[ Reynolds / The Caravan ]

This play, the full title of which is The Caravan; or, The Driver and His Dog, was written by the prolific English playwright Frederic Reynolds (1764 - 1841), the author of a number of popular plays, most of which were considered low- to middle-brow entertainment. (Reynolds, for what it's worth, is largely unknown now, even among academic specialists in this period of British literature.)

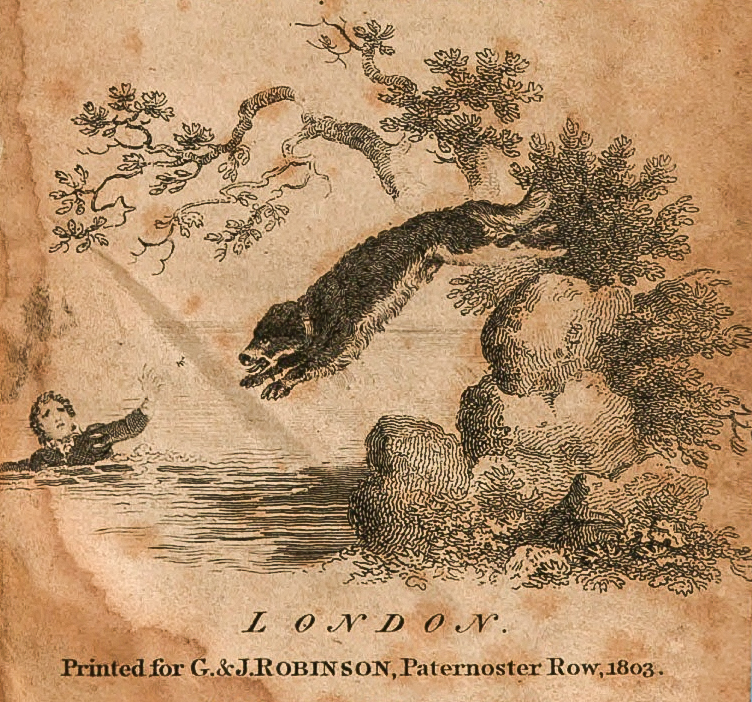

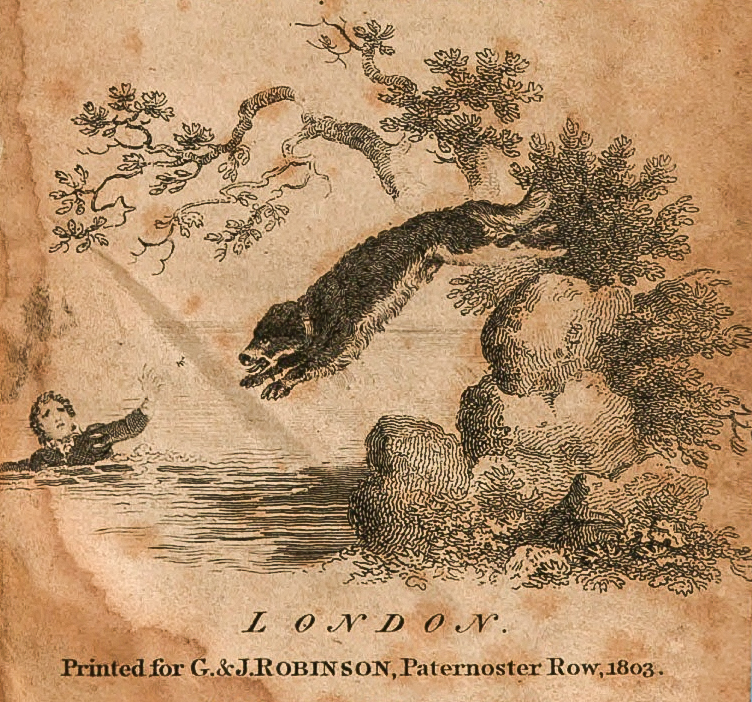

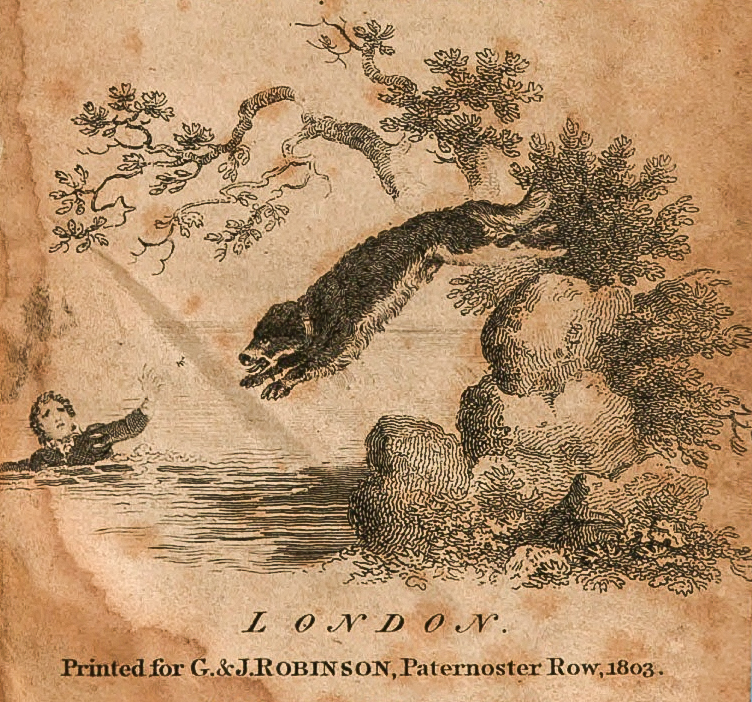

The Caravan, which debuted in late 1803, was one of his more successful works, due in large part to the presence of two innovations: (1) the use of flowing water on stage; and (2) the presence of a Newfoundland dog as one of the significant characters in the play. This play was not only popular, proving a significant commercial success — it ran for an-almost-unheard-of 40 consecutive nights — but it also became a bit infamous.

At the time, many literary and cultural critics were troubled by the proliferation and popularity of lowbrow drama, and the quick notoriety of The Caravan, with its use of a Newfoundland jumping into a pool of water onstage to rescue a "drowning" child, made the play something of a lightning rod for critics. I discuss this in more detail elsewhere here at The Cultured Newf: see The Cultured Newf's page on an article in Walker's Hibernian Magazine for a discussion centering on a review of The Caravan; you can also follow this link to a full treatment of how this play and its Newfoundland became prominent components of cultural debate in the first decade of the 19th Century in Britain. (This play also inspired hundreds of imitation "dog dramas" that were performed for decades afterward; see, for example, this review in The Times (London), in 1826, of a Newfoundland's highly regarded performance in a stage adaptation of Robinson Crusoe.)

"Carlo," the name of the Newfoundland in Reynolds' play, quickly becomes a recognizable reference in early- to mid-19th Century British culture. By way of example: a ballad from 1843 celebrates the life-saving abilities of Newfoundlands by dramatizing the rescue of a drowning sailor by a Newf named Carlo.

The popularity of this play even prompted the English writer Eliza Fenwick (up to this point mostly associated with radical political figures) to write a children's book, first published in 1804 and reprinted several times, entitled The Life of the Famous Dog Carlo.

This play constitutes the earliest reference I have yet found to the use of Newfoundlands in any sort of theatrical or dramatic production.

Cover image for the 3rd edition (1803) of The Caravan, printed in London for G. & J. Robinson

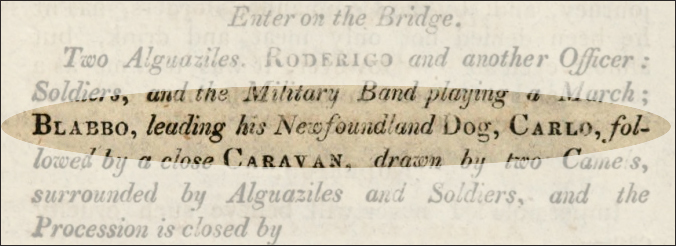

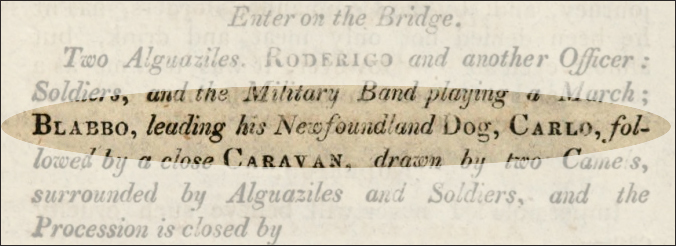

An early stage direction in this play explicity identifies the dog as a Newfoundland:

Enter on the Bridge. . . . Blabbo, leading his Newfoundland Dog, Carlo. . . . (Act I, scene i)

(Yes, one of the characters — the caravan driver — is actually named "Blabbo." Although this play is billed as a "serio-comic romance," there's really not much that's "serio" about it.)

The plot of the play is, like most dramas of the period, rather melodramatic and a bit over-the-top, and the work, which is brief, fast-paced, and utterly lacking in character development or psychological subtlety, never seems to take itself all that seriously. The basic premise is that an important prisoner, a marquis who is said for some unspecified reason to be a traitor, is being sent from Barcelona to Madrid largely so he could be starved to death en route. But the caravan driver, Blabbo, gave the prisoner food intended for himself and his dog Carlo, allowing the prisoner to survive.

In Madrid the marquis is thrown into jail but soon escapes, yet before he can flee to Africa he is recaptured. He is then placed on board a ship that is to be blown up, thus ensuring his destruction. Meanwhile the prisoner's wife, the marchioness, refuses the amorous advances of the Spanish Regent, upon which refusal she hears the ship carrying her husband blown up and her child is thrown into the sea. Carlo the Newf rescues the child, and since it turns out the marquis had fled the ship before it blew up, everything ends happily ever after for all the good characters.

Most of the references to the dog (and there are only a handful) are vague and of little consequence to the story, though we do learn Blabbo is very attached to his dog when he thanks the man who released him from prison by saying

"I will make some return: ask me for any thing except my Dog: ask for my purse, my — I’ll tell

you what — there’s a charming girl at Madrid — one Rosa de Villarea. — I’ll give you her." (Act II, scene i).

Blabbo further explains his release to his paramour Rosa by remarking that when his jailer, Pedro, had left the prison to purchase provisions...

Carlo accidentally follow’d him. — from what motive I know not, but it was a lucky one for me and Pedro — for he, on

his return, being attack’d by two of Arabbo's banditti, the Dog lamed one and throttled the other, and in return, my freedom was secured.

Rosa. Oh — pray indulge yourself, Sir — I neither trouble my head about four or two legged animals.

Blabbo. Don’t you? — then, to the four legged animal I’m sure you are ungrateful — For once, when you were bathing — didn’t he kindly take it into his head you were drowning, and pull you out among a hundred admiring spectators? and another time, when he was blam’d and beat for breaking one of the Marquis’s fine looking-glasses, did he ever tell that it was the work of our romping and kissing, Rosa?

The dog next appears in the climactic scene of the play. The Marchioness has refused the Regent's seduction so her son, Julio, is taken from her by one of the play's villains, Ferndinand, causing the Marchioness to faint. The boy is then hurled into the sea:

Ferdinand appears on the Rock, with Julio in his arms, followed by Blabbo, and his Dog Carlo; Ferdinand throws the Child into the Sea. — The noise of his falling into the water recovers the Marchioness, who Starts up, and Screams — at the same instant — the Dog Carlo leaps from the Rock into the Water and is seen swimming after the Child.

Blabboo, (on the Rock.)

Don’t be afraid; Carlo never fail’d in his life! Now he gets near him! push on, boy! push on! now he's nearer — now! huzza! he has him! he has him! the child's safe — the mother's happy! and now, master Ferdinand, I’ll try and give you a ducking.

The play then wraps up very quickly: word arrives that the evil Regent has been deposed and the rightful (and virtuous) King has claimed the throne; the Marquis, having escaped from the ship before its destruction, has been granted his freedom. All the "good" characters gather on stage, their entry announced by Rosa, the object of Blabbo's affection.

Rosa. . . . . And see here he [the Marquis] comes, alive and merry, with his dear friend, and faithful Carlo.

(Flourish. March.)

Enter Roderigo, Marquis, Carlo, Soldiers, etc.

Enter Blabbo.

Blabbo. Damme! I’ve sous’d him but where are they? where’s the young Marquis, and his dear preserver? (gets between Julio and Carlo.) Oh! bless you both! and bless heaven for making me master of this dear treasure! (kissing Carlo.) Ay; and of this (jumping up and kissing Rosa.) For, henceforward, Rosa, you must love, honour, and obey the "Driver," and I hope no body will give either him or his dog an ill name.

One contemporary review of The Caravan remarks that there were actually two dogs used in this play, one a mastiff made up to look like a Newf (this dog was said to belong to the actor who played Blabbo, the dog's owner in the play), and a Newfoundland which was used to jump into the water and rescue the child but which could not bear the heat of the theater.

A sad side note regarding the fate of the Newfoundland in The Caravan comes from an unlikely source, a work entitled The Epicure's Almanack, or Calendar of Good Living, essentially a guide to food and drink in the London metropolitan area. The guide for 1815 (published in London by Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown) has this side comment about the dog who performed the onstage rescue in Reynold's play, which comes in a discussion of two of the best "a la mode beef houses in London:"

. . . The Old Thirteen Cantons and the New Thirteen Cantons, both regularly licensed as public-houses. The former is kept by Mr. Thomas, and the latter by Mr. Johnson. . . . Mr. Johnson was the master of the famous dog Carlo, who once enacted so capital a part on the boards of Old Drury. The sagacity of this animal was so famous,

that it brought as many customers to Mr. Johnson as did the excellence of his fare. At length, unhappily, a report was spread that the faithful animal had been bitten by a mad dog, and Mr. Johnson was reluctantly compelled to sign his death-warrant. (174 - 175)

Read a contemporary review of the play in Walker's Hibernian Magazine here at The Cultured Newf; there's also a positive review in Sporting Magazine.

Here's the full text of The Caravan at The Hathi Trust Digital Library.