[ Wickham / "Dogs of Noted Americans" ]

Gertrude Van Rensellaer Wickham (1844 - ?) was an American journalist and newspaper editor (the first woman to hold such a position in Cleveland, Ohio, on the Cleveland Herald) and author of a two-volume work on Ohio genealogy, though today she is best remembered for this essay on dogs owned by famous Americans. Researching her article, Wickham wrote to a number of well-known American cultural and political figures (or, in the case of those who were deceased, to surviving relatives or offspring.) While she was surprised to find that some of her literary idols — Ralph Waldo Emerson and Nathaniel Hawthorne, to name only two — had no love at all for dogs, she received a sufficient number of positive responses to produce a three-part article on famous dog-loving Americans. These pieces were published in St. Nicholas magazine, a popular children's magazine that ran from 1873 - 1940 and which attracted some of the best American writers of the time.

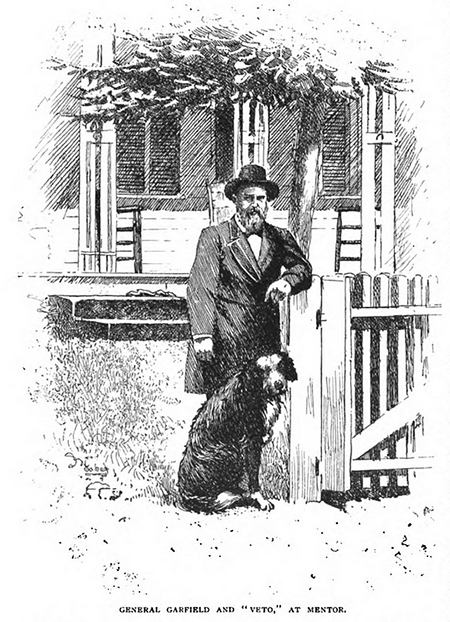

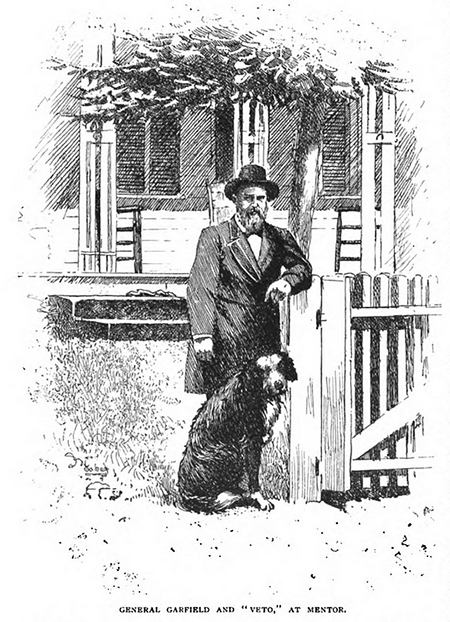

The very first entry in the first article is devoted to a Newfoundland named "Veto," who belonged to the U. S. President James Garfield (1831 - 1881). Garfield became the 20th President of the United States in March of 1881, but was assassinated only four months later. Born in Ohio, Garfield rose to the rank of general in the Union Army before entering politics.

This essay appeared in the June, 1888, issue of St. Nicholas.

GENERAL GARFIELD’S DOG.

In the summer of 1880, when the first delegation of enthusiastic politicians

came trooping up from the Mentor station through the lane that led to "Lawnfield," in order to congratulate General James A. Garfield on his nomination for the Presidency, there was one member of the Garfield household who met the well-meaning but noisy strangers with an air of astonishment and disapproval, and, as they neared the house, disputed further approach with menacing voice.

This was "Veto," General Garfield’s big Newfoundland dog; and not until his master had called to him that it was "all right," and that he must be quiet, did he cease hostile demonstrations.

After that, whenever delegations came — and they were of daily occurrence — Veto walked around among the visitors, looking grave and sometimes uneasy, but usually peaceful. General Garfield was very fond of large, noble-looking dogs. Veto was a puppy when given to him, but in two years' time had grown to be an immense fellow, and devotedly attached to his master. He was named in honor of President Hayes’s veto of a certain bill in the spring of 1879. The bill was one for abolishing the office of marshal at elections. It did not meet with the President’s approval, and he returned it to Congress unsigned, — an action which greatly pleased General Garfield, and suggested the name for his dog.

Although quiet, as he had been bidden, Veto was never reconciled to the public’s invasion of the Mentor farm. He was a dog of great dignity, and could not but feel resentment at the familiarity of the strangers who, on the strength of their political prominence, overran his master’s fields, spoiled the fruit-trees, peered into the barns and poultry yard, and were altogether over-curious and intrusive. He had been told that it was "all right"; but these actions by day, and the torchlights and hurrahing by night, wore on his spirits and

temper. This evident unfitness for public life caused a final separation from his beloved master; for when, in the following spring, the family moved to Washington to begin residence at the White House, they thought it was not best to take Veto with them, so he was left behind in Mentor.

Poor fellow! all his doubts and fears for the safety and peace of him he loved and guarded were indeed well-founded. That first invasion of Lawnfield was but the beginning of what was to end in great calamity and bitter sorrow. Veto never saw his master again.

After the death of General Garfield, Veto was taken to Cleveland, O., where he spent his remaining days in the family of J. H. Hardy — a gentleman well known in that city.

Several anecdotes are related by Mr. Hardy which prove the dog’s great intelligence. He slept in the barn, and seemed to consider himself responsible for the proper behavior of the horses, and the safety of everything about the barn. No one not belonging to the family was allowed even to touch any article in it. Veto’s low thunder of remonstrance or dissent quickly brought the curious or meddlesome to terms.

One night he barked loudly and incessantly. Then, as this alarm signal passed unnoticed, he howled until Mr. Hardy was forced to dress and go to the barn, where he found a valuable horse loose and on a rampage. Veto had succeeded in seizing the halter, and there he stood with the end in his mouth, while the horse, disappointed of his frolic and his expectation of unlimited oats, was vainly jerking and plunging to get away.

Another time, upon returning late at night from a county fair, the family heard Veto — who was shut up in the barn — howling and scratching frantically at the door. When it was opened, he rushed directly to another barn some rods away, belonging to and very near a house occupied by a large family, who all were in

bed and asleep. He scratched at the door of this barn, keeping up at the same time his dismal howl, and paying no attention to the repeated calls and commands to "come back and behave" himself. Just as force was to be used to quiet him, a bright tongue of flame shot up through the roof of the barn, and, almost in an instant, the whole structure was in a blaze. Before the fire department reached the spot the barn was consumed, and the house was saved from destruction only through heroic efforts of the neighbors.

And so Veto's quick scent and wonderful sagacity in, as we must believe, giving the alarm, not only saved the house, but probably averted serious loss of life. (595 - 596)

The third and final installment of "Dogs of Noted Americans" appeared in the May, 1889, issue of St. Nicholas. One of the dogs appears, both from the illustration (which the magazine notes were made from photographs) and from the dog's behavior, to be a Newfoundland (or possibly a Newf mix), though the breed of the dog is never specifically mentioned. The owner of this dog was David Dixon Porter (1813 - 1891), an admiral in the U. S. Navy and a member of one of the Navy's most prominent families.

ADMIRAL PORTER'S DOG "BRUCE"

ALL boys who love the water, and especially those who think that they would like to be sailors, will be interested in "Bruce," once the favorite dog of Admiral David D. Porter, of our Navy.

Dogs have been favorites with the Admiral all his life, and within the last twenty years, or since making Washington his headquarters, he has owned no less than twenty-two!

But Bruce, early in his career, earned the high est place in his master's regard by one of those feats of sagacity which seem to prove that animals sometimes reason, and that, too, often more wisely than their recognized mental superiors.

Admiral Porter had a little grandson, who lived near a deep and rapid water-course about twenty five feet wide. The stream was crossed by a narrow plank. One day, the little fellow — who was but three years of age — attempted the perilous crossing alone. There was no one near to warn him of danger or prevent him but the dog. Realizing the child's peril, Bruce ran to him, and, catching hold of his dress, tried to pull him back. The youngster was determined to have his own way, and vigorously resented the dog's interference by beating poor Bruce in the face, with a big stick he carried, until the dog was forced by pain to relinquish his hold.

The faithful animal then jumped into the water, and swam slowly across the stream, below the plank, evidently with the intention of saving the child, should he happen to fall in.

When they were both safely across, and Bruce had shaken the water from his shaggy coat, he artfully induced the little fellow to get on his back for a ride, a treat he knew the youngster much enjoyed and for which he was always ready.

The moment the dog felt the child's arms around his neck, and the little feet digging into his sides, he trotted back across the plank, and homeward, never stopping until his young charge was safely beyond any temptation of repeating his dangerous performance.

Bruce was a famous watch-dog, and guarded the Admiral's premises in Washington more effectively than any night-watchman, for it would have taken more courage to confront him than to encounter any average watchman. He weighed one hundred and seventy-five pounds, and was very large around the body. His hair was long, shaggy, and of a dark drab color, except upon his neck, breast, and feet, where it was pure white; and he was noted among those who knew him for his gentle, expressive eyes.

Poor Bruce met his death in rather an ignominious way. Despite his bravery and sagacity, he possessed a weakness that in the end cost him his life. He would overeat! We can best try to excuse him for this by the supposition that living in Washington, a city so given to feasting and good living, had its effect on a dog prone to observation and emulation.

One day he gained access to a tub which, from a dog's standpoint, contained something so exceedingly good, that he ate the entire contents. Perhaps some other dog stood by, hoping to share the meal, or awaiting a possible surplus — a state of affairs that always serves to lend added relish to a canine feast. A rush of blood to the head, fol lowing close upon this foolish overindulgence, unfortunately proved fatal. (543 &mdash 544)

You may find many more well-known Newfoundland owners listed here at The Cultured Newf.