[ Kane / Arctic Explorations: The Second Grinnell Expedition in Search of Sir John Franklin, 1853, '54, '55 ]

This book was first published in 1856 by Childs and Peterson, Philadelphia, from which the text and images below are taken.

This expedition, Kane's second in search of the lost Franklin expedition, sailed in May of 1853; after losing his ship to ice and enduring a brutal cross-country journey, Kane returned in October of 1855. He died two years later, largely due, it is believed, to the scurvy and other hardships he suffered on this expedition. (For discussion of his first expedition, click here.)

This volume was illustrated, and I have inclued the Newf-related illustrations in the order in which they occur in the book. The credit for the illustrations, on the title page, reads as follows: "Illustrated by Upwards of Three Hundred Engravings, from Sketches by the Author. Steel Plates executed under the superintendence of J. M. Butler, the Wood Engravings by Van Ingren and Snyder."

On this expedition, Kane took ten — count 'em, TEN — Newfoundland dogs to serve as sled-dogs, in addition to "Esquimaux dogs." He expresses concern for his Newfoundlands when one of the other dogs becomes rabid: "Finally she snapped at Petersen, and fell foaming and biting at his feet. He reluctantly pronounced it hydrophobia, and advised me to shoot her. The advice was well-timed: I had hardly cleared the deck before she snapped at Hans, the Esquimaux, and recommenced her walking trot. It was quite an anxious moment to me; for my Newfoundlanders were around the housing, and the hatch was open. We shot her, of course." (72 - 73)

Hnext mentions the Newfs in reference to the establishment of supply depots on what the men hoped would be their return route, a standard practice for Arctic expeditions in the 19th century.

My plans of future search were directly dependent upon the success of these operations of the fall. With a chain of provision-depots along the coast of Greenland, I could readily extend my travel by dogs. These noble animals formed the basis of my future plans: the only drawback to their efficiency as a means of travel was their inability to carry the heavy loads of provender essential for their support. A badly-fed or heavily-loaded dog is useless for a long journey; but with relays of provisions I could start empty, and fill up at our final station.

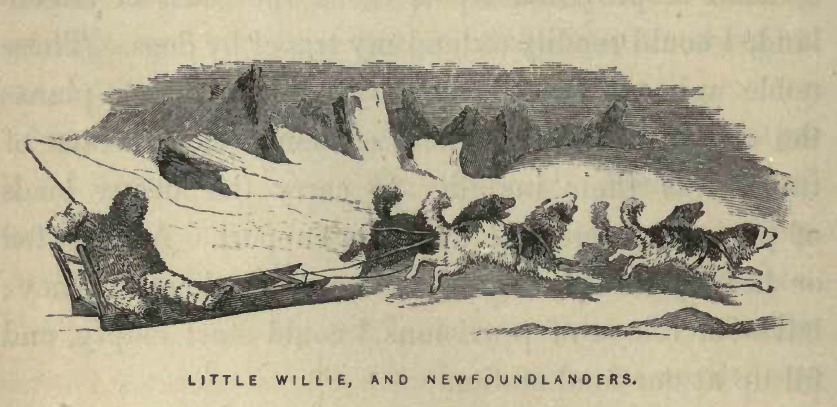

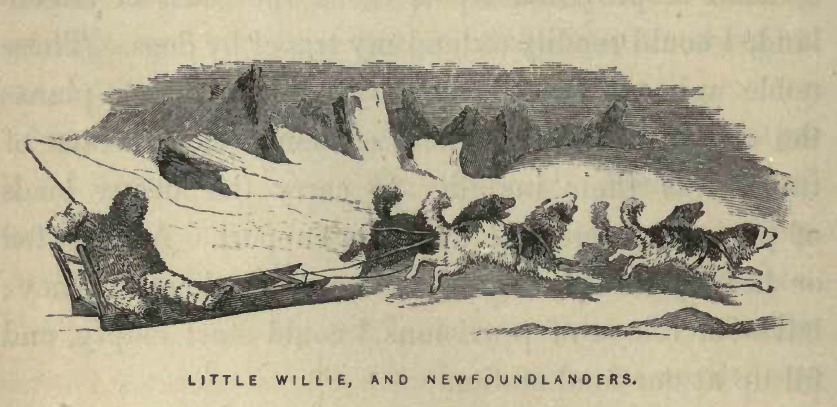

My dogs were both Esquimaux and Newfoundlanders. Of these last I had ten: they were to be carefully broken, to travel by voice without the whip, and were expected to be very useful for heavy draught, as their tractability would allow the driver to regulate their pace. I was already training them in a light sledge, to drive, unlike the Esquimaux, two abreast, with a regular harness, a breast-collar of flat leather, and a pair of traces. Six of them made a powerful travelling-team; and four could carry me and my instruments, for short journeys around the brig, with great ease. (109)

The first Newf-related image occurs in the middle of page 110:

"Little Willie" is the name Kane and his crew gave to the sledge pictured here

On page 111 Kane continues the discussion of his provisioning strategy:

I determined to hold back my more distant provision parties as long as the continued daylight would permit; making the Newfoundland dogs establish the depots within sixty miles of the brig.

Kane recounts a rather harrowing near-escape on the ice when he was travelling, with four Newfoundland sled dogs, in search of an overdue provisioning party:

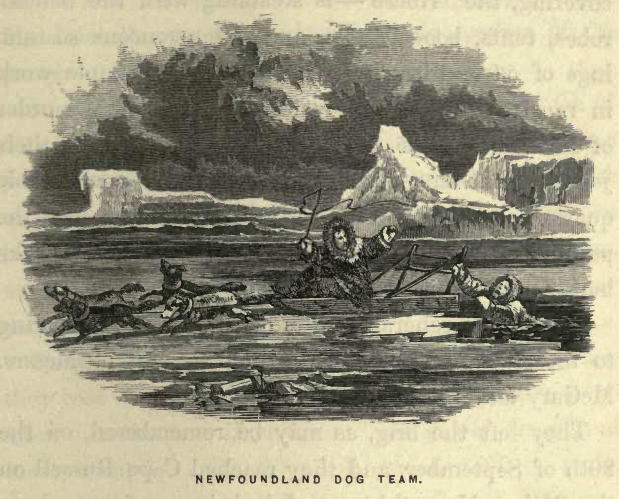

"October 10, Monday. — Our depot party has been out twenty days, and it is time they were back: their provisions must have run very low, for I enjoined them to leave every pound at the depSt they could spare. I am going out with supplies to look after them. I take four of our best Newfoundlanders, now well broken, in our lightest sledge; and Blake will accompany me with his skates. We have not hands enough to equip a sledge party, and the ice is too unsound for us to attempt to ride with a large team. The thermometer is still four degrees above zero." (126)

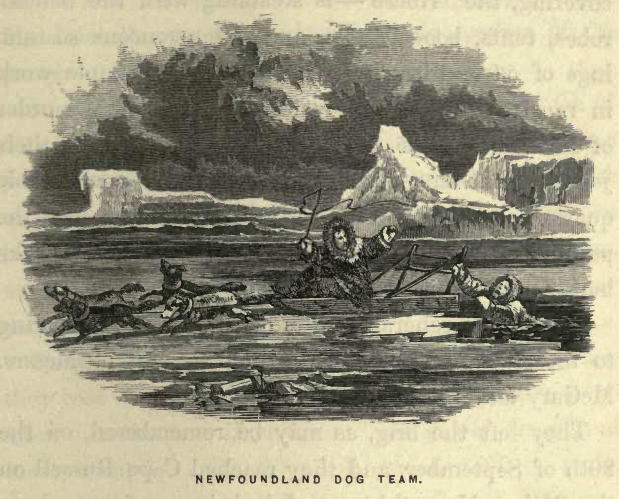

I Found little or no trouble in crossing the ice until we passed beyond the northeast headland, which I have named Cape William Wood. But, on emerging into the channel, we found that the spring tides had broken up the great area around us, and that the passage of the sledge was interrupted by fissures, which were beginning to break in every direction through the young ice.

My first effort was of course to reach the land; but it was unfortunately low tide, and the ice-belt rose up before me like a wall. The pack was becoming more and more unsafe, and I was extremely anxious to gain an asylum on shore; for, though it was easy to find a temporary refuge by retreating to the old floes which studded the more recent ice, I knew that in doing so we should risk being carried down by the drift.

The dogs began to flag; but we had to press them: — we were only two men; and, in the event of the animals failing to leap any of the rapidly-multiplying fissures, we could hardly expect to extricate our laden sledge. Three times in less than three hours my shaft or hinder dogs went in; and John and myself, who had been trotting alongside the sledge for sixteen miles, were nearly as tired as they were. This sta.te of things could not last; and I therefore made for the old ice to seaward.

We were nearing it rapidly, when the dogs failed in leaping a chasm that was somewhat wider than the others, and the whole concern came down in the water. I cut the lines instantly, and, with the aid of my companion, hauled the poor animals out. We owed the preservation of the sledge to their admirable docility and perseverance. The tin cooking-apparatus and the air confined in the India-rubber coverings kept it afloat till we could succeed in fastening a couple of seal-skin cords to the cross-pieces at the front and back. By these John and myself were able to give it an uncertain support from the two edges of the opening, till the dogs, after many fruitless struggles, carried it forward at last upon the ice.

Although the thermometer was below zero, and in our wet state we ran a considerable risk of freezing, the urgency of our position left no room for thoughts of cold. We started at a run, men and dogs, for the solid ice; and by the time we had gained it we were steaming in the cold atmosphere like a couple of Nootka Sound vapor-baths.

We rested on the floe. We could not raise our tent, for it had frozen as hard as a shingle. But our buffalorobe bags gave us protection; and, though we were too wet inside to be absolutely comfortable, we managed to get something like sleep before it was light enough for us to move on again.

The journey was continued in the same way; but we found to our great gratification that the cracks closed with the change of the tide, and at high-water we succeeded in gaining the ice-belt under the cliffs.

This belt had changed very much since my journey in September. The tides and frosts together had coated it with ice as smooth as satin, and this glossy covering made it an excellent road. The cliffs discharged fewer fragments in our path, and the rocks of our last journey's experience were now fringed with icicles. I saw with great pleasure that this ice-belt would serve as a highway for our future operations.

The nights which followed were not so bad as one would suppose from the saturated condition of our equipment. Evaporation is not so inappreciable in this Arctic region as some theorists imagine. By alternately exposing the tent and furs to the air, and beating the ice out of them, we dried them enough to permit sleep. The dogs slept in the tent with us, giving it warmth as well as fragrance. What perfumes of nature are lost at home upon our ungrateful senses! How we relished the companionship!

Kane recounts another incident involving a return from an exploring trip and a nearly disastrous accident:

On this return I had much less difficulty with the ice-cracks; my team of Newfoundlanders leaping them in almost every instance, and the impulse of our sledge carrying it across. On one occasion, while we were making these flying leaps, poor Bonsall was tossed out, and came very near being carried under by the rapid tide. He fortunately caught the runner of the sledge as he fell, and I succeeded, by whipping up the dogs, in hauling him out. He was, of course, wet to the skin; but we were only twenty miles from the brig, and he sustained no serious injury from his immersion. (132 - 133)

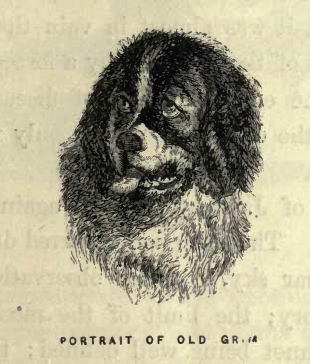

Kane's log entry for Thurday, Dec. 22 (1853) suggests the depth of feeling he had for his Newfoundland dogs, two of whom are identified by name here ("Cerberus," named after the three-headed dog that guards the entrance to the underworld in Greek mythology, and "Old Grim"):

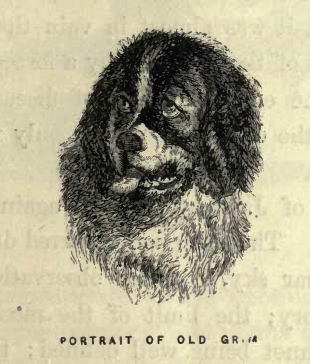

There is an excitement in our little community that dispenses with reflections upon the solstitial night. 'Old Grim' is missing, and has been for more than a day. Since the lamented demise of Cerberus, my leading Newfoundlander, he has been patriarch of our scanty kennel.

"Old Grim was 'a character' such as peradventure may at some time be found among beings of a higher order and under a more temperate sky. A profound hypocrite and time-server, he so wriggled his adulatory tail as to secure every one's good graces and nobody's respect. All the spare morsels, the cast-off delicacies of the mess, passed through the winnowing jaws of 'Old Grim,' — an illustration not so much of his eclecticism as his universality of taste. He was never known to refuse any thing offered or approachable, and never known to be satisfied, however prolonged and abundant the bounty or the spoil.

"Grim was an ancient dog: his teeth indicated many winters, and his limbs, once splendid tractors for the sledge, were now covered with warts and ringbones. Somehow or other, when the dogs were harnessing for a journey, 'Old Grim' was sure not to be found; and upon one occasion, when he was detected hiding away in a cast-off barrel, he incontinently became lame. Strange to say, he has been lame ever since except when the team is away without him.

"Cold disagrees with Grim; but by a system of patient watchings at the door of our deck-house, accompanied by a discriminating use of his tail, he became at last the one privileged intruder. My seal-skin coat has been his favorite bed for weeks together. Whatever love for an individual Grim expressed by his tail, he could never be induced to follow him on the ice after the cold darkness of the winter set in; yet the dear good old sinner would wriggle after you to the very threshold of the gangway, and bid you good-bye with a deprecatory wag of the tail which disarmed resentment.

His appearance was quite characteristic: — his muzzle roofed like the old-fashioned gable of a Dutch garret-window; his forehead indicating the most meagre capacity of brains that could consist with his sanity as a dog; his eyes small; his mouth curtained by long black dewlaps; and his hide a mangy russet studded with chestnut-burrs: if he has gone indeed, we 'ne'er shall look upon his like again.' So much for old Grim!

"When yesterday's party started to take soundings, I thought the exercise would benefit Grim, whose timeserving sojourn on our warm deck had begun to render him over-corpulent. A rope was fastened round him; for at such critical periods he was obstinate and even ferocious; and, thus fastened to the sledge, he commenced his reluctant journey. Reaching a stopping-place after a while, he jerked upon his line, parted it a foot or two from its knot, and, dragging the remnant behind him, started off through the darkness in the direction of our brig. He has not been seen since. Parties are out with lanterns seeking him ; for it is feared that his long cord may have caught upon some of the rude pinnacles of ice which stud our floe, and thus made him a helpless prisoner. The thermometer is at 44°.6 below zero, and old Grim's teeth could not gnaw away the cord.

"December 23, Friday. – Our anxieties for old Grim might have interfered with almost any thing else; but they could not arrest our celebration of yesterday. Dr. Hayes made us a well-studied oration, and Morton a capital punch; add to these a dinner of marled beef, – we have two pieces left, for the sun's return and the Fourth of July, — and a bumper of champagne all round; and the elements of our frolic are all registered." We tracked old Grim to-day through the snow to within six hundred yards of the brig, and thence to that mass of snow-packed sterility which we call the shore. His not rejoining the ship is a mystery quite in keeping with his character." (148 - 151)

"Old Grim" is never mentioned again by Kane.

Later in the book Kane is detailing the hardships his men experienced in dealing with the cold and never-ending darkness of an Arctic winter; he carefully records the temperatures — the chilliest being 67 degrees below 0 — and how the cold affected the supplies and the crew. Remarking upon the depressant effect of the cold, Kane writes that even the dogs seemed affected:

"The influence of this long, intense darkness was most depressing. Even our dogs, although the greater part of them were natives of the Arctic circle, were unable to withstand it. Most of them died from an anomalous form of disease, to which, I am satisfied, the absence of light contributed as much as the extreme cold. I give a little extract from my journal of January 20th.

"This morning at five o'clock — for I am so afflicted with the insomnium of this eternal night, that I rise at any time between midnight and noon — I went upon deck. It was absolutely dark; the cold not permitting a swinging lamp. There was not a glimmer came to me through the ice-crusted window-panes of the cabin. While I was feeling my way, half puzzled as to the best method of steering clear of whatever might be before me, two of my Newfoundland dogs put their cold noses against my hand, and instantly commenced the most exuberant antics of satisfaction. It then occurred to me how very dreary and forlorn must these poor animals be, at atmospheres of +10° in-doors and –50° without, – living in darkness, howling at an accidental light, as if it reminded them of the moon, — and with nothing, either of instinct or sensation, to tell them of the passing hours, or to explain the long-lost daylight. They shall see the lanterns more frequently."

I may recur to the influence which our long winter night exerted on the health of these much-valued animals. The subject has some interesting bearings; but I content myself for the present with transcribing another passage from my journal of a few days later.

"January 25, Wednesday. – The mouse-colored dogs, the leaders of my Newfoundland team, have for the past fortnight been nursed like babies. No one can tell how anxiously I watch them. They are kept below, tended, fed, cleansed, caressed, and doctored, to the infinite discomfort of all hands. To-day I give up the last hope of saving them. Their disease is as clearly mental as in the case of any human being. The more material functions of the poor brutes go on without interruption: they eat voraciously, retain their strength, and sleep well. But all the indications beyond this go to prove that the original epilepsy, which was the first manifestation of brain disease among them, has been followed by a true lunacy. They bark frenziedly at nothing, and walk in straight and curved lines with anxious and unwearying perseverance.

"They fawn on you, but without seeming to appreciate the notice you give them in return; pushing their heads against your person, or oscillating with a strange pantomime of fear. Their most intelligent actions seem automatic: sometimes they claw you, as if trying to burrow into your seal-skins; sometimes they remain for hours in moody silence, and then start off howling as if pursued, and run up and down for hours. "

So it was with poor Flora, our 'wise dog.' She was seized with the endemic spasms, and, after a few wild violent paroxysms, lapsed into a lethargic condition, eating voraciously, but gaining no strength. This passing off, the same crazy wildness took possession of her, and she died of brain disease (arachnoidal effusion) in about six weeks. Generally, they perish with symptoms resembling locked-jaw in less than thirty-six hours after the first attack." (156 -157)

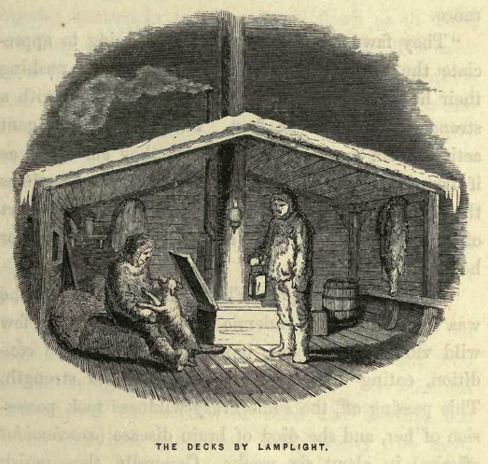

"The Decks by Lamplight"

The impact of the loss of most of the dogs is duly noted by Kane:

But I felt that our work was unfinished. The great object of the expedition challenged us to a more northward exploration. My dogs, that I had counted on so largely, the nine splendid Newfoundlanders and thirty-five Esquimaux of six months before, had perished; there were only six survivors of the whole pack, and one of these was unfit for draught. Still, they formed my principal reliance, and I busied myself from the very beginning of the month in training them to run together. (163)

There are no additional references to Newfoundlands in this book.