[ Smith / Everymanís Book of the Dog ]

The text below is taken from A(rthur) Croxton Smith, Everymanís Book of the Dog (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1910).

This general introduction to dogs makes several references to Newfoundlands.

The first comes in a "which breed is best for you?" discussion:

When you have once made up your mind to keep a dog you are only at the beginning of your troubles. . . . The difficulty is to know which variety shall have the benefit of your patronage. Is it to be large or small? A Toy Terrier or a lordly St. Bernard? The chances are that you fix upon one of the larger kinds: they look so much more imposing, they would impress your friends, and, of course, they would be splendid guards. You settle on a Great Dane or a Newfoundland, and are perfectly content. A night's reflection, however, brings about a modification of your views. (10)

. . . .

By, the end of the day it is quite apparent that a Collie or Retriever, is more suitable for you in every way. You have wanted one all along, and it was a mistake, this philandering with the idea of a Newfoundland or Dane. (11)

The next mention occurs at the beginning of Chapter 21, "The Retriever":

For general all-round purposes, the Retriever is one of the most popular dogs in country places. Only forty years ago, when he first began to have a vogue, he was little else than a small Newfoundland, and it took some time to reduce the breed to workable dimensions. (p. 108)

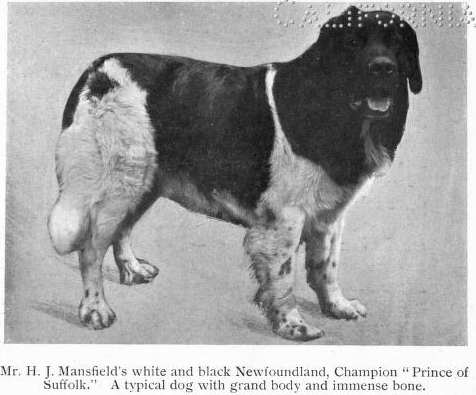

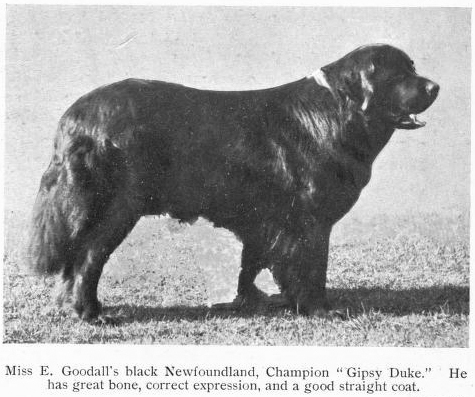

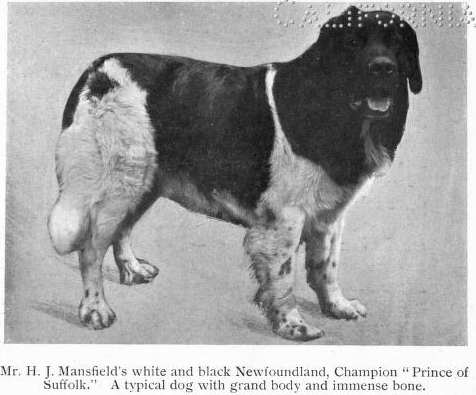

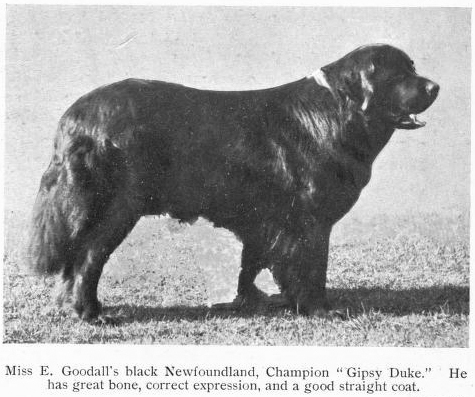

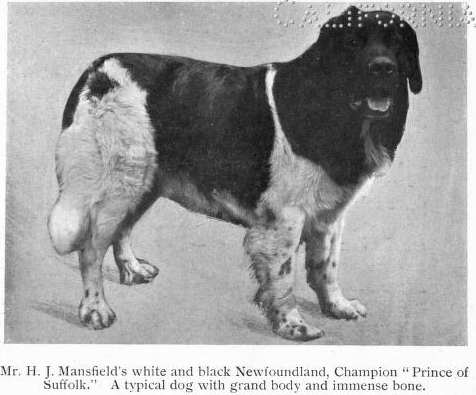

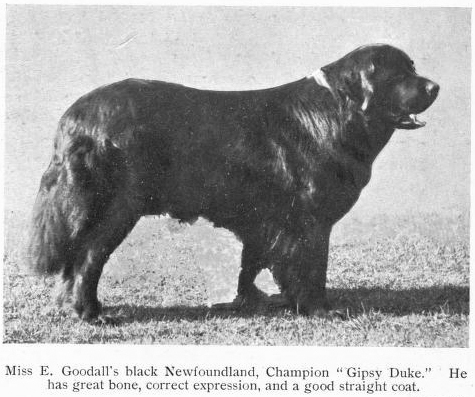

Chapter 40 is devoted to the Newfoundland, and is preceded by the two images reproduced below:

(The dog pictured immediately above, Ch. Gipsy Duke, is also featured in a Newfoundland breed column, with photo, in the July, 1915, issue of Dog Fancier magazine.)

It is curious how early associations cling to one through life. Most of us in childhood saw Landseer's well-known picture, "A Distinguished Member of the Royal Humane Society," and from that period on we regarded the Newfoundland primarily as a saviour of human life. This character is well deserved, for many are the authentic stories of people rescued from sea or river by his agency. The form of the dog is peculiarly adapted to enable him to perform the duties expected from him. His powerful body, not too cobby, the rudder-like tail, the comparatively short, heavily-boned legs, with big webbed feet, all mark him out as suited for the water or for moving heavy weights. In his native land he was much used for draught purposes, and so we see in him strongly-marked utility points. He is no "fancy" fellow, although so handsome, and his expression conveys a sense of dignity and intelligence compatible with close and intimate association with mankind. Miss Goodall says of her champion, "Gipsy Duke," whose portrait is reproduced: "He is a nice-tempered dog, very affectionate, a splendid guard and water dog, as are all Newfoundlands. As a breed I prefer them to any other for their companionable qualities and for devotion to master or mistress. They are intensely affectionate."

The white and black dog is frequently called a "Landseer," after the great artist who immortalised him, but there is no further justification for the name. He is more properly classified as White and Black. Much attention is bestowed upon the correct distribution of his markings, which should observe a certain regularity. For instance, the black should appear as a saddle on the back, which may be divided by a white line in the centre, as a crupper near the root of the tail, and on the head and ears, the muzzle being white, as well as a blaze between the eyes. Occasionally we see a bronze-coloured dog, ibut personally I do not think it as pleasing as the markings referred to or the pure black.

The Newfoundland should have no exaggerated points, but exhibit his characteristics in due proportion. Obviously he should not be too heavy, unless we are to depart violently from the original type, as such a dog could not well display the necessary activity. The "short muzzle," too, should be interpreted in a reasonable manner, for if it is abbreviated too much it would not be easy for the dog to seize and hold any object in the water.

No direct evidence tells us when the Newfoundland was first introduced into this country, nor do we know much about his history in his own. It is not by any means certain that he was indigenous to the island after which he is named. There is quite as much reason for supposing that settlers from Europe may have taken with them dogs of somewhat similar appearance from which he has been produced. He is undoubtedly very dissimilar from the native dogs of the cold regions north of the American continent, these having prick ears and being of a wolfish type. To-day the breed is practically extinct in Newfoundland, but we know, that at one time they were employed in drawing carts laden with fuel and other articles, and were consequently much esteemed. Frequently, it is said, they were subjected to ill-usage, badly fed, and much over-worked. Innumerable anecdotes could be cited having a bearing upon the life-saving propensities of these noble animals, but one, recorded by Youatt, must suffice: A vessel was driven ashore near Lydd, amid a furious surf, through which no boat could be launched. At length a gentleman arrived with a Newfoundland. Directing the attention of the dog to the vessel, he gave him a stick to carry and sent him into the sea. He fought his way through the waves, but was unable to approach close to the vessel. The men on board, however, threw him a stick to which a rope was attached, and this he dragged to the shore with the utmost difficulty. By this means communication was set up and every man was rescued.

The Newfoundland Club's description is appended:

SYMMETRY AND GENERAL APPEARANCE. The dog should impress the eye with strength and great activity. He should move freely on his legs, with the body swung loosely between them, so that a slight roll in gait should not be objectionable; but at the same time a weak or hollow back, slackness of the loins, or cow hocks should be a decided fault.

HEAD. Should be broad and massive, flat on the skull, the occipital bone well developed; there should be no decided stop, and the muzzle should be short, clean cut, rather square in shape, and covered with short, fine hair.

COAT. Should be flat and dense, of a coarsish texture and oily nature, and capable of resisting the water. If brushed the wrong way, it should fall back into its place naturally.

BODY. Should be well ribbed up, with a broad back. A neck strong, well set on to the shoulders and back, and strong muscular loins.

FORELEGS. Should be perfectly straight, well covered with muscle, elbows in but well let down, and feathered all down.

HINDQUARTERS AND LEGS. Should be very strong; the legs should have great freedom of action, and a little feather. Slackness of loins and cow hocks are a great defect; dew claws are objectionable and should be removed.

CHEST. Should be deep and fairly broad, and well covered with hair, but not to such an extent as to form a frill.

BONE. Massive throughout, but not to give a heavy, inactive appearance.

FEET. Should be large and well shaped. Splayed or turned-out feet are objectionable.

TAIL. Should be of moderate length, reaching down a little below the hocks it should be of fair thickness and well covered with long hair, but not to form a flag. When the dog is standing still and not excited it should hang downwards, with a slight curve at the end; but when the dog is in motion, it should be carried a trifle up, and when he is excited, straight out, with a slight curve at the end. Tails with a kink in them or curled over the back are very objectionable.

EARS. Should be small, set well back, square with the skull, lie close to the head, and covered with short hair, and no fringe.

EYES. Should be small, of a dark-brown colour, rather deeply set, but not showing any haw, and they should be rather wide apart.

COLOUR. Jet black. A slight tinge of bronze, or a splash of white on chest and toes is not objectionable.

HEIGHT AND WEIGHT. Size and weight are very desirable so long as symmetry is maintained. A fair average height at the shoulders is 27 inches for a dog and 25 inches for a bitch, and a fair iaverage weight is respectively: dogs, 140 lb. to 150lb.; bitches, 110lb. to 120lb.

OTHER THAN BLACK. Should in all respects follow the black except in colour, which may be almost any, so long as it disqualifies for the black class, but the colours most to be encouraged are black and white and bronze. Beauty in markings to be taken greatly into consideration. (183 - 187)

The next Newf reference follows in the very next chapter, on St. Bernards:

It is only fitting that the Newfoundland and St. Bernard should be coupled together, both having been employed in saving life, the one from a watery grave, the other from cold and exposure on a Swiss pass. (188)

Also from the St. Bernard chapter, during a discussion of the introduction of other breed strains into the Saint:

The avalanche which swept away the old breed occurred in 1815, and in another fifteen years the strain was obviously deteriorating on account of consanguinity. The monks therefore sought an outcross, which probably took the form, in the first instance, of a Newfoundland bitch.

There is a final reference to Newfs in Chapter 58, "The Poodle," in which Smith quotes William Youatt's remark (in The Dog [1845]) that Poodles have "all the sagacity of the Newfoundland." (267)