[ Webb / Dogs: Their Points, Whims, Instincts, and Peculiarities ]

I can find no information on Henry Webb, who served as editor of this book; the individual chapters on different breeds had their own authors or contributors.

This book appears to have been first published in 1872 (London: Dean and Son), and reprinted once or twice in the next few years.

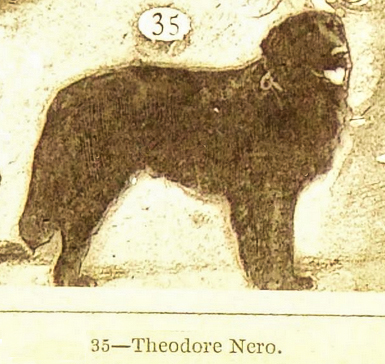

Newfoundlands are mentioned several times in passing, often as genetic contributors to, or in comparison to, other breeds. They are treated at length in their own chapter, which was written by Gordon Stables, Royal Navy physician and prolific writer of both non-fiction and fiction, who is represented by two works discussed here at The Cultured Newf: Ladies' Dogs as Companions (1879), and Our Friend the Dog. Stables is credited — most enthusiastically by himself — as the first person to refer to white-and-black Newfoundlands as "Landseer" Newfoundlands. He begins the Newfoundland chapter with an anecdote about one of his own Newfoundlands, Theodore Nero, whom he discusses in both of his works just mentioned.

The following interesting and amusing article on the noble breed of Newfoundlands contributed by Dr. Stables of H.M.S. Pembroke we give in extenso.

"God bless me, Jack," said I, "who would have dreamt of seeing you here?"

"Do you question my right?" answered Jack, smiling, as he held out his brown hand to return my greeting. Jack was first mate of an American vessel hailing from the northern coasts of that country. We had been together at college in the far north, but Jack's unusual facetiousness, love of fun, and abnormal sense of the ridiculous, had gained for him, instead of a degree, rustication. I had been sitting in the snuggery of an hotel in one of the fair cities of the sister isle, famed more for its poteen than its patriotism, enjoying what an Irishman called his three pays (pís), — the pipe, the pot, and the paper, — when my friend entered in his usual slap-dash style. I was really glad to see him, and it was some time before we could think of aught but ourselves. After the first rattling fire of questions and answers had in some measure subsided, says Jack to me —

"Well, I've brought him old fellow, and won't he be a beauty!"

"Brought him," said I; "brought whom?"

"Why, man, your dog; wasn't it your last words to me before I sailed?"

"By George," cried I, "have you? Where is he?"

"Here," said Jack, and turning towards the door with melodramatic action. "Theodore Nero, jump!" he cried. There was a loud impatient bark outside, then a bound against the top of the door, which opened with a dash, and the present brown-eyed subject of these memoirs stood before me for the first time, looking anxiously up into Jack's face as if for further orders. It was fully a minute before either of us spoke or the dog moved, by which time I was convinced Jack had made me a noble present.

Jack marked with pleasure my beaming face, then shook my hand. "He's yours," he said; "develop him, as I know you can. He's but a puppy of seven months; but when he grows" —

"Grows!" interrupted I, pointing to the marks of his paws on the door, like the imprint of a pair of ? muddy boxing gloves, at least five and a half feet from the ground.

Nero submitted to my caresses with very bad grace, for a divided heart is no part of a real Newfoundland's nature; and he never shows a spark of affection where he does not feel it. Smaller dogs on the other hand often pretend friendship — this is mere policy, and generally instigated by fear. Observe a little wiry terrier or street-bred cur come suddenly on a large Newfoundland on the street; observe with what abject servility of motion and action he crawls up to him, his belly in the dust, and his waggling tail between his legs, while with raised eyes he seems to say, "Oh what a noble dog you are! What arms! what legs! and what a head! and how I love you all at once; but you wouldn't eat a poor little cur like me, would you?"

But the Newfoundland, strong in the sense of his own might, despises subterfuge, and never stoops to falsehood.

Thinking the nearest road to Nero's confidence was through his stomach, I ordered a plate of chicken bones, and a large hunk of bread for him. This I gave him with my own hand and he seemed to think he had completely repaid me with a wag of his monstrous tail; a tail by-the-bye which would do excellently well as a punka, and with which he is constantly making raids on the crockery and sweeping glasses and tumblers from the table.

On my friend's departure, having procured a cord, which I was quietly allowed to place about Nero's neck, we made our exit, and commenced our journey to my lodgings; the dog taking charge, and dragging his newly made master after him at a most undignified trot. I was too well pleased, however, at his taking the right road, to grumble. My pleasure was short-lived. On coming to the end of the street, after a glance or two up and down, he commenced to drag again, and, as the aeronauts say, we now "took a westerly direction" — my road being to the east. This, of course I opposed. Hitherto, it would seem he had ignored my presence, evidently considering me as so much dead weight which, somehow, had got attached to him; he now turned round and deliberately surveyed me in a manner which made me feel anything but comfortable. By exerting all my strength and powers of persuasion, I just succeeded so far: Master Nero sat down, but "Home with me? No; he could not think of such a thing."

As a crowd soon collected, and as several little boys unhesitatingly put me down as a professional dog-stealer, I had to try to look as unconcerned as possible, though feeling very ill at ease, while never Nero sat on his haunches, with his red tongue over lapping his ivory teeth, and surveyed the mob with the air of a prince.

Happily a car came to the rescue and the driver fairly lifted him on board.

"By my sowl thin, and its the divil's own weight he is," said the fellow, as we drove off amid the cheers of the ragged crowd.

At the door I was met by my landlady herself. Now this tidy little woman had but one fault — her excessive and tiresome cleanliness. She appeared without her eternal dust-rag, with which she kept flick-ilicking everything, always and everywhere. Born she must have been with a broom in her mouth. Dust dared not float, far less lie in her rooms. Flies, as a rule, avoided the house, or if one unwarily intruded, it was followed, stalked, and dodged, and finally killed, and triumphantly marched off with on a japanned shovel. I brushed past her as quickly as possible with Nero.

"Thonomon diaoul!" I heard her exclaim, as I made my way to the back-door. "I'm spacheless, Och! and ain't I clane claning after ye for ever-more, and haven't ye a cat and a canary, a rat and a rabbit, and an unholy baste in a bottle av whiskey, besides a box full av butterflies, and now you've brought me a calf. Och, wurra, wurra, it'll be the death of me entirely."

"Hush! hush!" cried I. "Didn't your father keep a pig in his parlour?"

"Is it the pig?" was her answer "the crature! And sure, wasn't it dacint and human then?"

This was the first and last scene about Nero with the "widder of poor Paddy McKoy," as she pathetically styled herself, and (I merely mention the fact to show the extreme cleanliness of this breed of dog when properly tended) before a fort-night was over he had the run of the house, and slept nightly at my bedroom door.

Owing to the thickness of his coat, I doubt if there is any dog that requires more careful grooming than the Newfoundland; that is, if he is to be man's companion and servant, as nature intended he should be. These dogs are very cleanly in their habits, and fleas do not readily gather on them, as on smaller dogs. It seems indeed to be a provision of nature that all large animals should be exempt from this fidgetty insect, else how could man come in contact at all with either the horse or cow. There are different ways of grooming the Newfoundland. Some brush them, some wash them. I do both, using a hard brush every morning, and having him carefully washed once a week with hard soap and water. Eggs would be preferable to soap I allow, but it would require the produce of nearly a dozen fowls to do him justice; and I rather suspect the gallant commander of our ship might object to see these feathered gentry strutting up and down his snow- white quarterdeck. If in good health and properly groomed, a Newfoundland dog ought to smell as sweetly as a lady's muff.

The first grooming that Nero had was a very laborious business. The puppy hair, burned red in his transatlantic voyage, stuck on end all over his back. Every bit of it came away with the first combing, as much as would stuff a decent-sized arm-chair for one's grandmother. Then he had a tub and a scrub, and when dry I thought more of my present than ever.

For days after he came into my possession, Nero mourned for his old master, refusing all food, and not replying to my caresses. However, I liked him all the better for this, and by degrees he came round; and now, like a true Newfoundland, he obeys no one but myself.

But the evil time was drawing nigh for him, and a trying time, although it was the means of displaying many of the best of his qualities. About six weeks after his landing he began to get less frisky, ate less and less every day, till at last he refused all food. At the same time his coat lost its silky gloss and stood on end, his bright eyes grew dull, and I knew from experience that he was to all intents and purposes plague-stricken. Distemper was in his blood. What lover of dogs does not know that dreadful disease — the scourge of the canine race? Who has not marked with sorrow the gradually wasting form of his poor favourite, who no longer bounds to greet his coming; his blood-shot, mattery eyes, his quick and heated breathing passing on to all the symptoms of dysentery and inflammation of lungs combined!

For two months nothing entered poor Nero's mouth except what was put there by the spoon. If any reader has a dog in distemper whose life he would save, let him send for a veterinary surgeon of skill, — for few among them know much of dog diseases, — let him treat the poor animal rationally, and he will probably recover. Distemper is to be treated much the same as typhus fever in the human being, — every symptom attended to, and every complication watched and combated on appearing. To attempt to cure distemper by any of the so-often-advertised and never-to-be-too-much-condemned nostrums of the quack, would meet with as much success, and merit as little, as a band of schoolboys with pop-guns attempting to stem the charge of a body of Prussian Uhlans.

Nero's patience, under his terrible sufferings, was quite affecting to behold. The crisis came at last, and he lived. Then the genial days of spring, and long walks into the country, soon set him on his legs again, and banished even the dregs of the disease; and he never has had a day's sickness since, unless I may say once, when, for a whole week, he turned up his nose at his dinner, being in fact very deeply in love; and what made the thing more ridiculous was, that the object of his affections was a black-and-tan toy terrier, under five pounds weight. This small lady was travelling with her mistress, and sojourned for a fortnight at an hotel. Whenever I went out Nero started from my side, and sure lover never yet hied him to the presence of lady-love with the swiftness he sped to his. He galloped off at such a rate as to be scarcely visible, leaving me to follow at my leisure, certain of finding him at the hotel.

Nor was this reckless race of his unattended with danger to the lieges. One morning, a peaceful baker crossed his track, and in a moment he lay prone, his loaves were scattered to the four winds of heaven, while the basket continued the journey on its own account. Another day, an unfortunate mechanic with bag of tools turned a corner at an unlucky moment, and Nero ran through him, as it appeared to me, and the man bit the dust. However, this liaison of Nero's bore good fruits in the long run; had it not been for this, probably he would not now be lying at my feet. Going so often to the hotel as I had to, I thought myself in duty bound to call for something for the good of the house. The landlord was a very amusing old fellow, had been all through the Indian Mutiny, and could spin a very good yarn; so that it soon got to be a habit with me to drop in of an evening and smoke a cigar. One dark winter's evening, in one of the principal thoroughfares, I suddenly found I had lost my dog. It was in vain I hallooed and whistled; and although I waited fully half an hour, I saw him no more that night. It was all the more provoking, in that it was my own fault; I had gone into a shop while he was behind; he had missed me, and rushing past, disappeared in the darkness. Next morning early I was making the rounds of all the police stations; in fact, before evening I had driven over half the city to look at dogs which had been found during the night, and fully answered to the description of mine. In every case I was disappointed; and after advertising and ordering bills, I returned, tired and sad, to my now lonely rooms. The weather had changed during the day to snow, and in the quiet street where I lived it lay soft and clean at least five inches deep. This was lucky for me; for no sooner had I opened my door, than who should I meet but Nero himself. There was a fond cry, and rather much of a bound, for I immediately found myself on my back almost suffocated with the snow and the dog's caresses. To each of the tradesman's shops at which I dealt I afterwards found he had galloped in succession, and, muddy and breathless, he had arrived at my friend's, the hotel-keeper, at eleven o'clock, where he was kept for the night and sent home in the morning. Had I not changed my lodgings the very day I lost him, in all probability he would have found his way home.

Most Newfoundlands are easily taught to keep well in to heel. Nero is no exception; although, being young, the inclination to run and have a game of romps with another dog is sometimes irresistible, and brings its own punishment in the shape of moderate flagellation, for I think a dog can always be better ruled by words than blows.

During the last summer, which was very hot, there was one particularly crowded part of a street in Margate where I resided. Every day for several days, as I passed this spot, I missed the dog from my side; and just as I had given him up for lost, he appeared, looking peculiarly satisfied about something. On the fourth or fifth occasion I watched him, and, at the same spot, he stole quietly from my side, and rather to my surprise, I saw him slink into a gin palace at the corner, where, on entering, I found him enjoying, not a pint of beer, but a tumbler of water, and actually the man had put a lump of ice in it.

"Does he often come here?" said I.

"A regular customer," replied the man, "for a week back."

And so he continued. With few exceptions, dogs, I believe, care little for music. I play the violin indifferently well, and my last dog, a fine Labrador, never heard the strains of the instrument without throwing himself at my feet, where he remained entranced till I had finished, when he would rise, solemnly shake himself, and walk away. Nero, while evincing no regard for, is still tolerant of my performances, so far only as melody is concerned. Harmony he cannot bear; that is, it frightens him. For example, if I play chords along with the piece, he jumps up, snuffs at and closely examines the fiddle and my face with a most superstitious countenance, and finally barks me down, and gets turned outside the door. Street bands are his particular abomination. Pity the German band that blow up as he is passing. They are instantly and angrily dispersed, and more than once have I seen him single out one poor wretch, generally the trombone, give chase, and having pulled him to the ground by the coat-tails, return to me, shaking his tail, and looking very much ashamed apparently at having given vent to his wrath.

By the kind permission of our commander, Nero is allowed on board (H.M.S. Pembroke, Sheerness), where he leads a very happy life, going on shore daily for his run and his swim. He prefers the latter mode of going on shore to boating. He has been taught to make a bow, and never comes on board without duly saluting the quarter-deck in man-o'-war fashion. This making a bow is also handy in many ways. If you ask him if he is hungry or thirsty, as the case may be, a low bow is an answer in the affirmative. If very hungry a loud accompanying bark makes the answer more emphatic.

In the water the strength of this dog is prodigious. He swims fast and well, and high out of the water, and can support a man for any distance. Although Nero has not yet had the pleasure of garotting a thief, or saving a mamma's darling from the treacherous waves, he is a faithful watch-dog, brave even to a fault, and moreover seems to have the natural instinct to save life and property from the water. Without being told to, he swam out, through the breakers, and brought in a flag which he had seen blown into the sea. One day a retriever fell from an open port. Nero saw the accident from a boat, and at once leaped over-board, and swam towards him; he attempted to seize the dog by the neck, but all the thanks he got was a snarl and a bite, for his kind intention was misconstrued, and Sambo was as much at home in the water as he himself. Equally little thanks did he receive for one day paddling up to me, enjoying a pleasant swim, and in a quiet business-like manner attempting to pull me in by the shoulder.

Nero is a very gentlemanly dog. He never provokes a fight, nor plays the bully; yet, though good-tempered, terrible is the punishment of the dog who has incurred his displeasure.

Once, when a bull-dog that had fastened on his neck, could not be got rid of by any amount of shaking, Nero fell on him so heavily that the creature could barely crawl away, and his savage master, who had set him on, wanted damages from me because his "poor doggie had been spitting blood ever since, your honour."

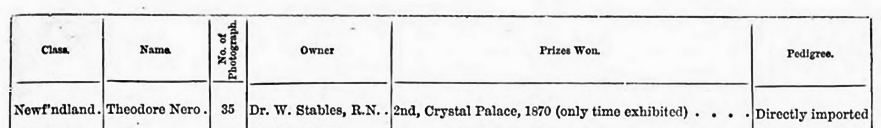

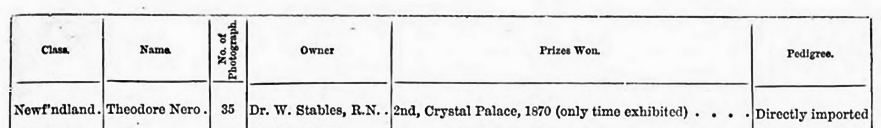

The other day a brown retriever, who had dared to seize Nero's stick in the water, after being well thrashed on the beach, was dragged into the water and lain upon. He must have swallowed pints of salt water, for he was nearly dead before I succeeded, at the expense of a thorough wetting, in dragging Nero off. Nero (35) has only as yet been once exhibited, viz., at Crystal Palace in 1870, where he gained the second prize.

In conclusion, Theodore Nero begs me to say that he is come of a very ancient and noble Newfoundland stock; but as registration is unknown in his otherwise favoured island, his pedigree is not come-at-able, which however he does not regret, as it gives him the glorious opportunity of becoming chief of his clan and founder of his family; and so he makes his bow to the British public — his bow with a bark.

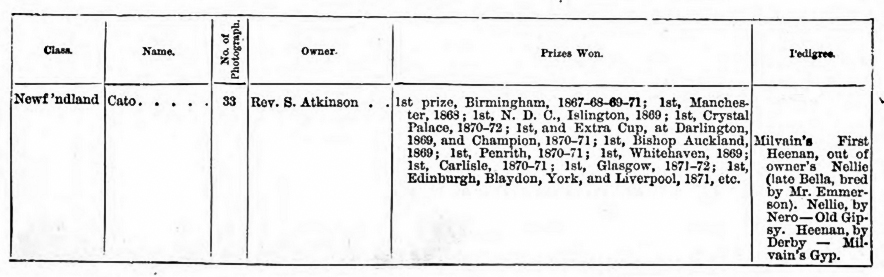

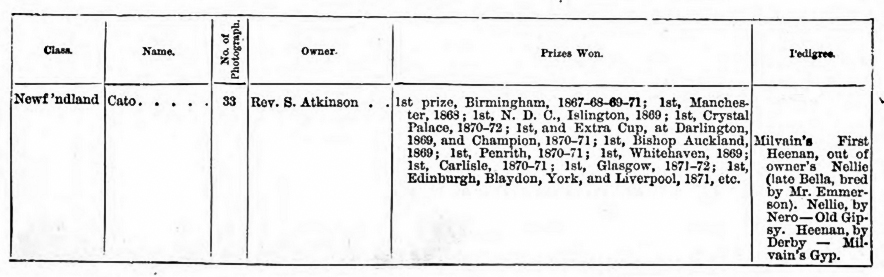

Of Cato (33) (the property of the Rev. S. Atkinson), winner of twelve first prizes, a second, and a third, the following interesting anecdote is given: — "Scarcely two months after this noble creature gained the first prize at the Crystal Palace Dog-show, in June, 1870, he gallantly rescued his master and a lady from a watery grave. On Monday, the 15th of August, about 4 o'clock in the afternoon, Mr. Atkinson was sitting with some friends on the sands at Newbiggin-by-the-Sea. There was a strong north-east wind blowing and heavy sea on, so much so, that the herring-boats rode at anchor in the bay. Four ladies went in to bathe; of these, two returned to the machine to dress, leaving two in the water; just then Mrs. Atkinson took her husband's walking stick to throw into the waves for Cato to bring out, and about a minute after a cry of distress arose. The two ladies, Mrs. W– and Miss G. F–, appeared to be struggling in the water, and crying for help. Mr. Atkinson, although unable to swim, and look- ing vainly for aid from other quarters, accordingly made his way to Mrs. W–, sometimes on his feet, and sometimes off them, as he got into the rough, or was lifted by the waves. After reaching Mrs. W–, he saw a boat approaching, which he afterwards learned was propelled by a long pole, as oars were not at hand at the moment. The boat was also helped on by a fair stern wind, and as it neared Miss G. F– a man held out the "tiller" of the boat to her, which she seized, leaving Mrs. W– and Mr. Atkinson still struggling in the water. Mr. Atkinson then tried for the shore, but Mrs. W– was exhausted, and he found himself unable to make way owing to the "sweep," under current" or "suck" seawards. then that he saw Cato for the first time, just at his left side, and throwing his left arm over the dog's shoulder, whilst he held Mrs. W– with his right, Cato set himself to work and swam them both out of danger. During this scene the excitement on shore had been intense, and the spectators observed that Cato, before going to his master, seized Mrs. W–'s bathing-dress twice, but the garment gave way each time. When the cry was first raised, the faithful dog was higher up on the shore with his mistress; no one called on him, no one sent him to the rescue; but Cato saw how matters stood, and with the brave instinct of a faithful Newfoundland, he became the preserver of two human lives."

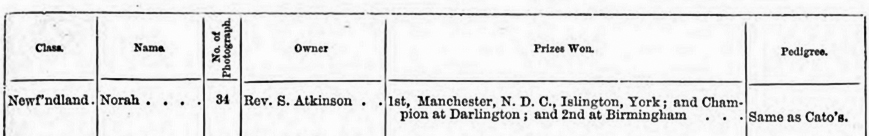

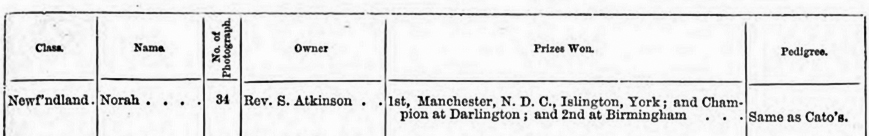

We also give a photograph of "Norah" (34) also the property of the Rev. T. Atkinson.

We have also another interesting anecdote here of the sagacity of a Newfoundland dog — "A vessel was driven by a storm on the beach of Lydd, in Kent. The surf was rolling furiously. Eight men were calling for help, but not a boat could be got off to their assistance. At length a gentleman came upon the beach, accompanied by his Newfoundland dog. He directed the attention of the noble animal to the vessel, and put a short stick in his mouth. The dog at once understood his meaning, and sprung into the sea, fighting his way through the foaming waves. He could not, however, get close enough to the vessel to deliver that with which he was charged; but the crew joyfully made fast a rope to another piece of wood, and threw it towards him. The sagacious dog saw the whole business in an instant; he dropped his own bit of wood, and immediately seized that which had been cast to him; and then, with a degree of strength and determination almost incredible, he dragged it through the surge, and delivered it to his master. By this means a line of communication was formed, and every man on board was saved."

In The Animal World of March, 1870, is contained a very affecting story of a Newfoundland, called Leo. This dog had taken a great fancy to an old farmer's wife, whom his master used to visit at times. She was equally fond of the animal. Leo one day delighted her much by taking a rabbit he had caught, placing it on her knee, and, with sundry knowing barks, begged her acceptance of it. At last the poor old lady, who was suffering from an incurable cancer, got worse — her time was at hand. Leoís master went one day and found there was much blood on the bed, a fresh artery in the wound having just burst. Leo was instantly shut out, as it was thought he would be much in the way. After a few words of condolence had been spoken, the old lady asked for Leo, at the same time groping about at the bedside for him. She was told he was outside, and that it was thought best not to have within. "Oh, let him come — let him come in just this once more."

His master opened the door thinking to have time to school Leo as to his conduct; but he slipped in at once, and instead of his usual demonstrations of delight at seeing his old friend, he solemnly walked to the bedside, and after a moment of seeming consideration, raised himself on it by his two forepaws, and stretching over to the fullest extent of his reach, most gently licked the poor face, which, half buried as it was, was very difficult to get to.

"Ah!" exclaimed Peggy, "there's likely none o'my own kind, or, for that matter, o' my own nearest kin, as would have been willing to kiss me as I am now."

There was a singular delicacy and tenderness in the manner of the dog as he performed this act, and then dropped quietly down by the side of the bed, there sitting motionless, his head hanging down, solemn and sad. On leaving the house, Leo, instead of his usual manner after a call, barking or jumping about, made no noise, crept quietly along after his master, head down, solemn and earnest. His favourite pond, where he was always wont to beg for his master's stick to be thrown in, was passed by without a thought. On reaching home he went straight to his kennel without a bark or sound. It was the last time he ever saw his poor old friend Peggy. Death claimed her as his own within a day or two from Leo's visit.

The head of a Newfoundland is remarkably grand and full of character, and its expression very benevolent. Across the eyes the skull is very broad, and he has a large brain. The forehead is frequently wrinkled; the eyes are small, but bright and intelligent. They are generally deeply set, but should not have a blood-shot appearance. The ears must be small, smooth, set low, and hanging close; they are very seldom set up, even when the animal is excited. Nose and nostrils large; muzzle long and quite smooth; mouth capacious; teeth level.

The neck is naturally short. It is, well clothed with muscle, as are the arms, legs, and fore-hand; but there is a slackness about the loin, which accounts for his slouching and somewhat slovenly carriage.

He is frequently short in his back ribs, and some of the largest dogs have a tendency to weakness in the back. The feet are long and strong, but the sole is not so thick as that of a well-bred pointer, nor are the toes so much arched as in the average of hunting dogs. This peculiar structure of the foot is adapted for his sledge work on snow, and accounts for his power in the water, and has given rise to the vulgar error that he is "semi-palmated." Owing to this structure, the dog has a wholesome dread of the down-thistle or of short furze.

The shaggy-coated Newfoundland has a smooth face, but within 2in. of the skull the coat suddenly elongates, and, except that he is very clean to the angle of his neck, he is thoroughly feathered in his outline. His coat generally parts down the back, and this parting is continued to the end of the tail, which is bushy and carried very gaily. His hind legs are close-coated from the hock, and his feet all round are nearly as free of feather as a catís.

The colour is generally black; and a brown, or brindled tinge, is a valued characteristic of the true breed. The black and white is not considered so good.

In form be is colossal. He has been known to reach 3tin. in height, and he is frequently to be found from 28in. to 30in., or even more.

| POINTS |

| Head |

. . . . . . . . |

20 |

| Eyes |

. . . . . . . . |

5 |

| Ears |

. . . . . . . . |

5 |

| Frame |

. . . . . . . . |

10 |

| Symmetry |

. . . . . . . . |

10 |

| Legs and Feet |

. . . . . . . . |

10 |

| Size |

. . . . . . . . |

20 |

| Coat |

. . . . . . . . |

10 |

| Colour |

. . . . . . . . |

10 |

(130 - 150)

The photos in this book are composite images, so each dog image is quite small. The images of Cato (#33) and Norah (#34), and Theodore Nero (#35) have been excerpted from the composite image. There are illustrations of a few breeds (mostly in the "Sporting Dog" section of this book), but there is no Newf illustration.

The final mention of Newfoundlands occurs in the chapter "Watch-Dogs":

One of the best watch-dogs you can have is, I think, the large white-and-black Newfoundland ; but he must on no account be kept always on chain. I believe, however, the best watch for yard or hall is a small well-trained terrier, with a large black Newfoundland, the former gives the alarm, and the latter does the fighting, or as a friend of mine says, the one rings the bell, and the other attends the door. (265)