[ Wood / The Illustrated Natural History ]

The Rev. John George Wood (1827 - 1889) was an English writer, lecturer, and science popularizer, primarily on zoological subjects. He also edited the popular Boys Own Magazine.

This large, 3-volume work was published 1859 - 1863 in London by Routledge, Warne, and Routledge. It was later revised and published as Animate Creation in 1895.

The first mention of Newfoundlands in this book occurs in a discussion of Howler monkeys, particularly of the shipboard transport of a female Howler monkey named Sally:

She seemed to bear the cold weather tolerably well, and was supplied with plenty of warm clothing which stood her in good stead even off the icy coasts of Newfoundland, where, however, she expressed her dislike of the temperature by constant shivering. In order to guard herself against the excessive cold, she hit upon an ingenious device. There were on board two Newfoundland dogs. They were quite young, and the two used to occupy a domicile which was furnished with plenty of straw. Into this refuge Sally would creep, and putting an arm round each of the puppies and wrapping her tail about them, was happy and warm.

She was fond of almost all kinds of animals, especially if they were small, but these two puppies were her particular pets. Her affection for them was so great, that she was quite jealous of them, and if any of the men or boys passed nearer the spot than she considered proper, she would come flying out of the little house, and shake her arms at the intruders with a menacing gesture as if she meant to bite them. (89)

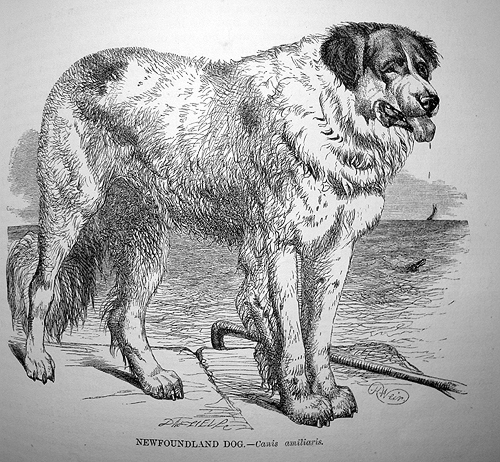

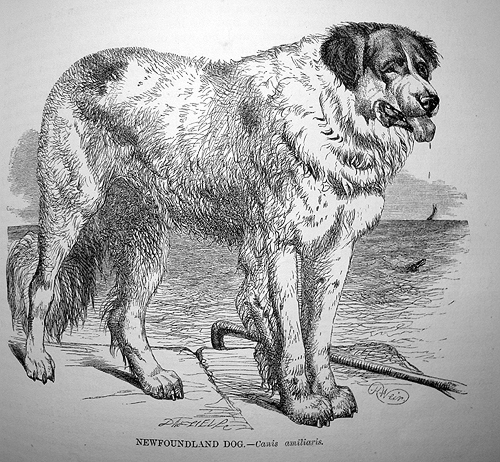

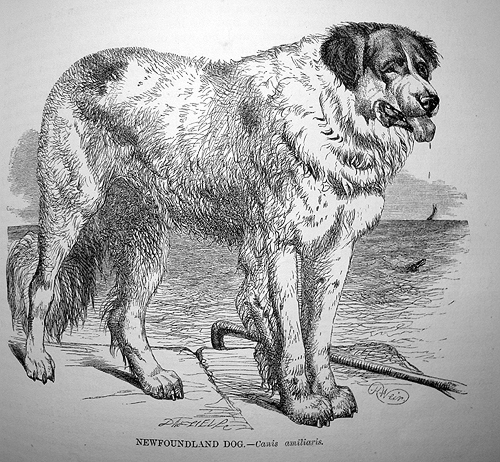

The primary discussion of Newfoundland dogs (Vol I, pp 263 - 266) consists to some degree of anecdotes from earlier books that treat of the Newfoundland. This chapter includes the following illustration of a Newfoundland dog, engraved by one of the Dalziel brothers (noted London engravers of the mid-19th Century) from a drawing by Harrison Weir (1824 - 1906), the noted English animal illustrator who, according to his Wiki entry, is also known as "the Father of the Cat Fancy" for organizing the very first cat show in England in 1871.

This illustration surely is indebted to Sir Edwin Landseer's A Distinguished Member... (1839) for its portrayal of a Landseer Newf on a stone quay. This image is not reproduced in the revised version of this book. Note the drool — this is the earliest reference I have found to Newf drool:

The large and handsome animal which is called from its native country the NewfoundLand Dog, belongs to the group of spaniels, all of which appear to be possessed of considerable mental powers, and to be capable of instruction to a degree that is rarely seen in animals.

In its native land the Newfoundland Dog is shamefully treated, being converted into a beast of burden, and forced to suffer even greater hardships than those which generally fall to the lot of animals which are used for the carriage of goods or the traction of vehicles. The life of a hewer of wood is proverbially one of privation, but the existence of the native Newfoundland Dog is still less to be envied, being that of a servant of the wood-hewer. In the winter, the chief employment of the inhabitants is to cut fuel, and the occupation of the Dogs is to draw it in carts. The poor animals are not only urged beyond their strength, but are meagrely fed with putrid salt fish, the produce of some preceding summer. Many of these noble Dogs sink under the joint effects of fatigue and starvation, and many of the survivors commit sad depredations on the neighboring flocks as soon as the summer commences, and they are freed from their daily toils.

In this country, however, the Newfoundland Dog is raised to its proper position, and made the friend and companion of man. Many a time has it more than repaid its master for his friendship, by rescuing him from mortal peril.

Astrologically speaking, the Newfoundland Dog must have been originated under the influence of Aquarius, for it is never so happy as when dabbling in water, whether salt or fresh, and is marvellously endurant of long immersion. There are innumerable instances on record of human beings rescued from drowning by the timely succor brought by a Newfoundland Dog, which seems fully to comprehend the dire necessity of the sufferer, and the best mode of affording help. A Dog has been known to support a drowning man in a manner so admirably perfect, that if it had thoroughly studied the subject, it could not have applied its aiding powers in a more correct manner. The Dog seemed to be perfectly aware that the head if the drowning man ought to be kept above the water, and possibly for that purpose shifted its grasp from the shoulder to the back of the neck. It must be remembered, however, that all Dogs and cats carry their young by the nape of the neck, and that the Dog might have followed the usual instinct of these animals.

Not only have solitary lives been saved by this Dog, but a whole ship's crew have been delivered from certain destruction by the mingled sagacity and courage of a Newfoundland Dog, that took in its mouth a rope, and carried it from the ship to the shore.

Even for their own amusement, these Dogs may be seen disporting themselves in the sea, swimming boldly from the land in pursuit of some real or imaginary object, in spite of "rollers" and "breakers" that would baffle the attempts of any but an accomplished swimmer. Should a Newfoundland Dog be blessed with a master as amphibious as itself, its happiness is very great, and it may be seen splashing and snapping in luxuriant sport, ever keeping close to its beloved master, and challenging him to fresh efforts. It is very seldom that a good Newfoundland Dog permits its master to outdo it in aquatic gambols. The Dog owes much of its watery prowess to its broad feet and strong legs, which enable the creature to propel itself with great rapidity through the water.

As is the case with most of the large Dogs, the Newfoundland permits the lesser Dogs to take all kinds of liberties without showing the least resentment; and if it is worried or pestered by some forward puppy, looks down with calm contempt, and passes on its way. Sometimes the little conceited animal presumes upon the dignified composure of the Newfoundland Dog, and, in that case, is sure to receive some quaint punishment for its insolence. The story of the big Dog, that dropped the little Dog into the water and then rescued it from drowning, is so well known that it needs but a passing reference. But I know of a Dog, belonging to one of my friends, which behaved in a very similar manner. Being provoked beyond all endurance by the continued annoyance, it took the little tormentor in its mouth, swam well out to sea, dropped it in the water and swam back again.

Another of these animals, belonging to a workman, was attacked by a small and pugnacious bull-dog, which sprang upon the unoffending canine giant, and, after the manner of bulldogs, "pinned" him by the nose, and there hung, in spite of all endeavors to shake it off. However, the big Dog happened to be a clever one, and spying a pailful of boiling tar, he bolted towards it, and deliberately lowered his foe into the hot and viscous material. The bull-dog had never calculated on such a reception, and made its escape as fast as it could run, bearing with it a scalding memento of the occasion.

The attachment which these magnificent Dogs feel towards mankind is almost unaccountable, for they have been often known to undergo the greatest hardships in order to bring succor to a person whom they had never seen before. A Newfoundland Dog has been known to discover a poor man perishing in the snow from cold and inanition, to dash off, procure assistance, telling by certain doggish language of its own of the need for help, and then to gallop back again to the sufferer, lying upon him as if to afford vital heat from his own body, and there to wait until the desired assistance arrived.

I might multiply anecdote upon anecdote of the wondrous powers of this spirited animal, but must pass on to make room for others.

There are two kinds of Newfoundland Dog; one, a very large animal, standing some

thirty-two inches in height; and the other, a smaller Dog, measuring twenty-four

or twenty- five inches high. The latter animal is sometimes called the Labrador

Dog, and sometimes is termed the St. John's Dog. When crossed with the setter,

the Labrador Dog gives birth to the Retriever. The large Newfoundland is generally

crossed with the mastiff.

There are few Dogs which are more adapted for fetching and carrying than the

Newfoundland. This Dog always likes to have something in its mouth, and seems

to derive a kind of dignity from the conveyance of its master's property. It

can be trained to seek for any object that has been left at a distance, and being

gifted with a most persevering nature, will seldom yield the point until it has

succeeded in its search.

A rather amusing example of this faculty in the Newfoundland Dog has lately come before my notice.

A gentleman was on a visit to one of his friends, taking with him a fine Newfoundland Dog. Being fond of reading, he was accustomed to take his book upon the downs, and to enjoy at the same time the pleasures of literature and the invigorating breezes that blew freshly over the hills. On one occasion, he was so deeply buried in his book, that he overstayed his time, and being recalled to a sense of his delinquency by a glance at his watch, hastily pocketed his book, and made for home with his best speed.

Just as he arrived at the house, he found that he had inadvertently left his gold-headed cane on the spot where he had been sitting, and as it was a piece of property which he valued extremely, he was much annoyed at his mischance.

He would have sent his Dog to look for it, had not the animal chosen to accompany a friend in a short walk. However, as soon as the Dog arrived, his master explained his loss to the animal, and begged him to find the lost cane. Just as he completed his explanations, dinner was announced, and he was obliged to take his seat at table. Soon after the second course was upon the table, a great uproar was heard in the hall; sounds of pushing and scuffling were very audible, and angry voices forced themselves on the ear. Presently, the phalanx of servants gave way, and in rushed the Newfoundland Dog, bearing in his mouth the missing cane. He would not permit any hand but his master's to take the cane from his mouth, and it was his resistance to the attempts of the servants to dispossess him of his master's property that had led to the skirmish.

It has been mentioned that the Newfoundland Dog is employed during the winter months in dragging carts of hewn wood to their destination, and that it is unkindly treated by the very men who derive the most benefit from its exertions.

There are a few other references to Newfoundlands in this volume, most of them incidental; the following are the most substantive. The first concerns a swimming race between a bulldog and a Newfoundland:

In all tasks where persevering courage is required, the Bull-dog is quietly eminent, and can conquer many a Dog in its own peculiar accomplishment. The idea of yielding does not seem to enter his imagination, and he steadily perseveres until he succeeds or falls. One of these animals was lately matched by his owner to swim a race against a large white Newfoundland Dog, and won the race by nearly a hundred yards. The owners of the competing quadrupeds threw them out of a boat at a given signal, and then rowed away as fast as they could pull. The two Dogs followed the boat at the best of their speed, and the race was finally won by the Bull-dog. It is rather remarkable that the Bull-dog swam with the whole of his head and the greater part of his neck out of the water, while the Newfoundland only showed the upper part of his head above the surface. (306)

The last is attributed to a Mrs S. C. Hall, and in part concerns her family's Newfoundland, Neptune:

"In our large, rambling, country home, we had Dogs of high and low degree, from the silky and sleepy King Charles down (query, up ?) to the stately Newfoundland, who disputed possession of the top step — or rather platform to which the steps led — of the lumbering hall-door with a magnificent Angora ram, who was as tame and almost as intelligent as Master Neptune himself. After sundry growls and butts the Dog and the ram generally compromised matters by dividing the step between them, much to the inconvenience of every other quadruped or biped who might desire to pass in or out of the hall.

. . . .

"Neptune, the ram's antagonist, had a warm friendship for a very pretty retriever, Charger by name, who, in addition to very warm affections, possessed a very hot temper. In short, he was a decidedly quarrelsome Dog; but Neptune overlooked his friend's faults, and bore his ill-temper with the most dignified gravity, turning away his head, and not seeming to hear his snarls, or even to feel his snaps.

"But all Dogs were not equally charitable, and Charger had a long-standing quarrel with a huge bull-dog, I believe it was, for it was ugly and ferocious enough to have been a bulldog, belonging to a butcher,—the only butcher within a circle of five miles. He was very nearly as authoritative as his bull-dog. It so chanced that Charger and the bull-dog met somewhere, and the result was that our beautiful retriever was brought home so fearfully mangled that it was a question whether it should not be shot at once, everything like recovery seeming impossible.

"But I really think Neptune saved his life. The trusty friend applied himself so carefully to licking his wounds, hanging over him with such tenderness, and gazing at his master with such mute entreaty, that it was decided to leave the Dogs together for that night. The devotion of the great Dog knew no change; he suffered any of the people to dress his friend's wounds, or feed him, but he growled if they attempted to remove him. Although after the lapse of ten or twelve days he could limp to the sunny spots of the lawn—always attended by Neptune—it was quite three months before Charger was himself again, and his recovery was entirely attributed to Neptune, who ever after was called Doctor Neptune — a distinction which he received with his usual gravity.

" Now here I must say that Neptune was never quarrelsome. He was a very large liver-colored Dog, with huge, firm jaws, and those small cunning eyes which I always think detract from the nobility of the head of the Newfoundland; his paws were pillows, and his chest broad and firm. He was a dignified, gentlemanly Dog, who looked down upon the general run of quarrels as quite beneath him. If grievously insulted, he would lift up the aggressor in his jaws, shake him, and let him go — if he could go — that was all. But in his heart of hearts he resented the treatment his friend had received.

"So when Charger was fully recovered, the two Dogs set off together to the Hill, a distance of more than a mile from their home, and then and there set upon the bull-dog. While we were at breakfast, the butler came in with the information that something had gone wrong, for both Neptune and Charger had come home covered with blood and wounds, and were licking each other in the little stable. This was quickly followed by a visit from the butcher, crying like a child—the great rough-looking bear of a man—because our Dogs had gone np the Hill and killed his pup 'Blue-nose.' 'The two fell on him,' he said, 'together, and now you could hardly tell his head from his tail.' It was a fearful retribution ; but even his master confessed that 'Blue-nose' deserved his fate, and every cur in the country rejoiced that he was dead." (318-319)