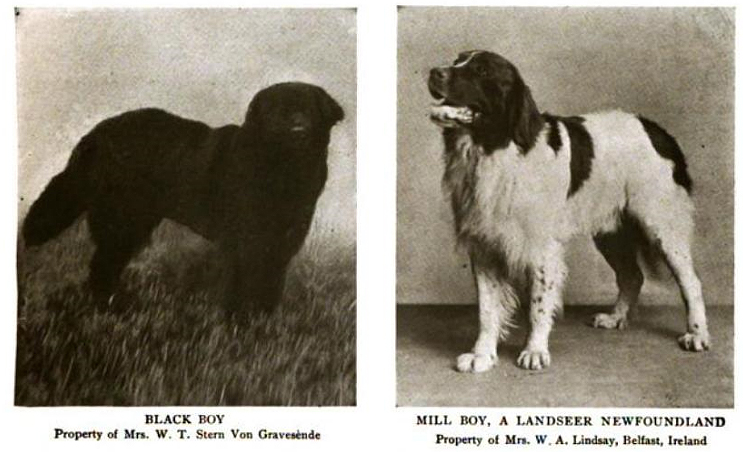

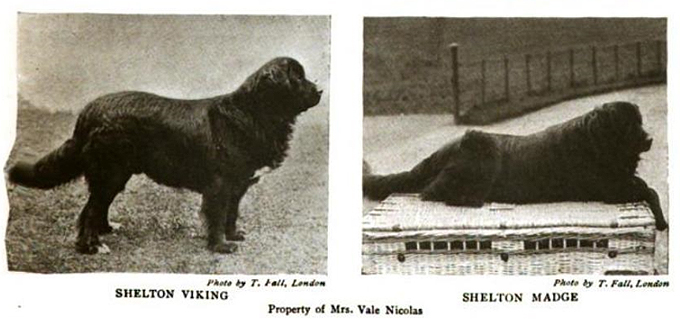

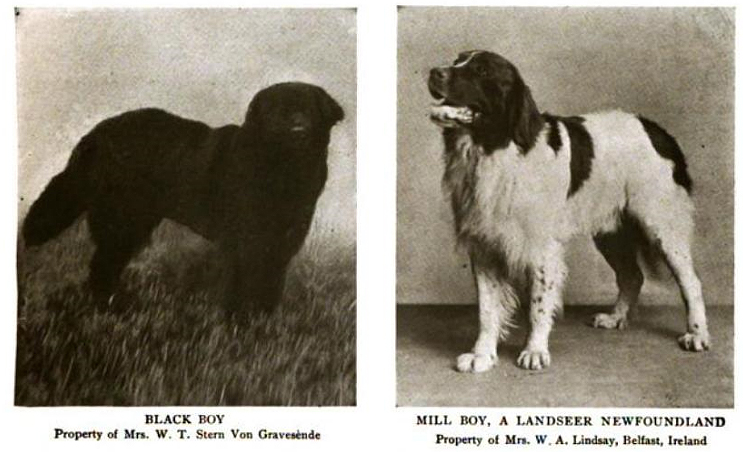

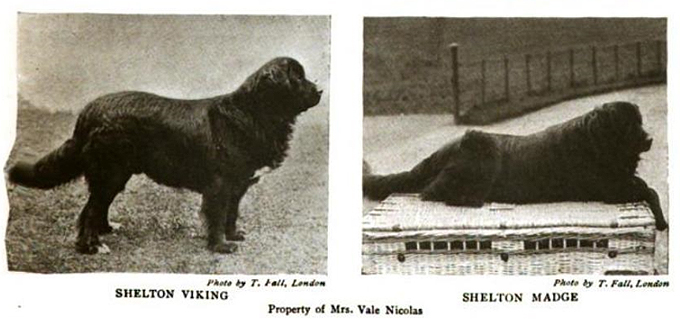

"The Newfoundland Dog" is Chapter 42 in this work (pp. 589 - 591); the text of the chapter is preceded by the following images:

The dog who is shown in two of the above photos, Ch. Shelton Viking, was a highly regarded dog of the time; photos of him also appeared in the 1909 C. S. R. Blue Book of Dogdom; and in the July, 1915, issue of The Dog Fancier as an illustration of the breed standard.

Other illustrations of Newfoundlands in this book included those by Philip Reinangle, Thomas Bewick, Sir Edwin Landseer ("Distinguished Member..."), and A. Cooper, which may be found in the "Fine Arts" section of this website.

Popular belief would no doubt lead to the opinion that the Newfoundland dog would have a very straight history, but such is not the case by any means. In the first place, the early illustrations by Bewick and Reinagle show a long, flat-headed white and black dog. Captain Brown in 1829 gives us a similar dog but seemingly solid black, but he does not specify any colour. Lieutenant-Colonel Hamilton who had visited Newfoundland stands alone in describing the true Newfoundland as a black-and-tan dog. This he calls the true old type and characterises all others as cross-bred dogs. When he was in Newfoundland we cannot state, but he was an experienced investigator and possessed an extensive knowledge of dogs in all parts of the world, so that his conclusions and assertions are entitled to great consideration, even if he stands alone on the black-and-tan statement. The "Naturalist's Library" for which he wrote on dogs was published in 1840, hence we may say he wrote of the breed of 1830. Between that time and 1860 the tan markings appear to have been bred out entirely, and there is little doubt that pure black, rusty black occasionally, became the prevailing colour.

We must recognise that we are not now speaking of a country where dogs were bred for points but a very undeveloped territory, where the dogs were obliged to earn their own living, bred as they liked, and were grievously neglected according to all accounts. Where they originated is not hard to state, for they must have descended from ship dogs. In the old days, which in this breed can be put at 1800 to 1850, there were three varieties, smooth or short-coated, shaggy and curly. The shaggy were the most attractive, and became the popular dog. Up to 1870 the height of dogs on Newfoundland Island ran to 26 inches, anything larger being an exception; and the dog presented to the Prince of Wales when he visited this continent was a monstrosity, a perfect giant, and not considered by any means typical of the breed. It was stated to have measured "considerably over 30 inches." No such dog had ever been known on the island before, hence it was not typical of the breed at home. That they grew much larger when taken as puppies to England, or bred there, is very well known. If the breed had never been taken to England we should have no such dog as is now called the Newfoundland, which is purely an English development from a very common-sized black dog.

In this country we have had one high-class dog — that was Mayor of Bingley, brought over by Mr. Mason in 1881. Since that time we have had two very nice ones in Captain and Black Boy, and about two more that were passably good. All the rest that have been shown as Newfoundlands were plain black dogs, mainly curly.

The Landseer Newfoundland, as the white and black variety is called, got its name from the fact that Sir Edwin Landseer took a fancy to a dog of that colour, and painted it with the title of "A Distinguished Member of the Royal Humane Society." All large water dogs had been called Newfoundlands in England for many years, and Landseer was merely painting what to him was an attractive dog, but not distinguished for great amount of what we now would call type of the breed, any more than is seen in any other large dog that has a rough and shaggy coat. The peculiarity that to our mind is distinctly Newfoundland is the skull development — a sort of water-on the-brain shape, as Dalziel once said to us in speaking of the Clumber. This shape of head is seen in no other large dog, and is only met with in a degree in the Clumber. Another dog that has somewhat of the same head is the Thibet dog, but we cannot suppose that dog had any connection with Newfoundland, and the Thibet dog's head is not so much domed or rounded.

In view of there being such a paucity of the breed in this country, we leave the illustrations to speak for themselves. In the matter of standard we are at a loss to know what to use. That of the Newfoundland Club of England is acknowledged to be quite out of date, but no one cares about amending it. Certainly it is no guide, and its publication would only be misleading. This also applies to the Stonehenge standard of 1870, which also did duty in Dalziel's book.

Compared with most large dogs the Newfoundland is somewhat loosely built, and should be a free, supple mover. Size is desirable, but not to the extent that it overtops character in head, or colour with straightness and quality of coat. A Newfoundland is not primarily a large dog, but size is wanted if you have the other named essentials. He certainly should not gain height by mere length of legs, but get it as the mastiff does by depth of body and legs of suitable length to look neither low nor high on the leg. The legs should be stout of bone and straight, with feet somewhat large, as befits a water dog and not an animal which has to travel on hard roads or at speed. The coat has a decidedly open appearance compared with most water dogs, and has not much undercoat. Glossy black is decidedly preferable to the rusty black one occasionally sees, the consensus of testimony from those competent to give evidence being to the effect that the parti-coloured dog is not a true Newfoundland, so far as being an island dog. Still, as the Newfoundland of England is altogether different from the old type, there is no good reason why variety in colour also should not be permitted. (589 - 591)