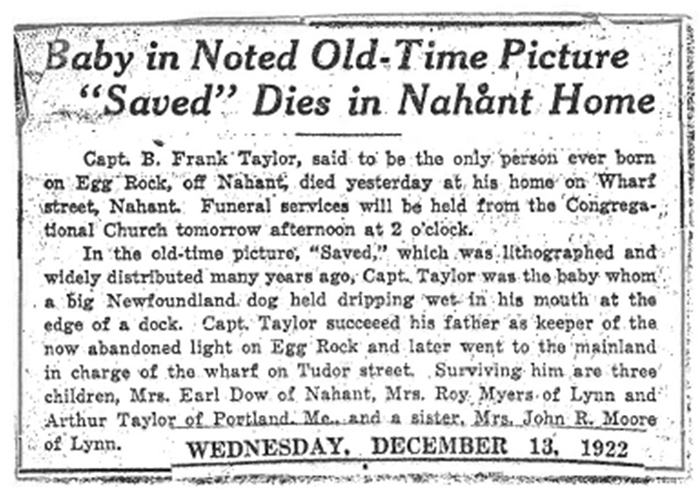

Saved

Saved (1856)

by

Sir Edwin Landseer

This painting is said by some to be the last of Landseer's Newfoundland depictions (although that is not accurate if Well-Bred Sitters Who Never Say They are Bored [1864] does indeed depict a Newfoundland, though that is uncertain.) Regardess, it is indeed a dramatic presentation by Landseer (1802 - 1873) of a scenario that powerfully combines Victorian ideas of animal nobility and sagacity with a sentimentalized construction of childhood, although "Saved" cannot be said to be his most effective dog painting. Writing for the prestigious arts and culture journal The Atheneum, an anonymous reviewer of a Landseer retrospective, held a little over a year after the artist's death, had this to say:

. . .we have in Saved the large painting of a dog, with a child lying before it across its paws; a work which is too evidently lamp-born to be particularly acceptable. The dog is, of course, fine, but the child, which has been rescued from the sea, is quite dry, and sleeps heartily. The landscape is cruder than usual, and the dog's paws are too big. (January 17, 1874, p. 99)

While it's certainly possible to quibble with the assertion the child is sleeping "heartily" — he or she (very young male children often wore, in 19th Century Britain, clothing that appeared feminine) may well be unconscious — there's no question the clothing appears dry even though the dog's strained look and apparent panting indicate the rescue has just recently been effected, and the dog looks none too wet either. Nor was Landseer's treatment of the paws up to his usual standard of accuracy; they are indeed too large, extend too far forward from the dog, and are at an odd angle relative to the dog's body.

It should also be noted that there is some speculation that this dog is not a pure-bred Newfoundland, but a St. Bernard / Newf cross.

Regardless of all of this, it is precisely because of this work's depiction of a noble creature in service of humanity — an idea that appealed very powerfully to the Victorians — that this work was quite popular in the mid- to late-19th Century, and appeared in many forms. Below is a lithograph of Saved produced by the renowned American printmaking firm of Currier & Ives:

By some accounts, Landseer's painting is based, loosely, on an actual Newfoundland named Milo, who came to fame when he rescued one of his family's children from the water, an event that Landseer got word of and which inspired him to paint this work, although he depicted the rescuing dog as a black-and-white Newf, while the real Milo was a black. Some have taken this to indicate that other paintings of early Newfoundlands may have been similarly "altered" for artistic effect (the black-and-white coat being more visually dramatic, and perhaps easier to paint well, than a solid black coat). For a bit more on Milo, check out this page at the Nahant (Massachusetts ) Historical Society. The following note about Milo and this painting appeared in the February, 2020, issue of the NCA's "e-Notes" newsletter:

Many Newfoundland fanciers and art buffs are familiar with the work of Sir Edwin Landseer, who popularized the white/black coloring in the Newfoundland breed. Some have even gone so far as to suggest that his prolific number of paintings of the white/black Newfoundland leads to the conclusion that that coloration was more prominent than the black at that period of time. In 1856 the Royal Academy exhibited "Saved." This painting is beautifully composed and it became as popular as "A Distinguished Member." It was based on the fame of Milo, a Newfoundland living with the keeper of the Egg Rock Lighthouse in Nahant, George B. Taylor. In foggy weather Milo served as a kind of fog signal, barking at vessels as they approached Egg Rock. Taylor claimed his dog was as useful as the light. Milo was credited with the rescue of several children from drowning around the island. His fame spread across the Atlantic. Landseer painted Milo’s portrait, depicting a small child nestled between the dog's enormous paws. An exhibit by the Nahant Historical Society shows this photograph of Milo with the Taylor family, posed on Egg Rock, and we see that Milo was indeed a black Newfoundland, and Sir Edwin had taken artistic license to depict him as white/black.

The above-mentioned article at the Nahant Historical Society states plainly that Landseer used Milo as the model for the dog in this painting — "Sir Edwin Henry Landseer painted Milo’s portrait" — and goes even further by including the following brief obituary:

It is not clear to me how Sir Edwin Landseer would have been able to use Milo as a model for the dog, unless the family sent him a photograph or travelled with the dog to London, for Landseer never visited America. And obviously "Saved," with its black-and-white dog, cannot be a "portrait" of the all-black Milo. I also suspect that when the newspaper obituary notes that Capt. Taylor "was the baby" who was rescued, the meaning is not that Taylor was the model for the child, but that Taylor was the young member of the family which Milo rescued from the sea and thus served only as general inspiration for the painting. (Note also the errors in the obituary: the "baby" is most certainly not held in the dog's mouth, and dog and child appear to be on a quay or on the shore, not a dock.)