[ Jackson / Our Dumb Companions ]

Thomas Jackson (1812 - 1886) was an English minister and author of several books of religious works and at least as many books about animals.

Our Dumb Companions; or, Conversations of a Father with His Children, about Dogs, Horses, Donkeys, and Cats was first published in 1860?) (London: S. W. Partridge), with several subsequent editions. Text below is from the second (1863?).

With one exception, all of the illustrations in this work are by Harrison Weir (1824 - 1906), the noted English animal illustrator who, according to his Wiki entry, is also known as "the Father of the Cat Fancy" for organizing the very first cat show in England in 1871. (It should be noted that the list of illustrations in this volume does not fully correspond to the images actually included.)

Newfoundlands are mentioned a number of times in this moralizing work, usually in re-worked versions of previously-published anecdotes. The first mention comes just after the children have heard an account of a sheepdog protecting a flock:

George. "That does one's heart good," as a great poet said, when he was reading his own poetry. But I am sure that it is not a finer example of dog genius, than many instances of sagacity in Newfoundland dogs which are on record.

Mary. Yes, what an exquisite picture is this of a Newfoundland dog saving the life of a little child! Some mother's bairn, though unknown to us!

Papa. Oh, no — not unknown. I can tell you all about it. A little girl named Lucy, the daughter of a rich gentleman, was playing one day on the lawn in front of her father's beautiful house, when she unfortunately ran too near the fish-pond, and fell in. Her mother was looking out of the drawing-room window, and saw Lucy sinking in the water. She screamed out to the servants, and they all rushed towards the pond, but as it was some distance from the house, they feared that poor Lucy would be drowned before they could reach her. A kind Providence, however, had interposed in her behalf. Bobby, a favourite dog, had plunged into the pond, and was struggling nobly to hold her up, and keep her head above the water. He howled for assistance. The servant-man soon arrived, and, grasping her arm, brought her safely to shore. She was carried to bed, and warm flannels were applied to her body. When the doctor arrived, he felt her pulse, and said she would soon be well. Tears of joy were in every eye when these words were spoken. When the parents came down stairs, who should be waiting at the bottom, but brave Bobby, wagging his tail. He got pats and kind words without number. Even the old housekeeper, who had a great aversion to dogs, could not help saying that she loved him, he was such a "good fellow," and she took care to give him a better supper than usual. Bobby was now the constant companion of Lucy, and she called him her DELIVERER. One day Lucy was sitting in the garden with Bobby by her side, when her mother came up and said, "What makes you love Bobby so much, my dear?" "Oh, mother! because he saved me from death." "Right, my child, I wish you to love him, but I am much more anxious that you should love and serve THE GREAT DELIVERER, who gave His life to save you. Can you tell me, my child, whom I mean?" "Yes, mother, JESUS, who died on the cross to save sinners." "Let us pray every day," continued the mother, "that we may be enabled to attend to the words of our dear Redeemer — 'If ye love me, keep my commandments.'"

George. I have a whole budget of strange adventures. Here is one: —

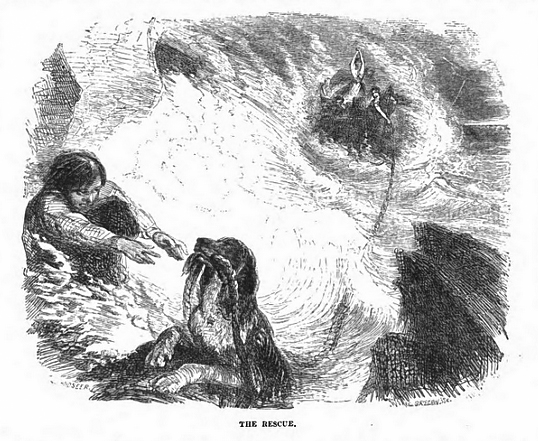

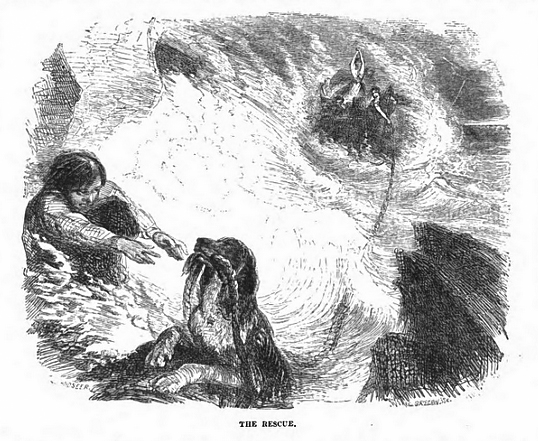

A gentleman connected with the Newfoundland fishery was once possessed of a dog of singular fidelity, and sagacity. On one occasion a boat and a crew in his employ were in circumstances of considerable peril, just outside a line of breakers, which, owing to some change in wind or weather, had, since the departure of the boat, rendered the return passage through them most hazardous. The spectators on shore were quite unable to render any assistance to their friends afloat. Much time had been spent, and the danger seemed to increase rather than diminish. Our friend the dog, looked on for a length of time, evidently aware of there being a great cause for anxiety in those around. Presently, however, he took to the water and made his way through the raging waves to the boat. The crew supposed he wished to join them, and made various attempts to induce him to come on board; but no, he would not go within their reach, but continued swimming about a short distance from the boat. After a while, and several comments on the peculiar conduct of the dog, one of the hands suddenly divined his apparent meaning:

"Give him the end of a rope," he said, "that is what he wants."

The rope was thrown, the sagacious dog seized the end of it in an instant, then turned round, and made straight for the shore. In a few minutes the dog reached the rocks. A sturdy fisherman dashed into the surf, and dragged the rope to land. The passengers and crew then got into the boat, and by means of the rope were all speedily drawn by the villagers safely to shore. No wonder that the rescued ones, after thanking God for their providential deliverance, were loud in their praises of their four-footed friend. Some of the passengers would gladly have purchased the splendid animal, but the worthy owner would not part with his dog for any amount of money.

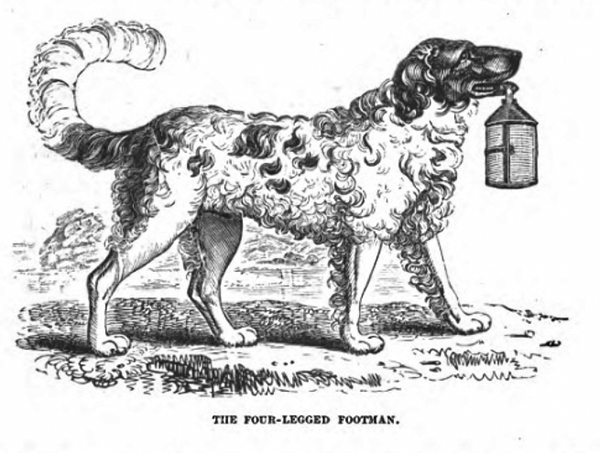

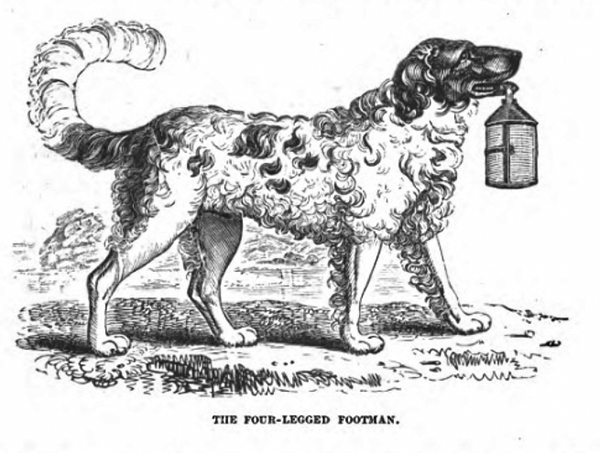

The upcoming anecdote about the dog and the lantern is another previously-published anecdote, this time including another Harrison Weir illustration that looks to me as though it owes something to Philip Reinagle's 1803 illustration of a Newfoundland. Jackson's version of this story makes only slight changes to the original text, which is Lewis Anspach's A History of the Island of Newfoundland (1819).

Papa. One of the magistrates of Harbour-Grace, in Newfoundland, had an old dog of the species peculiar to that island, who was in the habit of carrying a lantern before his master at night, as steadily as the most attentive servant could do, stopping short when his master made a stop, and proceeding when he saw him disposed to follow him. If his master was absent from home, and the lantern being fixed in his mouth, the command was given, "Go, fetch thy master," he would immediately set off, and proceed directly to the town, which lay at the distance of more than a mile from the place of his master's residence; he would then stop at every house which he knew that his master was in the habit of frequenting, and laying down his lantern, would growl, and strike the door, making all the noise in his power until it was opened; if his master was not there, he would proceed farther, in the same manner, until he had found him. If he had accompanied him only once into a house, this was sufficient to induce him to take that house in his round. (23 - 24)

George. Listen to my tale of a dog. I shall call it "NAPOLEON's GREAT REVENGE; and to every man deeply injured and unjustly treated, I would say, "Go thou and do likewise."

The American brig "Cecilia," Captain Symmes, on one of her voyages, had on board a splendid Newfoundland dog, named Napoleon. He belonged to one of the crew named Lancaster. Captain Symmes, however, was not partial to animals of any kind, and had an unaccountable repugnance to dogs. This dislike he one day manifested in a shocking manner; for Napoleon having entered his room, and by wagging his great tail, knocked paper and ink off his desk, the captain seized a knife, and cruelly cut the poor animal's tail off. The dog's yell brought his master to the spot, and seeing the calamity and the author of it, without a moment's hesitation, he felled Captain Symmes to the cabin-floor. Lancaster was put in irons, from which, however, he was soon released. Captain Symmes repented his cruel deed on learning that Napoleon had once saved his owner's life.

But a few days elapsed ere poor Napoleon became the hero of a more thrilling occurrence, the very thought of which has often filed me with horror. During the interval the noble beast was not at all backward in exhibiting his wrath at the captain by his growls, whenever he approached. In vain did his master, fearful for the life of his dog, essay to check these signs of his anger. Captain Symmes, however, made due allowance and offered no further harm to him. One morning, as the Captain was standing on the bowsprit, he lost his footing and fell overboard, the "Cecilia" then running at about fifteen knots.

"Captain Symmes overboard!" was the cry, and all rushed to get out the boat as they saw a swimmer striking out for the brig, which was at once rounded-to. By the time the boat touched the water, their worst fears were realized; for, at some distance behind the swimmer, they beheld, advancing towards him, the fish most dreaded in those waters — a large white shark.

"Hurry! hurry,'men, or we shall be too late!" exclaimed the mate. "What's that?" The splash which caused this inquiry was occasioned by the plunge of Napoleon into the sea. The noble animal rapidly made his way toward the now nearly-exhausted captain, who, aware of his double danger, and being but a passable swimmer, made fainter and fainter strokes, while his adversary closed rapidly upon him.

"Pull, boys, for dear life," was the shout of the mate as the boat now followed the dog.

Slowly the fatigued swimmer made his way; ever and anon his head sank in the waves, and behind him the noise of the voracious animal told him what fearful progress he was making, while Lancaster, in the bow of the boat, stood with a knife in his upraised hand, watching alternately the captain and his pursuer, and the faithful animal which had saved his own life.

There was a fixed look of determination in Lancaster's face, which convinced all, that should the dog become a sacrifice to the shark, Lancaster would revenge his death, if possible, even at the risk of his own life.

"What a swimmer!" exclaimed the men who marked the speed of the animal. "The shark will have one or both, if we don't do our best." The scene was of short duration. Ere the boat could overtake the dog, the enormous shark had arrived within three oars' length of the captain, and suddenly turned over on his back, preparatory to darting on the sinking man and receiving him in his vast jaws, which now displayed their long, triangular teeth.

The wild shriek of the captain announced that the crisis had come. But now Napoleon, seemingly inspired with increased strength, had also arrived, and with a fierce howl leapt upon the gleaming belly of the shark, and buried his teeth in the monster's flesh, while the boat swiftly neared them.

"Saved! if we are half as smart as that dog is!" cried the mate, as all saw the voracious monster shudder in the sea, and quivering with pain, turn over again, the dog retaining his hold and becoming submerged in the water. At this juncture the boat arrived, and Lancaster, with his knife in his teeth, plunged into the water where the captain also had now sunk from view.

But a few moments elapsed ere the dog rose to the surface, and soon after Lancaster, bearing the insensible form of the captain.

"Pull them in and give them a bar," cried the mate, "for that fellow is preparing for another launch." His orders were obeyed, and the second onset of the monster was foiled byithe mate splashing water in his eyes. He came again, but a few seconds too late to snap up the captain's body, which was just drawn into the boat.

Foiled the second time, the shark plunged, and was seen no more, but left a track of blood on the surface of the water, a token of the severity of the dog's wound. The boat was now pulled towards the brig, and not many hours elapsed before the captain was on deck again, very feeble, but able to appreciate the services of brave Napoleon, and most bitterly to lament the cruel act which had mutilated him for ever. "I would give my right arm!" he exclaimed, as he patted the Newfoundland who stood by his side, "if I could only repair the injury I have done that splendid fellow. Lancaster, you are now avenged, and so is he, and a most Christian vengeance it is, though it will be a source of grief to me as long as I live." (25 - 28)

Mary. I have collected a few stories of dogs begging pennies, and going to the nearest bakers' shops, to get cakes or purchase buns.

There is a large black-and-white Newfoundland Dog, belonging to one of the hotels on the port at Boulogne, and, as you walk along the Quay, he will come up to you, and thrusting his nose into your hand, ask you as plain as he can, in dog language, to give him a sou (French halfpenny); if he succeeds in obtaining one, he carries it in his mouth to the barmaid, and follows her about wagging his tail till he makes her understand that he wishes to buy a biscuit. As soon as she fetches him one, he drops the copper at her feet, and returns to you before he eats the biscuit, to show you that he has made proper use of your money. As the port is a favourite walk, he gets a good many biscuits in the course of the day. He does not forget those that have once befriended him, and he takes good care that they shall not forget him.

Don't you remember, papa, the last time we were at Boulogne, we saw him?

Papa. Yes, my dear, I remember. (51)

The next anecdote:

Mary. Mr. Jno. Knight says: "As I was passing through Barnsbury one fine morning, I met some happy-faced boys with their books and slates, evidently on their way to school. They were merrily jumping along, when suddenly a large Newfoundland dog came running out of a gateway, and barking at them. Perhaps the dog thought that the boys were making too much noise — I think the boys did, for they all ran off terribly affrighted, save one little fellow. He stood quite still, and commenced patting the dog, saying, 'Please, it wasn't me.' The dog seemed to understand what was said, for he began to wag his tail, and immediately he and the little boy were on the most friendly terms."

Mr. Jesse, in his interesting book on dogs, says: — "Those who resided at Windsor a few years ago, must have seen a fine Newfoundland dog, called Baby, reposing occasionally in front of the White Hart Hotel. Baby was a general favourite, and he deserved to be so, for he was mild in his disposition, brave as a lion, and very sensible. When he was thirsty, and could not procure water at the pump, he has frequently been seen to go to the stable, fetch an empty bucket, and stand at the pump till some one came for water. He then, by wagging his tail and expressive looks, made his want known, and had his bucket filled." (53 - 54)

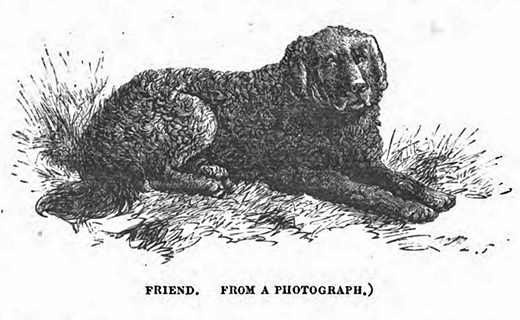

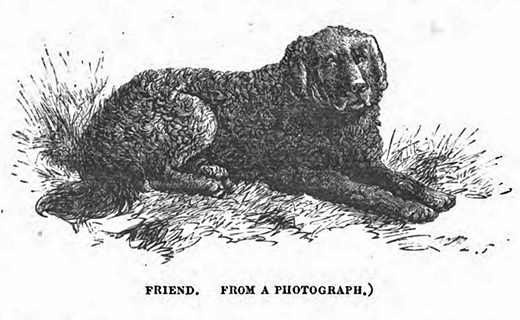

The following image appears at the end of the above anecdote, and appears to be a slightly modified version of the Newfoundland image by Weir that is used in George Pardon's Dogs: Their Sagacity, Instinct, and Uses (1857).

The next "conversation" in this book begins with another Newf-related anecdote and Newf image:

Charlotte. In the village of Harbury, Warwickshire, there exists a noble specimen of the Newfoundland dog, rejoicing in the name of Friend, and belonging to the vicar, the Rev. W. Wight. It is no uncommon thing to see Friend trudging along to the vicar's garden, with a large basket in his mouth, going for some fruit or vegetables; or trotting off in the early morning with the milk-can to a neighbouring farmer's to fetch the milk. But his useful propen sities are more than equalled by his playful ones, and his amusing antics when having a romp with the vicar's school-children must be seen to be thoroughly appreciated. Mr. R. Mimpriss, the promoter of the Graduated System of Simultaneous Instruction in the Gospel History, occasionally visits Friend's master, when a treat is usually given to the school-children, and the proceedings terminated by a general scramble. It is on these occasions that Friend becomes more than ever a "schoolfellow," watching with intense eagerness the hand that throws the fruit, nuts, sweetmeats, and cakes; and darting in amongst the children after them, with the utmost good humour, never showing the least violence to the many youngsters who fall upon him in the struggle, but always securing his share, which he brings out and devours with the greatest relish, be the eatables hot or cold, sweet or sour. Another favourite game of Friend's, is a trial of his strength with the girls, a number of whom hold the ends of a rope, while Friend seizes the middle with his teeth, both parties pulling opposite ways. With all kinds of "ball-play" he is delighted, especially the game of "bat-trap and ball." In this game he has been known to watch the batter, take his place among the catchers, and actually succeed in securing several of the balls in his mouth at once, playfully resisting all attempts of the children to remove them. In this game, as in many others, his good temper sets an example to many of his playmates, while his gentle disposition procures for him many a friendly pat. (55 - 56)

The next Newfoundland anecdote does not specifically identify the breed of the dog, but.... In the first place, the dog is named "Carlo," a popular 19th-Century name for Newfoundlands owing to the popularity of Francis Reynolds' 1803 play The Caravan, which featured a Newf by that name. Additionally, this anecdote was supposed to be illustrated by another Harrison Weir illustration of a Newfoundland holding a brush in his mouth and entitled "The Dog that Ran Away with the Brushes." This same illustration was later modified by Weir and republished twice in the 19th Century before Weir painted a watercolor version of the same image, entitled simply "Newfoundland." (For more on this image and its history, go to this page at The Cultured Newf or click the image at right.) But even though the "List of Illustrations" at the beginning of this volume lists "The Dog that Ran Away with the Brushes" on page 60, what we have on page 60 are in fact these two Newf anecdotes:

Mary. A gentleman in York had a noble dog, which was not only expert in fetching sticks out of the river Ouse and the Foss, but had been taught by his master to fetch articles from shops, etc. Sometimes the gentleman would purchase an article and leave it on the counter, at the same moment calling the dog's attention to it. On leaving the shop, he would proceed perhaps a quarter of a mile away, and then give the order, "Go back, Carlo, and fetch that parcel." Away went Carlo, and in a few minutes the noble animal would return with the purchase. Like a faithful servant, he never loitered, but ran all the way. One day the dog presented a laughable spectacle. The owner went into a brushmaker's shop, and bought a dusting-brush. It was pointed out to Carlo as usual. Unfortunately for the brushmaker, he did not cut the string which tied the brush to a number of others. When Carlo darted into the shop and seized his master's purchase, he dragged a bundle of about a dozen brushes into the street. Out rushed the brushmaker; but, on attempting to seize the bundle, Carlo gave him to understand that he thought they were paid for. Away went dog and brushes along the streets of York; and Carlo never stopped until he laid the treasure at the feet of his astonished master. It was not until the master interfered that Carlo would surrender. It was impossible to keep from laughing at the comical sight of Carlo dragging along the brushes, and the unfortunate shopkeeper running after his stolen goods.

In the town of Honiton, in Devonshire, a fine Newfoundland dog (named Lion), belonging to the Golden Lion Inn, used quietly to spend hours every day at the entrance of the house. There passed by, several times in the day, a little barking cur that never passed without insulting Lion; after bearing the annoyance several months, apparently with perfect indifference, Lion one day rose up very deliberately, and seizing the little barker by the neck, carried him across the street, and ducked him into a pond of water. He kept him, head and tail, fairly immersed for a few seconds. Generous Lion then took him out, laid him on the kerb of the footpath, there to drain and there to repent. He then walked back with becoming dignity to his usual lounging place. (60 - 61)

The final anecdote presented by Jackson is also one that had been told many times previously:

A Newfoundland dog, kept at the ferry-house at Worcester, was famous for having, at different periods, saved three persons from drowning; and so fond was he of water, that he seemed to consider any disinclination for it in other dogs as an insult on the species. If a dog was left on the bank by his master, and, in the idea that it would be obliged to follow the boat across the river, which is but narrow, stood yelping at the bottom of the steps, unwilling to take the water, the Newfoundland veteran would go down to him, and with a satirical growl take him by the back of the neck and throw him into the stream. (63)